The global food system is in crisis for the third time in fifteen years. Food prices are hitting all-time highs, pushing hundreds of millions of people deeper into poverty and food insecurity and threatening political stability in regions around the world. The World Food Programme has called the current situation a “hunger catastrophe,” noting that since 2019, the number of people facing acute food insecurity has soared from 135 million to 345 million and that almost 50 million people are currently facing emergency levels of hunger. All of this on top of the brutal fact that more than 800 million people go to bed hungry every night, a number that has been steadily rising for the last seven years.

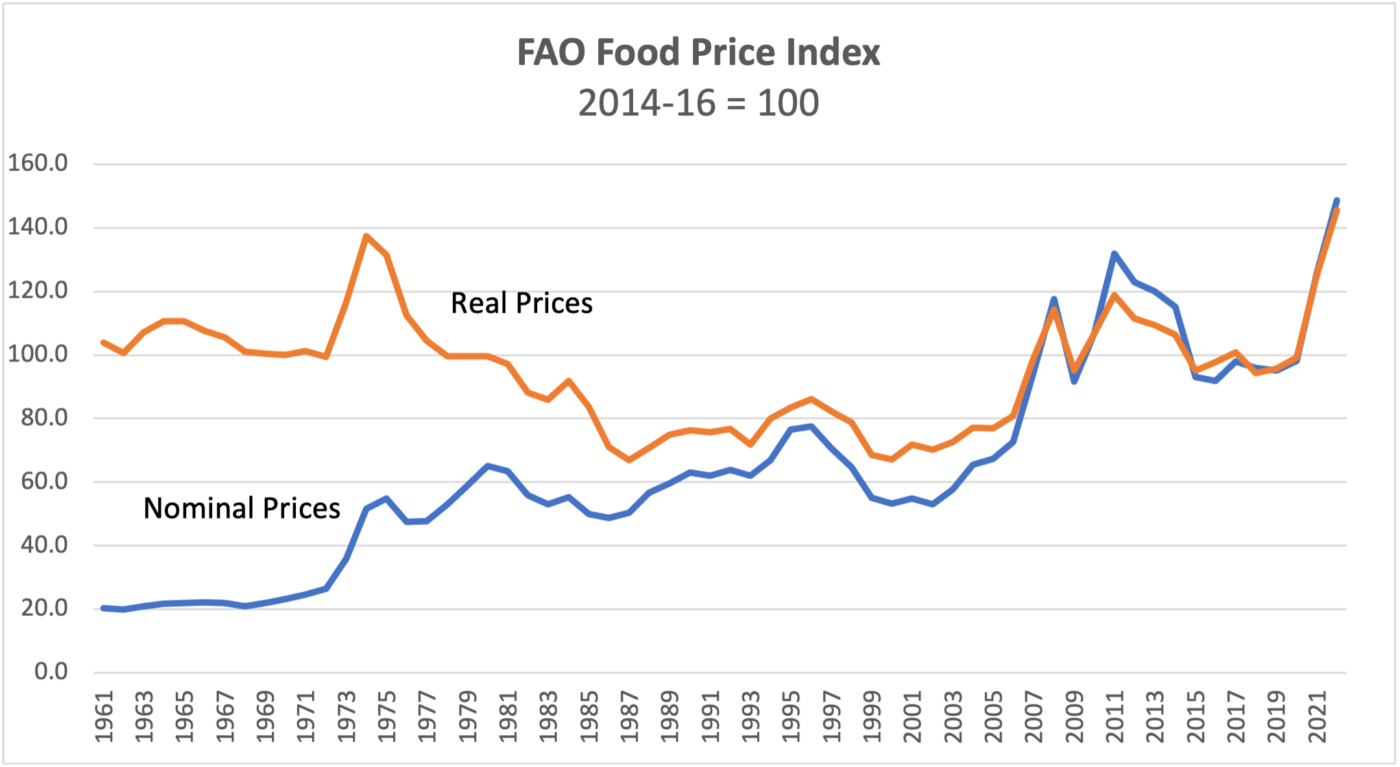

According to FAO’s Global Food Price Index, food prices are higher in real terms than the previous record set in the early 1970s when a combination of oil price shocks, inflation, and the Soviet Union’s secret purchases of some three quarters of the world’s commercially traded grain (the so-called Great Grain Robbery) drove prices sharply higher and led to widespread hunger and famine.

To be sure, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been the main trigger for the recent price spikes and extreme turmoil in the markets. Ukraine and Russia together account for more than a quarter of the world’s wheat exports and a substantial share of other key crops such as corn, not to mention key raw materials and natural gas that are critical inputs for fertilizer (fertilizer prices have also moved sharply higher over the last several months). If anything, Putin has reminded the world of the power of grain in geopolitics, providing a contemporary example of Lenin’s famous observation that “grain is the currency of currencies.”

But the current crisis goes much deeper than the disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine. And the consequences may last far longer.

Price Shocks, Political Stability, and Food Protectionism

For starters, food price shocks are a political nightmare for weak governments. Food protests and “food riots” almost always accompany severe price shocks, serving as potent reminders of the deep moral economy of food as a basic system of provisioning. During the global food crisis of 2010, to take one recent example, widespread protests over the price of bread and food in several North African countries contributed to the instability and rage that fueled the Arab Spring.

In the current crisis, governments are already taking action to mitigate the political fallout from high prices, adopting various protectionist measures to secure domestic food supplies and placate increasingly restless publics. In April, for instance, the Government of Indonesia banned exports of palm oil, the most widely consumed edible oil in the world, in an attempt to promote national food sovereignty across the archipelago and bolster President Jokowi’s sagging popularity. While it is too early to assess the overall political impacts of Indonesia’s export ban, the decision sent shocks waves through global vegetable oils markets, as Indonesia accounts for almost 60% of global palm oil exports.

A few weeks later, the Government of India, reeling from an epic heat wave that scorched parts of the country’s wheat belt, announced that it was banning the export of wheat from the country, sending global wheat prices to new highs. India’s announcement was particularly concerning, given that many analysts had expected India (the world’s second largest wheat producer after China and eighth largest exporter) to help fill the gap in wheat exports created by the war in Ukraine.

Experts contend that by limiting trade these protectionist measures will only make the global food crisis worse—further disrupting the ability to move supplies around the world and making life that much harder for those countries and their populations that depend upon food imports. For governments facing immediate domestic political imperatives to act against soaring food prices, however, liberal trade theory offers cold comfort. While the longer-term political implications of these developments are impossible to predict, they underscore persistent questions about the future of globalization in the face of rising nationalist sentiments, the growing scramble for resources, and various forms of illiberal and authoritarian populism.

Merchants of Grain

One thing the current crisis has made clear (yet again) is that prices are not simply signals but also relationships, and that those relationships can be coercive. It has also highlighted the importance of attending to how prices are made and who sets the rules for price making in particular markets. The extreme volatility and high prices in the markets for major global agricultural commodities are, in this view, not simply a reflection of supply and demand but also a product of the specific ways of price making in these markets. For example, early evidence suggests that large traders and speculators have been quite active over the past several months, leading some to argue that excessive speculation in the commodities markets may be exacerbating food price shocks, just as it did during the 2010 food crisis.

More directly, the large (and mostly privately held) grain trading companies, including especially the big four (Archer-Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Dreyfus, known collectively as the ABCDs) are also well-positioned to make substantial profits as the world grain trade adjusts to the war in Ukraine and the ongoing volatility in global markets. While these companies have long sought to stay out of the public eye, their role in the global agro-food system is fundamental (see, e.g., Dan Morgan’s epic 1979 Merchants of Grain on their role during the food crisis of the 1970s). One report estimated that between 70 and 90% of the global grain trade is controlled by these four companies. All of these companies have stayed in Russia and will play a critical role in getting Russian wheat and other commodities to market in the months ahead.

If the past is any guide, the current price shocks and disruptions will likely lead to investigations of agricultural commodities markets, the trading relationships that structure those markets, and the supply chains that move food around the world. Questions have also been raised about the lack of domestic food security in many countries and the adequacy of current relief capacities. Rich countries have responded with modest pledges to do more, offering an additional $4.5 billion in emergency food aid at the recent G7 summit in Germany—an amount that falls far short of what the World Food Programme and Oxfam say is needed to prevent millions from starving.

The deeper question in all of this is whether the current crisis will lead to meaningful reforms so that the world will be better prepared for the next crisis—a question that requires more systematic engagement with the structural features of the global agro-food system.

Food Crises and the Deep Structure of the Global Agro-Food System

Much of the mainstream response to the current food crisis has focused on the mismatch between supply and demand. The solutions that emerge from this line of thinking typically involve better, smarter, more productive agricultural systems, often framed against a stark Neo-Malthusian backdrop of feeding a future world of 9 billion people. Simply put, people are hungry (and will go hungry in the future) because the world is not producing enough food as efficiently as it could.

But decades of research have made clear that famines and food crises stem not from a lack of food, but from lack of access. Put another way, widespread hunger is not a technical problem that stems from insufficient production; rather, it is a political economic problem that stems from inability to pay for or otherwise acquire food (an entitlement failure, to use Amartya Sen’s term). As numerous analysts have pointed out, even with the war in Ukraine, the world has sufficient stocks of wheat and other crops to meet global demand. While crop failures, supply disruptions, and ongoing conflicts are clearly hampering the ability to deliver food where and when it is needed, the bigger problem is that prices for food are too high for an increasingly large number of people across the globe.

In short, it is the underlying political economy of the global agro-food system that has created the conditions where hundreds of millions of people don’t get enough to eat. Law and legal arrangements have been central in creating this political economy, operating not simply as a set of constraints on economic actors (through rules and regulations) but also as a constitutive force creating assets, structuring economic relationships, and shaping the distributional struggles around land, food, and other necessities. This happens at two levels: the macro-level structuring mechanisms of the last half century (namely, international trade law, foreign investment law, and debt and structural adjustment) that have pushed and pulled countries in the Global South into a situation of dependency on food imports and worked to discipline and constrain public systems of provisioning, and the micro-level legal techniques (namely, contract, property, and corporate law) used by foreign and domestic elites to dispossess and displace smallholders and further integrate land and farming into commercial structures and transnational value chains. And all of this is now unfolding in the context of an accelerating climate crisis that is having profound effects on local and regional agro-food systems around the world.

To be clear, unmasking the structures of the global economy and uncovering the legal techniques used to shape and succeed in distributional struggles over land and food does not provide any sort of recipe or roadmap for changing these outcomes. But it does allow us to begin to see that things could have been—and still could be—different.