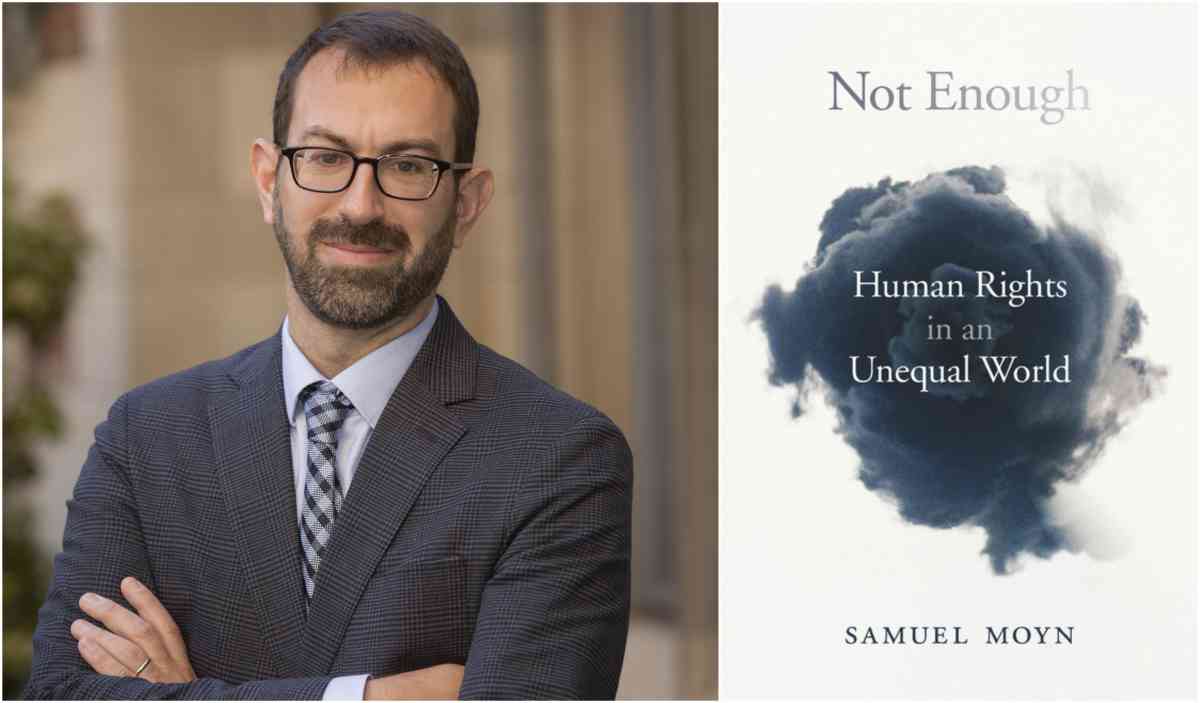

Did the Human Rights movement fail? In his new book, Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World, Samuel Moyn responds in the affirmative. He argues that the international human rights movement narrowed its agenda to address the sufficiency of minimal provision, leaving the movement impotent in the face of rising global inequality and attacks on social citizenship at the level of the nation-state. Without indicting the movement for the rise of neoliberalism, he nevertheless highlights the historical coincidence of international human rights and “the very economic phenomena that have led to the rise of radical populism and nationalism today.”

The question of how we got here, and which legal tools might beat back the current crisis in international human rights, animates our first LPE Blog discussion series. Encouraged by many requests from readers, we’re working to develop a more transnational conversation on the blog, as well as more sustained debates and discussions of key issues. The series kicks off today with an introductory piece by Sam Moyn, and will be followed by responses to Not Enough from historians, political theorists, legal scholars, and human rights activists.

I decided to take another stab at writing a new history of human rights ideals and movements, because a few critics persuaded me that I had left the all-important context of political economy out in my first try.

Now that Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World is out, it is worth explaining how I proceeded — not to forestall new rounds of criticism, but to help make sure the rise of human rights law in our time is part of the broader venture in law and political economy that colleagues and friends have launched on this fantastic blog.

The deepest question the broader venture of this blog raises — like the narrow venture my book pursues — is how best to think of law in relation to political economy. How precisely does law help organize the social world, and as what kind of causal driver or constitutive feature in comparison with others? The question matters not merely for the sake of better understanding but also, for those who care, to locate plausible levers of change. And law, of course, is just one example of something to theorize in relation to political economy. At stake in my own attempt is a history of ideals and movements, too, but they all require a theory explaining their place in the making and unmaking of social orders.

Contemporary Marxists, such as our opposite numbers on the equally new blog Legal Form, are pressing such questions too. Nonetheless, their insights into the need to relate law to its larger constitutive and causal settings have not saved them from a bitter debate about the meanings of human rights in bringing about or even buttressing an unjust social order, or how they might emancipate people from it. Recent essays by Jessica Whyte and Paul O’Connell (who will be contributing to this symposium) suggest as much. Surprisingly, even Marxists, heirs to a traditional critique of rights in the name of unmasking the depredations of political economy, are not sure whether to deflate or inflate norms of individual entitlement which have again surged as the moral lingua franca of the day, as they did in Karl Marx’s own.

Not Enough tells a story that insists on the ideological flexibility of rights — up to a point. Karl Marx faced a nineteenth century political economy in which rights were so profoundly indentured to unjust outcomes that even liberals who had their own social democratic and socialist legacy — or at least a New Deal one in our country — ended up spending decades demystifying rights. The last time the American legal academy took political economy seriously as a problem, it was among progressives like Robert Hale and Karl Llewellyn whose central goal was to provide analytical tools to lift the political obstacles that impeded the attempt to reform the unjust political economy Marx denounced. In Continental Europe and around the world the critique of rights went much further, including in more liberal circles, than ever occurred in the United States.

One result, recorded in Not Enough, was the creation of a new conception of social rights that would not have been intelligible within earlier political economy or in Marxist responses to it. (Before then, Americans sometimes used the concept of social rights to refer to interpersonal association that it was not up to the state to protect, most notably for African-Americans under Reconstruction amendments.) The twentieth-century innovation in rights theory that pioneered beyond nineteenth-century understandings was yoked to a broader defense of a more egalitarian form of political economy that came increasingly to the fore under all forms of transatlantic regime, as the founders of comparative constitutionalism noticed. All deeply exclusionary in many respects, but inaugurating a new direction in political economy, welfare states showed that rights could transform their meaning in a new ecology. Not Enough argues that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), which was later reclaimed for a supranational project of stigma, is best interpreted as an international template for the nationalist projects that welfare states represented — with these states themselves clustered in global space in the North Atlantic in an era of continuing empire.

For all its flaws, the welfare state had more appeal to more people than any political economy before. The middle of Not Enough goes on to chart the attempted globalization of the new “social” state in the aftermath of empire, once the hundreds of millions still its subjects in the 1940s got free. Starting with their attempt to reproduce welfare political economy (in the era of well-known debates over import substitution and other strategies), I interpret the agenda of the postcolonial states as ultimately bordering on a scalar project that raised egalitarian concerns to global dimensions — something prior Marxists and socialists had never really done. At best, in a treaty like the International Covenant for Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (adopted into 1966 and entered into force in 1976), decolonized states could rely on rights, as they had done in their constitutions, to endorse the importance of sufficient provision of the good things in life. But it was a commitment which came nowhere near exhausting their ambitions either in substance or scale. Global egalitarianism was their most novel contribution to the political imagination of humanity, even if it mostly remains only to stoke our bad conscience that where people are born is still the most determinative fact about them (or to inform neoliberal apologetics that modest global improvements in equality offset catastrophic local declines in it).

Then “neoliberalism” came, an event with immense consequences both for the welfare state and its prospective globalization. Among the many distinctive features of the neoliberal version of globalization of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries was its comparative toleration of antipoverty norms, as the history of the World Bank shows in particular. An ethic of “basic needs” that castigated the developmentalism of postcolonial states surged in the face of their own globally egalitarian project. And the explosion of international human rights politics in the same era came to parallel these priorities. In the end, it was neoliberalism itself – in the form of Chinese marketization – that may have served the global poor most in fact. But in belatedly giving more and more emphasis to economic and social rights, human rights movements longed to pitch in, especially once the Cold War ended. They raised their voices against the World Bank and other international financial institutions that refused to frame their own concessions to antipoverty initiatives in rights terms. But they lost any ethical communion with the egalitarian purposes the transatlantic national welfare states had maintained, and that postcolonial leaders had aspired to globalize.

The story is replete with irony. The human rights revolution retrieved the Universal Declaration from obscurity, but cut it off from its egalitarian ambiance, as the socialization of rights that welfare political economy had allowed in modular nations only survived in the truncated and wizened form of demands everywhere for sufficient provision alone. And instead of breathing the atmosphere of political majorities and state capacitation, with socialist parties and trade unions as their agents, rights were broadly reimagined as part of the ethical correction of the ascendancy of the rich, implemented for the sake of unpopular minorities by state critics, in shifting coalitions with the newer but weaker tools of informational shaming and legal resistance.

If persuasive, this account suggests that rights are flexible, functioning very differently depending on the larger political economy that hosts them. And if so, it means they are hardly condemned in either theory or practice to the politics they have helped incarnate in our time — one in which the worst off, though still outrageously miserable, are better off than ever, while the rich reap the lion’s share of gains in most nations. I do not think, therefore, that the totalistic critique of rights that has featured in critical traditions since that of Marx himself is plausible (however essential some of those traditions are to anyone interested in restoring needed attention to political economy). But it also means, for our generation of reformers, that rights have to be saved from their own variability.

I welcome the discussion of Not Enough on this blog — and even more our ongoing attempt to think creatively about how to place law, with the moral ideals it embodies and the social movements that advance those ideals, in the setting of our increasing sensitivity to the indispensable theme of who gets what.