This post is part of our symposium on the political economy of sex work. Read the rest of the symposium here.

The constant assertion that sex work was “just like any other job,” that it was experientially rewarding, richly enumerating, or spiritually significant, or that sex workers “weren’t all homeless junkies working the streets” naturally alienated those who hated their work, struggled to make ends meet, used drugs, or were homeless. A dominating narrative of empowerment also contributes to a growing stigma against sex workers whose experience isn’t strictly empowering.

— From the Introduction to $PREAD: The Best of the Magazine That Illuminated the Sex Industry and Started a Media Revolution

I was asked to address whether and how feminist and queer movements at times create a false distinction between the “agency/empowerment” of sex work and the “oppression/coercion” of sex trafficking. I am a poor Black proheaux womanist creative and erotic laborer. These locations and more are important in my analysis, so I’ll begin my answer with my own story.

I started stripping at eighteen. I knew I was going to strip long before I did it. I had become enamored with Black feminist “hoe is life” empowerment rhetoric just before college. I skipped a grade and landed at a college in southern Indiana at age 17, a vocal major at the time. “Hoe is life” is the Black woman’s answer to the slut-chic culture that swept mainstream hegemonic feminism during the second and/or third wave — our pro-hoe, full of wanna-be (or actual) sugar babies and newly minted financial dommes, and “marry up” (into wealth and usually out of blackness) feminists. As a bisexual woman who had been exploring her sexuality throughout childhood, with girls first and boys later, I was intrigued by this idea that I felt fit my omnisexual proclivities. I was eager to dabble in promiscuity and discover erotic pleasure, and my entrance into the idea of erotic labor was part of that.

The other part: money. The first time I dipped my toes into erotic labor, it was for pocket money. Young men asked and offered. They were in my age group, so I didn’t feel exploited, and I wasn’t. I was in college, and for many young Black women, college is where we find ourselves. The need seems urgent — many of us grew up in church or similarly constrained by our families. Black and brown women of certain cultures are considered naturally promiscuous in the wider dominant white culture. The way we dress, how quickly we develop, all of it is scrutinized. I was called everything from a dyke to a whore growing up as adults rushed to categorize my known experiences: too (physically) close to this or that girl, too flirtatious with such and such boy, the way I licked an ice cream. Everything I did seemed to drip with eroticism, even when I wasn’t aware. I thought, there must be power there.

Long story short: I was eighteen and out and couldn’t find a job. I quickly made the decision to dance and eventually became a sugar baby, prostitute, camgirl and phone sex operator over a period of years.

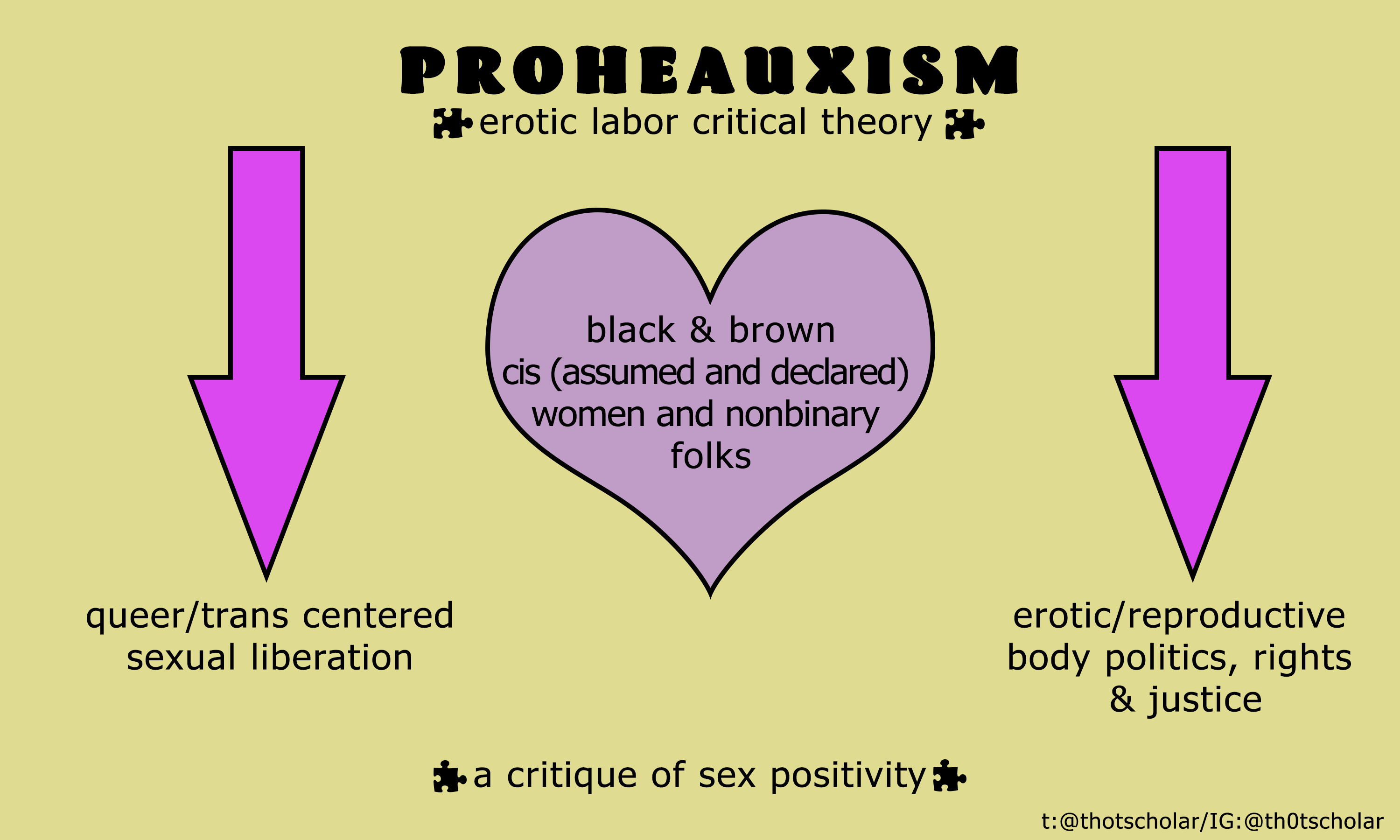

While in college I projected this facade of sexual bravado, a brazen bisexual down for anything, I knew I had moved out of “hoe is life” territory into “real hoe” territory — away from curiosity and transgressive (feminist-sanctioned) promiscuity into erotic dancing and prostitution. I later posited a theory of proheaux womanism to counter the lack of actual sex positivity I saw in Black feminism. Proheauxism is a critical theory that centers the multiply marginalized and explicitly includes sex workers.

Sex positivity, in contrast, centers “… transgressive sexual practices and styles [that] tend to promote an individualistic concept of agency, neglecting to engage with the political and economic context that most sex radicals recognize as oppressive.” (Glick). As I put it in my original definition of “proheauxism,” we need something more — “not just pro-fucking around, but pro-us. Not just sex positive, but realistic about nuance and shades of oppression. [Something that] understands the complexity of choice & empowerment when residing in a colonized body. Against all forms of racial fetishism. Against the language of slavery co-opted by mainstream [white] anti-porn “activists.’”

How does sex positivity fail to think structurally, and about political and economic context? Though feminists and queer theorists love the subversiveness of proclaiming “hoe is life,” they are also married to the idea that eventually they will be monogamous. While it is perfectly natural and okay for them to have sex with anyone they want and to extoll “safer kinky sex,” many still believe that paying for sex sullies the interaction, or removes from it any possibility of true “consent.” Many also believe that most erotic laborers are having sex with married men and are thus accomplices in cheating, which has become a major point of contention among Black feminists and Black women generally, many of whom wish to “marry up” to a faithful man and are operating out of scarcity. This relates to the idea that having sex with a lot of men (as an erotic laborer) equals having indiscriminate sex, even though it is clear that choice of clients among erotic laborers is relative (to income level). These mentalities often lead to erotic laborers being doubly denigrated. Similar to bisexual women, sex workers’ behavior is categorized as damaging to the gender at large. Both groups are viewed as complicit in cis male abuse and sexual domination of women.

“Survival sex worker” is the new term du jour to describe impoverished, homeless, and/or drug-addicted erotic laborers who don’t fall within the empowerment “hoe is life” category. One implication is that we are unsuccessful. This term highlights an emerging binary within sex work feminism (the sex worker version of sex positivity). In my paper “Defined/Definers,” I wrote:

The term survival sex worker is a wholly unnecessary term used to group together “low-end” sex workers who are not making a living wage. It is a term fraught with stigma that borders on the pejorative, especially when used by people who are not members of this class of sex workers. Indeed, [the word] “survival” evokes an image of a poor, possibly drug-addicted prostitute who most likely works on the street or out of strip clubs or Backpage mimics, and is working to make ends meet.

I have witnessed people juxtaposing survival/professional erotic labor as if these are two distinct groups. For many the point seems to be to capture the gray area between sex work and sex trafficking, but the term survival sex worker fails at this, instead promoting a dichotomous image of disempowered low-end erotic laborers who are simply ‘surviving’, and empowered high-end erotic laborers who are looked at as astute, capable businessfolk. This mirrors our culture’s feelings about poor people, as well as reinforcing the choice/coercion binary. It is implied that those who are just surviving are making poor decisions, are drug addicted, or were coerced into the work, economically or otherwise, in a way that most empowered sex workers are not.

So yes, there is a false (and neoliberal) distinction implied in the feminist distinction between the “agency/empowerment” of sex work and the “oppression/coercion” of sex trafficking. As I’ve described elsewhere, those “feminists who believe that sex work in all its forms is inherently exploitative to women … conflate sex work (a profession) and sexual violence and exploitation. Doing this obscures the very real issues with each of these — sex work and sex trafficking — and prevents anything actually being solved.” (Solving the real violence and issues requires decriminalization, as I’ve also described here.)

Sex-positive feminists often become another version of choice feminists. Despite #intersectionalfeminism sweeping mainstream feminism, erotic laborers are still outsiders in both feminist and queer theory, especially if they are “survival sex workers.” The failure of feminists and queer theorists to listen to erotic laborers calls their entire praxis into question: what is a body politic when it is not communal, when agency is stripped from poor erotic laborers who skirt the line between choice and coercion? Because that’s the real problem. Centering personal liberation and elevating the private/consumerist sphere over the public sphere will never bring us the erotic liberation we seek.

Other sources:

“Sex Positive: Feminism, Queer Theory, and the Politics of Transgression” by Elisa Glick

Defined/Definers in heauxthots: On Terminology, and Other [Un]Important Things (by suprihmbé)