This post argues that race and racism are segmenting the new “on demand” labor markets, in ways that facilitate the transition to this new sector of the economy. Scholars of racial capitalism have argued that modern capitalism could never have gotten off the ground without the violence of slave labor in the cotton economy. Violent racism operated to segment plantation workers into free and unfree labor, and unfree labor made cultivating cotton in bulk possible, facilitating the transition to industrialized cotton production and then to industrialization more generally.

Likewise, I argue here that race and racism are segmenting the new labor markets into more free and less free labor, and that this segmentation plays a central role in the transition to the new economy. Platform-based “on demand” service firms like Amazon and Instacart rely for their flexibility on a core of so-called “motivated” gig workers—workers whose economic survival depend on gig work. As it turns out, these workers are “motivated” because they are workers of color who are less free to turn down unstable work, or to bargain for a wage premium for doing risky, back-breaking or otherwise odious work. As we’ll see, race does very important work in constituting this segment of the workforce, and in keeping this core of workers “motivated.”

Jack Be Nimble, Jack Be Quick

The new economy differs from the old in many ways, but chief among them is the need for firms to be able to adapt quickly, to be nimble, to be able to turn on a dime. The business model behind the on-demand economy is a just-in-time workforce, which adapts constantly to meet changing consumer demand, requiring far more labor-market flexibility than before. In a world where demand changes quickly, firms that are more flexible or nimble will out-compete firms that are slower to change.

In such an environment, firms compete by becoming “assetless,” relying on resources outside the walls of the firm—partners, allies, contractors, subcontractors and temporary workers—to ramp up or restructure quickly with minimal cost. Severing long-term responsibility for the workers who create value saves firms the costs of health care, overtime, retirement planning, and more. Beyond these cost savings, being assetless, and in particular, workerless, allows firms to scale their workforce up or down dramatically in a short period of time, responding to sudden changes in demand or the accelerated timeline of a technology launch.

Instacart, the platform-based online shopping and delivery service, is a great example of this shift to flexibility as a source of comparative advantage in the “on demand” economy. Instacart’s online platform connects customers to over 6,000 shoppers in 15 major cities at a range of partner stores. Workers who shop for groceries receive a digital shopping list from customers and then pick out items (or substitutes) using the customer’s credit card to pay. Delivery drivers then bring the groceries to the customer’s door. Workers are compensated based on a formula that factors in the number of items per order and the number of orders per shift, and some shoppers are timed. In comparison to other grocery delivery services like Kroger or Whole Foods, Instacart’s competitive advantage comes from the fact that it has no permanent work force, no infrastructure, no real property or other assets to constrain its strategic choices.

Amazon uses the same workerless approach to manage flexibility with regard to one of Amazon’s major challenges, which is the so-called “last-mile logistics” of delivery. Instead of hiring part-time employees or using FedEx or UPS, Amazon has created Amazon Flex, an army of independent contractor drivers. In an effort to ensure stability of their workforce during periods of high demand while reducing labor costs in periods of low demand, companies like Instacart and Amazon recruit a very large contingent of workers to scale up as the environment dictates.

Partly in response to the glut of new workers, the company then drastically cuts hours and pay for their workers in the period after ramping up, which then operates to scale back the workforce to lower levels. Instacart shoppers and delivery personnel alike report that after initial success with the company, typically during a high demand period, both hours and pay go down, for shoppers by as much as 19%, and for delivery-only workers from between 6 and 21%.

To maintain both flexibility and a reliable workforce, companies depend quite heavily on a central core of gig workers who will not desert the firm despite the precarity of their work. Indeed, Instacart’s CEO, Apoorva Mehta, reports that the company’s primary challenge is attracting and retaining this core of workers who will remain available despite crappy jobs–dramatic variation in both hours and wage, none of the traditional incentives of benefits like health care, overtime or retirement to keep them available, and back-breaking, often dangerous or risky work without adequate training.

Unfree Labor and the New On-Demand Labor Markets

Recent research shows that race is doing the work of creating this all-important central core of reliable gig workers who can’t refuse crappy jobs. Workers in the on-demand economy can be divided into two general categories. The first category is motivated gig workers, defined as workers who make more than 40% of their income through gig work or describe the work as their primary source of income. The second category includes casual gig workers, who don’t fit into the motivated category.

A recent survey of 3000 workers by the Aspen Institute and TIME Magazine sheds light on the work that race does to segment these groups, and to constitute the all-important motivated workers group. Approximately 14.5 million workers (about a third of the workers in this economy) are motivated workers, meaning that they make more than 40% of their income through their gig work, describe their work as their primary source of income, or say they can’t find traditional employment. A whopping 68% of these workers are people of color. 74% are male and 57% are between the ages of 18 and 34. These workers tend to live in metro-heavy states, like New York and California. Relative to motivated workers, casual workers are more racially diverse. Still, 49% of this group is made up of people of color. Fewer of this group are men (54%) and fewer are millennials (between the ages of 18 and 34).

Race makes these motivated workers less free to refuse precarious work with little or no benefits. Workers of color are less likely to find work in stable employment, for several reasons. Workers of color have fewer of the required educational credentials to qualify for more stable work, in large part owing to racially and economically segregated neighborhoods, particularly for Latinx and some Asian workers, but also for black workers. These credential differences affect the likelihood that tech-heavy platform firms will hire workers of color for more stable employment.

Research confirms that workers of color are more also likely to suffer from racial discrimination in hiring and retention, for reasons having to do with both intentional discrimination and implicit bias. Because workers of color have fewer options than their white counterparts, they are less free to refuse precarious work, and are more likely to form the core component of motivated workers on which the on-demand economy relies.

Racial segmentation of the new labor markets may be worsening particular kinds of racial segregation in labor more generally, even as other types of segregation improve. Scholars have begun to evaluate the kind of segregation that results from the racial dynamics of population turnover, as new firms enter and old firms die out over time. If firms entering the market are on average more racially homogenous than firms exiting the market, then what I will call “turnover” racial segregation will increase over time.

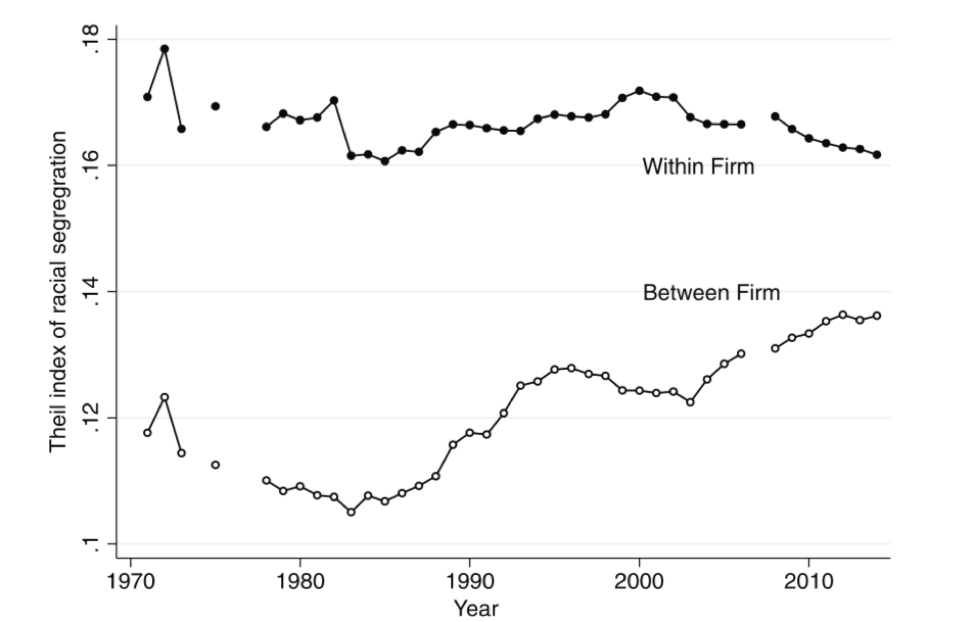

As the graph below shows, turnover racial segregation has significantly worsened in the last ten years owing to racial differences between entering and exiting firms, designated in the graph as “between firms.” This turnover segregation begins to increase significantly beginning around 1990 and then spikes even more dramatically around 2005 or so. This is true even as the general level of integration within the average firm (“within firms”) has remained flat over time, or even begun to decrease over the last few years.

Turnover Segregation (Between Firm) vs. Within Existing Firm Segregation: 1970-2014

Scholars suggest that this increase in segregation from firm turnover, particularly the dramatic spike in the mid 2000s, might well be attributable in part to the way in which racially homogenous platform players are replacing more integrated firms who are on their way out. As suggested above, platform players might well be more racially homogenous because they enter the workplace having already hived off functions once filled by people of color in-house. So we might expect to find that Instacart is more racially homogenous in terms of workers who design and maintain their platform, especially compared to older, soon-to-exit firms who might have employed delivery people in house.

One last thing to note. As mentioned above, I find it both illuminating and ironic that the core group of reliable workers who are less free to refuse precarious work is called “motivated” by the experts who study them. In fact, motivated workers are “motivated” because they are less free to refuse really bad jobs. It is this precisely this lack of freedom that firms in the on-demand economy exploit to jump-start their new ventures, much as plantations exploited unfree labor to extract the profits that gave rise to modern capitalism. Even as we shift to new ways of using technology and new modes of economic activity, it would appear that we still depend on race and racism to get those new modes of capitalism off the ground.