This is a bonus post to our symposium on inflation. Read the rest of the symposium here.

***

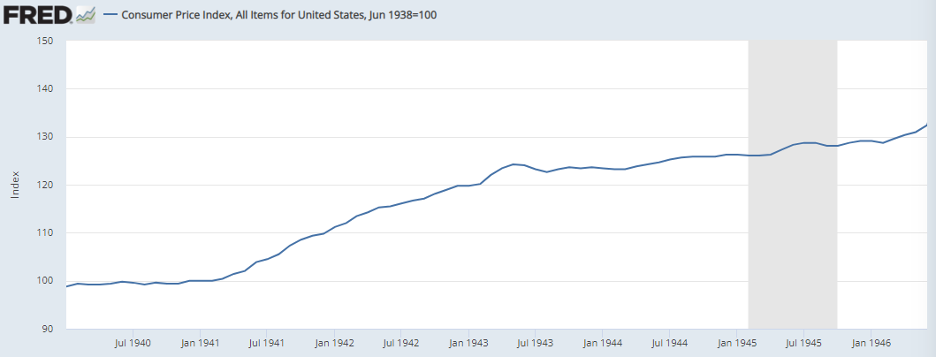

Historians and economists frequently invoke the World War II-era Office of Price Administration (OPA) as the sole exception to the general rule against price control. Under its contribution to the national mobilization program, the price level remained largely stable, with the consumption basket tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for low- and moderate-income families rising just 12 percent between May 1942, the month of the first across-the-board price freeze, and January 1946—an annualized rate of around 3.3 percent. During the five years of wartime mobilization, national output more than doubled, unemployment dipped below 2 percent, real civilian consumption increased by 50 percent, and the labor share of national income grew. Annual federal budget deficits ranged from 12.7 to 27.5 percent of GDP during these years.

The performance would not have been so impressive, however, were it not for changes to legislation authorizing the OPA program—amendments known as the Stabilization Act of October 1942. As originally crafted in the summer before Pearl Harbor, the Emergency Price Control Act (EPCA) introduced fundamental problems into the national plan that were as severe in their political consequences as those economic risks it sought to guard against. This post concerns one lesson of the World War II stabilization program: if inflation is to be avoided at levels of demand necessary to maximize employment of labor and existing productive capacity, then national planning must come to exercise influence over sector-specific programs. During the World War II stabilization program, this necessity was most evident in the conflict between the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), responsible for managing agricultural production and income, and the OPA, responsible for stabilizing prices.

For nine months after the EPCA’s passage in January 1942, the price index for working-class consumers continued to rise at a monthly rate of 0.44 percent, an annualized rate of 5.3 percent. The primary reason, debated in the Congress during these months, was the effective exemption of agricultural commodities from price control. So intolerable was this persistent rise in the cost of living driven by food that, by October, under repeated requests from the OPA and labor, and after a series of emergency addresses from the White House to the Congress and nation, the price control law was amended.

As we again confront the problem of how to manage full employment without inflation, it is today worth considering the reasons for the EPCA’s original construction to exclude raw agricultural commodities, the inadequacy of these limitations for curtailing inflation, and the program’s eventual necessary amendment. In our own time, we have witnessed the havoc competing national priorities can place on the national economy. The generations-long growth of prices in medicine and medical services is case in point, as are the competing goals of energy “independence” and developing alternative fuels. If we are to have in a much shorter period a level of demand necessary to direct rapid reconversion of our national patterns of energy consumption and production, while sustaining our commitment to full employment, we must inevitably confront this aspect of the problem of national planning, or risk the possibility of uncomfortable and politically destabilizing inflation.

Origins

Price control had been underway for eighteen months when the Japanese seaborne air force attacked Pearl Harbor. In May 1940, under a neglected but unexpired WWI law establishing a Council of National Defense, the President established an Advisory Board to the Council to serve as the nucleus of an incipient planning program. Its responsibilities included the award of military contracts, financing construction of government-owned plants, rationing industrial materials in short supply, shaping the supply of and income to labor and agriculture, and managing prices.

To oversee the Advisory Board’s Division of Price Stabilization, President Roosevelt appointed Leon Henderson, then a member of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and executive secretary of the Temporary National Economic Committee (TNEC). Without statutory power to fix ceilings, Henderson’s ad-hoc inflation control program consisted initially of the collection of statistics by commodity and by industry, estimation of supply elasticities, and the identification of foreign sources of supply jeopardized by wars abroad. Where Henderson saw the need for a price ceiling, his office consulted with industry officials, sought voluntary agreements, and, when necessary, altered priority orders in public procurement to attempt to secure participation from recalcitrant producers. To assist him in this task, Henderson recruited a young agricultural economist named John Kenneth Galbraith.

Until March 1941, stable prices prevailed. Production in many lines was still recovering from depression lows, and the large pulse of federally financed military orders would not come online until the Lend-Lease Act that month. In April, witnessing rising prices, the President issued Executive Order 8734 to strengthen Henderson’s program, establishing the Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supply (OPACS), which was authorized to “take all lawful steps necessary or appropriate” to prevent “price spiraling, rising costs of living, profiteering, and inflation”—including, in addition to its existing practice of publishing as voluntary guidelines official price schedules, powers to purchase and distribute commodities.

Yet inflation continued to accelerate after EO 8734. As early as February 1941, OPACS general counsel David Ginsburg and Harold Leventhal had drafted a statute on the basis of the ongoing, non-statutory program, and began circulating the language among the staff. By summer 1941, as the need for greater statutory powers in the face of inflation became increasingly apparent, the President sent a message requesting legislation to the Congress, where hearings began in the House Banking and Currency Committee on August 5.

The Problem of Economics: Farm Prices and Non-Farm Prices

Presented to the Congress, the Ginsburg-Leventhal statute promptly encountered the organized influence of executives and lobbyists seeking exemptions from the federal efforts to regulate their industries’ income. Among the most powerful of these groups was the American Farm Bureau Federation, whose leadership was then torn between small farmers and an alliance of wealthy Midwest grain farmers and the cotton planters of the Jim Crow South. Among their most powerful representatives was Henry Steagall of Alabama, chairman of the Banking and Currency Committee.

To explain the program to the power brokers and ensure Congressional passage, Henderson, Galbraith and Ginsburg rode to the Hill to meet with Steagall before the hearings began in the House. Steagall insisted the ceiling on agricultural prices be set at 110 percent of USDA price targets. Known as “parity prices,” such price targets had unified organized agriculture’s diverse base since the collapse in farm prices that followed WWI. They were named to represent the same relationship between the prices of raw-agricultural commodities (“prices received”) and the prices of non-farm commodities (“prices paid”) in the base period of 1909-1915, the period before war and depression had distorted their ostensibly normal relationship.

The New Deal wrote parity prices into law. They were the foundational objective of the USDA’s supply management program, which was designed to raise farm prices to parity rates through acreage restrictions, plantings secured through so-called “non-recourse loans,” and government stockpiles of surplus commodities. Whenever prices fell below USDA targets, usually 85 percent of parity, farmers who had received USDA loans to finance planting confronting lower commodity prices defaulted on their obligations and surrendered their product to USDA—which took them as collateral in place of any other recourse. A farmer’s income was thus protected by prices guaranteed in the terms of their loans, always at some high percentage of parity.

As prices rose during the war boom that began in 1939, farm prices were only then returning to pre-Depression levels. Corn, for instance, which was selling at 40 cents a bushel in November 1938, was selling at 64 cents a bushel in November 1941.

Representative Steagall’s insistence on statutory language holding OPA ceilings over agriculture to 110 percent of parity promised to allow farm, and hence food, prices to continue rising after the introduction of mandatory controls. As Galbraith remembered, “We had accepted that we could not set the prices of farm products below parity,” but “Steagall’s proposal [of 110 percent of parity] effectively exempted them all and thus all living costs from control.” Meeting with Steagall, Henderson relented and accepted the 110 percent rule for raw agricultural commodities. Ginsburg and Galbraith, the latter wrote, “were appalled.” Returning to the office, Galbraith pressed the matter with Henderson, who, defensive against a concession whose consequences he was only then realizing, “reacted with volcanic force, stopped the cab and invited me out.”

Despite this concession, the farm lobby delayed passage of the EPCA until after Pearl Harbor. Congressional controversy during the summer and fall of 1941 focused not only on the powers the President requested to fix price ceilings, but also to license producers, and impose treble damages for violations. Most divisive to Congress was the power for the government to enter the market as a purchaser and distributor of commodities. “To make ceiling prices effective,” Roosevelt had explained in his message to Congress, “it will often be necessary, among other things, for the Government to increase the available supply of a commodity by purchases in this country or abroad. In other cases it will be essential to stabilize the market by buying and selling as the exigencies of price may require.” This power was of particular concern to the farm lobby: the volume of agricultural commodities in government storehouses, swollen from years of low prices, might be used under the new law to satisfy consumer demands and thus potentially to depress high farm prices.

The final Act passed January 30, 1942. Section 2(a) declared that the Administrator “may…establish such maximum price or maximum prices as in his judgement will be generally fair and equitable and will effectuate the purposes of this Act.” The Administrator was obligated to “make adjustments for such relevant factors as he may determine and deem to be of general applicability, including the following: Speculative fluctuations, general increases or decreases in costs of production, distribution, and transportation, and general increases or decreases in profits earned by sellers of the commodity or commodities…” Thus, a plenary power was granted to regulate the distribution of income, through the price system, across the industries of the American economy. The only problem, as the OPA officials already foresaw, was the exemption of raw agricultural goods.

The Problem of Politics

For nine months under the act, the nation discovered the impossibility of both guaranteeing farm incomes above parity prices and stabilizing the cost-of-living. Since raw agricultural commodities were a basic input for labor in the form of food, allowing food prices to surpass other prices threatened to raise labor costs and thus the entire parity level—undermining the entire program. In late April 1942, invoking his new statutory powers, Administrator Henderson issued the General Maximum Price Order, the first attempted comprehensive freeze of all prices during the war. General Max arrived the day after the President announced a 7-point stabilization program, including the request for legislation to lower farm-price ceilings. In the first three months after the arrival of General Max, farm prices rose 7.2 percent. In total, the CPI would rise 3.3 percent, or an annualized rate of more than 6 percent, in the period between the freeze and the Stabilization Act of October 1942.

The exemption of agricultural prices built a wage-price spiral into the defense effort. As farm prices rose outside of OPA control, so too did food prices. This intensified the pressure among the militant and organized labor movement for wage increases. In the nation’s industrial centers, the failure to control the increase in the cost of living undermined the authority of many cooperative union leaders, led to the disintegration of their locals, dramatically raised turnover in the factories, and generally interrupted production.

In response, on September 7, 1942, Labor Day, the President once again sent a message to congress requesting amendments to the Emergency Price Control Act. Delay on farm prices, Roosevelt wrote, “has now reached the point of danger to our whole economy.” That night, the President broadcast nationally in his fireside chat the need to bring down farm price ceilings. “Last January,” Roosevelt said, “the Congress passed a law forbidding ceilings on farm prices below 110 percent of parity on some commodities…. This act of favoritism for one particular group in the community increased the cost of food to everybody… But it is obvious to all of us that if the cost of food continues to go up, as it is doing at present, the wage earner, particularly in the lower brackets, will have a right to an increase in his wages.” The President was requesting greater control of farm prices, he explained, to avoid this “threat of economic chaos.”

For the next four weeks the House and Senate simultaneously debated concessions to the farm lobby in exchange for lowering farm price ceilings. The final agreement, passed in the House on September 30 and the Senate October 2, raised the minimum government payment in commodity loans to farmers to 90 percent of parity prices. Thus, as farm price ceilings were lowered, so too was income guaranteed to farmers raised.

Incomes Policies and the Politics of Stabilization

The October 1942 Stabilization Act amendments to the Emergency Price Control Act laid a statutory basis for the basic apparatus of wartime stabilization policy in price control, rationing, and government purchase and distribution of commodities. Historians have generally neglected the importance of the October 1942 law in the stabilization program. Hugh Rockoff, for example, considers the twelve-month period after the General Max, and notes the 7.5 percent inflation as a measure of the government’s success in stabilizing prices. However, the program should more accurately be understood as two distinct periods, demarcated by the Stabilization Act and the “Hold-the-Line” Order invoking its authority in late April 1943. Though the cost of living rose 16 percent during World War II, from May 1943 to January 1946 it rose just 3.9 percent—an annualized rate of 1.4 percent. The timing of this demarcation depended not only the decision to impose a second freeze, but on the deliberations required by the legislative process necessary to give the power of law to executive action.

Though some powerful labor leaders would continue to press for greater income claims, an essential agreement was forged in concessions from the farm lobby that would hold until victory in Europe and Japan reopened debate over national economic policy.

By the late 1960s, the necessity of restraining sectoral income claims within the constraints of real national output had become widely known among economists. Then, experts discussed solutions in terms of “incomes policies.” When national economic programs place competing demands on the nation’s resources, they understood, political decisions must be made over the distribution of real income available at full employment. Such incomes policies were once seen as a necessary supplement a fiscal-monetary growth program, and during the Cold War the North Atlantic capitalist governments realized that controlling incomes through limitations on private management and business decisions was necessary to achieve macroeconomic goals.

The political struggle over income during World War II was complex, involving both high marginal income tax rates on corporations and individuals, as well as new taxes on profits in excess of a pre-war base period. But in essence the political competition during the war was between the organized farm lobby and organized industrial workers over the price of food. (Manufacturing and energy corporations, who secured profits through cost-plus contracts and rebates written into the excess profits tax law, would enter the fray during 1946.) During WWII, no theory of fiscal-monetary management had yet become cannon, much less any idea of “incomes policies” to supplement it. Nevertheless, the mature New Deal, augmented by wartime emergency powers, discovered the same problems and groped its way toward political solutions in the modern search for stability. The same struggle for consensual self-government bedeviled the managed economies bequeathed by the war. In new configurations, we confront it today.