The Texas blackouts have reminded us once again of the vital importance of electricity as part of the basic infrastructure of everyday life and the terrible consequences that ensue when the grid fails. Recent reports indicate that dozens of people died as a result of the extreme weather and blackouts and many Texas residents have continued to struggle with a lack of basic services. As has been widely reported in the media, the rush to blame wind energy and all things green for the blackouts has been thoroughly debunked. The plain truth of the matter is that all generation resources in Texas were affected by the extreme winter weather. And because Texas is especially dependent on tight coupling of the natural gas supply system and the electricity system, compounding failures in those systems meant that Texas lost substantial thermal generation capacity just when it needed it most.

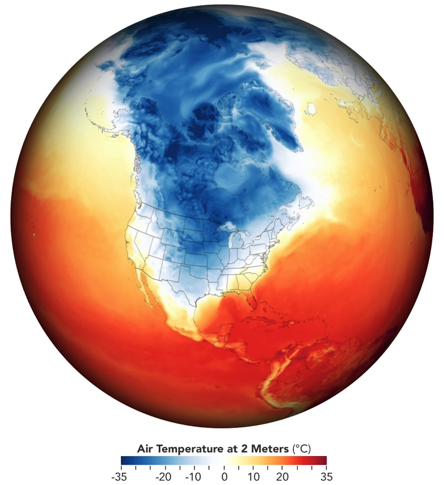

Like the heat wave in California this summer that led to rolling blackouts, the recent arctic freeze in Texas was, by historical norms, an extreme event outside the bounds of what the system was designed for and beyond what planners had anticipated. During the depths of the crisis, parts of southern Texas experienced colder temperatures than parts of Alaska . . . in February! But it is critical to recognize that what happened was not unprecedented. Similar events occurred in 1989 and again in 2011, leading state and federal regulators to ask why so many Texas generators failed to invest in weatherization, especially given specific recommendations to that effect after the 2011 event. Bottom line: what happened in Texas was not, as one key architect of the Texas market has argued, simply the result of a freak weather event.

While it will take months to sort out exactly what happened, it is clear that the blackouts in Texas resulted in large part from particular choices about market governance and the specific ways of price making at the center of the Texas electricity markets.

Electricity Restructuring and the Move to Markets

Up until the 1990s, electricity in the United States was provided almost entirely by large, vertically integrated Investor Owned Utilities (IOUs) regulated by Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) under a cost-of-service model. Starting in the 1960s and accelerating during the economic crisis of the 1970s, this basic model of rate regulation was subjected to a sustained critique by economists and lawyers, many of whom were associated with the University of Chicago. As deregulation gained momentum across the economy, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and a large number of states moved to restructure their wholesale and retail electricity markets in the hopes of tapping into the benefits of competition promised by the neoliberal vision. Along with California, Texas pioneered electricity “deregulation” (or, more appropriately, restructuring) in the 1990s and early 2000s. And although California pulled back partially after the western energy crisis of 2000-01, Texas has gone all in. Meanwhile, about a third of the states chose to stay with the basic model of cost-of-service rate regulation.

The Texas story is distinctive for at least two reasons. First, the Texas electricity grid is an island, unconnected from the large eastern and western grids. This means that Texas has full jurisdiction over both wholesale and retail electricity markets. Unlike the rest of the lower 48 states, FERC has no regulatory oversight over wholesale power transactions in Texas. Second, unlike the organized electricity markets in the eastern United States, Texas has adopted a market design for its wholesale electricity markets that relies almost entirely on the day-ahead and real-time electricity auctions to compensate merchant generators and encourage new investment (what is known as an energy-only market design). In simplest terms, this means that because of the uniform clearing price design that all wholesale electricity markets have adopted in the U.S. (a design that pays all generators the clearing price established by the last unit of generation needed to meet demand), the Texas markets rely on the prospect of massive inframarginal rents during peak periods (such as the recent crisis) when the maximum price cap is reached to encourage ramped up production and new investments in low-cost generation. Under this system of scarcity pricing, generators in Texas do not have an obligation to perform and there is no requirement that prices be “just and reasonable,” which has been a core commitment in public utility law since the early twentieth century. In effect, the rents available under scarcity pricing are intended to provide sufficient incentive for generators to participate in the market and to build new generation for the longer term.

Markets in Crisis

One key takeaway from the Texas blackouts is that an overreliance on the prospect of huge profits for a few days of the year as a way to stimulate investment in sufficient long-term generation capacity may be problematic in a climate-changed world where the grid will be subject to extreme weather events far outside historical norms. Another related takeaway is that generators have limited incentives in this system to invest in weatherization and redundant capacity, which is why the Texas Governor recently called for new legislation to mandate such investments. Finally, as we have seen in other crises, such as the 2000 blackouts in California, this particular market design can also create incentives for strategic withholding of certain generation units during periods of peak demand and other forms of gaming in order to drive clearing prices higher for a firm’s remaining generation units that continue to participate in the markets.

There are some important questions here that will have to wait for the forensic reconstruction of precisely what happened during the crisis: Where did all the money go? Was there manipulation? Did the sustained period of high prices actually encourage any additional generation to come on-line during the crisis? What we do know is that a substantial portion of generating capacity in Texas (close to 50% at one point), including natural gas, wind, solar, nuclear, and coal, was taken offline or unable to operate during the extreme weather event. With supply falling and demand increasing, the Texas grid manager, ERCOT, ordered deep cuts in electricity demand (or load) in the form of rotating outages to reduce the strain and avoid collapse. ERCOT estimated that Texas was 4 minutes and 37 seconds away from a total system failure of cascading blackouts that could have lasted for months.

In response to these events and consistent with its commitment to scarcity pricing, the Texas PUC ordered ERCOT to set prices at the System Wide Offer Cap of $9,000 per MWh for the duration of the time load was being shed—a price that is some nine times higher than price caps in other wholesale electricity markets and more than 400 times higher than the average wholesale power price in Texas of around $22 MWh. These extreme prices remained in effect for several days, leading to extraordinary profits for those generators that were able to continue producing power and to massive corresponding wealth transfers from those who had no choice but to continue purchasing power.

Not surprisingly, some are calling on the Texas PUC to intervene and order ERCOT to retroactively reprice real-time electricity prices during the critical period. Last Thursday, ERCOT’s independent market monitor sent a letter to the Texas PUC concluding that Texas kept wholesale prices “artificially high” for 33 hours longer than warranted during the crisis, resulting in $16 billion in excess charges to customers. The independent market monitor recommended that the Texas PUC retroactively revise the real-time energy prices for the 33 hour period in order to mitigate the “substantial and unjustified economic harm” that will result from leaving them in place. On Friday, however, the Texas PUC declined to follow the market monitor’s advice and reprice the power markets. The stated reason: too many hedging contracts and other private transactions tied to the market prices. As the new PUC Chairman Arthur C. D’Andrea put it: “It is impossible to unscramble this sort of egg.”

The Fallout

The political fallout from the crisis has been swift. The Chairman of the PUC resigned abruptly. Another commissioner stepped down earlier this week. Multiple ERCOT board members have resigned. The CEO of ERCOT was fired. And the Governor and other political leaders are racing to get on the right side of a public that is angry and demanding answers.

The financial fallout is just beginning but may prove to be more consequential. Some wind farm operators that were unable to produce but were obligated to purchase electricity on the open market during the period of extreme prices because of specific contractual provisions are now in financial distress and ripe for takeover by their Wall Street counterparties. The state’s largest and oldest electric cooperative, Brazos Electric Power Cooperative, which had an A+ credit rating before the crisis, has filed for bankruptcy protection. Multiple other cooperatives and retail electricity providers are likely to follow suit. And some retail customers are facing bills in the thousands of dollars.

The impacts on retail customers are important to emphasize. While all Texas retail customers will end up paying higher prices as a result of the crisis, a select few (around 45,000) who signed up for a specific rate plan that mirrored the wholesale market price are highly exposed. Many of these customers apparently used a company named Griddy (you can’t make this stuff up) to procure their power. As one of the purest forms of dynamic marginal cost pricing of electricity that one can find, Griddy offers customers an opportunity to adjust their demand in response to real-time price signals from the wholesale market.

According to the standard neoclassical economic view, these customers are model economic actors. Indeed, this form of marginal cost pricing of electricity for retail customers has long been the holy grail of economists and market designers seeking to develop competitive markets for electricity and other formerly regulated industries (promoted most famously by Alfred Kahn, the former Chair of the New York Public Service Commission and the father of airline deregulation who once referred to airplanes with his characteristic wit as “marginal costs with wings“). If customers can actually see and respond to the true marginal cost of electricity, the argument goes, the price system will work its magic and ensure that supply and demand are balanced and that the market is efficient.

But during the recent crisis, the Texas grid was pushed to the breaking point and Griddy’s retail prices jumped to $9/KWh for several days, a reflection of the $9,000/MWh price cap in the wholesale markets. Given the arctic conditions across the state, of course, most of these customers had little choice but to keep using their electricity. Now facing bills in the thousands of dollars (one Griddy customer reported a bill of $16,752!), some of these customers will end up in severe financial crisis if they do not get some relief.

The Texas Public Utility Commission has intervened, issuing two orders blocking retail providers from sending bills or disconnecting customers. And some Texas politicians have even called for federal relief for Texan’s utility bills. Central planning never looked so good.

Ways of Price Making and the Challenge of Market Governance

What to do? One big question looming behind the Texas meltdown is whether Texas customers, and other customers in deregulated markets across the country, have actually benefited from deregulation and retail choice. This has been a long-standing debate in the extensive literature on electricity restructuring for two decades. Competition, according to the proponents of deregulation, will do a better job of disciplining prices and delivering savings to customers because it will avoid all of the pathologies of rate regulation, and especially the tendency of regulated to utilities to over-invest in their physical assets and overcharge customers. But the record on deregulation so far has not exactly been a huge victory for consumers. Yesterday, the Wall Street Journal reported on its own investigation finding that “U.S. consumers who signed up with retail energy companies that emerged from deregulation paid $19.2 billion more than they would have if they’d stuck with incumbent utilities from 2010 through 2019.” And an earlier Texas-specific analysis, also in the Wall Street Journal, found that since 2004 Texas electricity bills have been $28 billion higher for those customers who have participated in the deregulated retail market than for those who have been able to stay with a traditional public utility.

Another big question raised by the Texas crisis is whether marginal cost pricing for a necessity such as electricity, for which demand is often highly inelastic (especially during extreme weather!) is all it’s cracked up to be. In fact, many customers may not view electricity as a commodity. Rather, they (we) often take it for granted as part of the basic infrastructure of everyday life and many of us prefer a stable and predictable monthly bill. This is especially true for older customers, low-income customers, and others who are confined to their homes because of illness or, say, a pandemic. But it is also appropriate for less vulnerable users who are not dedicated to comparing rates on a regular basis. To put it bluntly, few people are interested in being an energy day trader for a few dollars a month in savings.

Prices for electricity, like the prices for other essential services, are more than just signals. They are also relationships and those relationships can be coercive during times of great need. The ways in which we decide to make prices for these essential services (that is, the ways in which we design and use regulation, including market design, to generate prices) have serious implications for people and their ability to get on with their lives.

At the end of the day, the Texas blackouts remind us that an electricity grid operates as one big machine that must perfectly balance supply and demand in real time, all the time. The challenges of imposing market structures on this machine are immense, as we have learned repeatedly over the years, and will surely increase as climate disruption accelerates. And the stakes are only getting higher as the push to electrify everything accelerates. But whatever market design we choose, it is clear that the visible hand of government and the much maligned exercise of planning will need to be deployed with skill and care to manage these markets and to ensure that the ongoing effort to decarbonize the power sector proceeds in a manner that continues to provide affordable and reliable electricity to all customers.