This post is part of a symposium on root and branch reconstruction in antitrust. Read the rest of the symposium here.

***

For years now, labor unions and their allies have accurately identified the so-called gig economy as an existential threat to whatever shred of worker power and labor standards remains in the US economy. Where gig workers lack the legal status of employees, they exist beyond the reach of labor and employment protections. The unprotected status of this segment of the workforce can then be used to threaten, intimidate, and ultimately replace workers who enjoy legal protections. The underlying principle isn’t new, nor are the contours of the legal and political battle around it: who counts as a worker is in part determined by who counts as an employer, and many, many employers have realized they can escape an employer’s responsibilities under the law by controlling and directing their workforce at an apparent distance, hiding behind franchisees, contractors, and staffing agencies as employers of record, or, as in the case of the gig economy, claiming there simply is no legal employer.

While the stakes in the fight over regulating the gig economy are fairly obvious, unions, workers, and their allies have, to date, only fought half the battle: they have tried to defend the definition of employment against technology-enabled erosion so as to encompass more workers within the bounds of labor regulation and federal protections for collective action and union representation. For the most part, they’ve lost. Prop 22 and similar gig company-sponsored initiatives have gutted (or are in the process of gutting) more inclusive tests for employment status. Meanwhile, the gig business model is being extended into other industries, like healthcare. And the primary messaging from the platform companies continues to resonate with both policymakers and workers: gig work represents an improvement in labor standards above what would be available were they classified as employees, because it means work hours are flexible.

The dire state of labor standards for workers who are classified as employees doesn’t help matters. What many gig workers want is what platforms promise, but don’t deliver: genuine independence and control over their own work. It’s hard to convince them that they should seek those things through the protection of employment and labor law when those protections do not, in fact, reverse the dehumanization and exploitation that is still the reality of market labor. Forming a stable union in a nonunionized workplace remains near-impossible, especially where turnover is high, and very few existing union contracts meaningfully grant employees anything like the control and genuine independence workers seek. Indeed, four decades of neoliberal policies have so undermined regulatory protections that the benefits of government protection are difficult to identify for many workers.

That’s where antitrust comes in. Antitrust has a long tradition of securing the independence of the self-employed, by means of enforcement against what are known as ‘vertical restraints’ binding subordinate entities to dominant ones. Prohibitions on vertical restraints—such as dictating the prices that subordinates charge to customers and requiring that subordinates be exclusive to a single dominant firm—are what once made the gig economy illegal, since they prevent the exercise of control by a non-employer. They thus act as a necessary complement to labor standards: if a dominant firm wants to exercise control, then the robust antitrust regulation of vertical restraints and labor regulation together entail that the firm must thereby assume certain responsibilities (to pay at least minimum wage and overtime, to include employees in company benefits, to abide by civil rights and workplace safety laws, and so on). They must also not infringe on their workers’ right to bargain collectively and to undertake collective action. If employers do not want to assume these responsibilities, then they are obliged not to exercise control. Without this latter prohibition, enforced by antitrust law, employers will always seek to escape the legal construct of the employment relationship. The purpose of bringing antitrust liability to bear on gig economy firms is to force them back into it: taking away their ability to exercise control in the absence of an employment relationship is a necessary condition for the success of any effort to curtail the gig economy and the threat it poses to worker power and to workers’ welfare.

The remainder of this piece elaborates on the legal strategy that could, in fact, accomplish that end: reconceiving the gig economy business model as reliant on vertical restraints to inhibit competition between platforms in service of higher profits for platform businesses. It thus outlines an antitrust theory of harm that should be put to use by workers and their advocates as one crucial prong in the effort to address the threat posed by gig work to employees, to unions, and to workers who desire genuine independence and autonomy.

Vertical Price Restraints in the Gig Economy

The tech platform business model rests on acting as a dominant intermediary between a suite of upstream goods- or service-providers and downstream customers. Earning a profit in that role means charging a high ‘take rate’ on transactions that occur on the platform. In the case of app stores, typical platform shares of gross revenue from customers are around 30% for installment fees and in-app purchases, while journalistic sources suggest that number is in the range of 35-38% for gig platforms, where there’s no published standard rate. Earning that cut depends on both sets of counterparties (upstream suppliers and downstream consumers) having nowhere else to go; otherwise, the parties would be able to circumvent the middleman and do business in a mutually-beneficial way, by escaping the platform’s cut and sharing it out in the form of lower prices and higher pay. The vertical restraints that are typical of the gig economy are aimed at preventing such multi-homing; platform competition, by contrast, requires the existence of true multi-homing, whereby the take rates that platforms charge are subject to competition from other platforms, or new entrants.

Many such vertical restraints operate in the gig economy. First and foremost, the platform sets the prices for these putatively independent transactions (between, say, a rideshare driver and his or her customer), to which the platform is not legally a party, according to its own pleading. That is what’s known as resale price maintenance (or “RPM”) in the antitrust parlance of vertical restraints. If the driver can’t set the fares that customers pay, there’s no means by which customers could be steered to lower-take-rate, higher-paying platforms by charging lower fares on that platform. That, in turn, means there’s unlikely to be price or wage competition between platforms in the first place. The incentive on the part of platforms to cut prices and/or increase wages is blunted if neither set of counterparties can steer the other, so the result is walled gardens with high prices, low pay, and little multi-homing or competition. It is, in effect, a tacitly collusive equilibrium sustained by vertical restraints preventing drivers from setting prices (as well as an overall oligopolistic market structure), instead of the more straightforward (and legally risky) horizontal agreement between the platforms not to reduce prices or increase pay. Still, the economic effect is the same.

Antitrust scholars have pointed out that so-called “Most-Favored Nation” clauses (“MFNs”)—requiring vendors on a given platform not to offer their services at a lower price on other platforms—impair platform competition by inhibiting steering, which serves to increase prices across the board. If vendors offer a lower price on one platform, the MFN means they would have to match that price elsewhere, substantially preventing any steering through price competition that might reduce platform take rates. The resale price maintenance that gig economy platforms practice is a super-charged version of an MFN, since the platforms are directly setting the prices instead of restricting the autonomy with which vendors do so. In combination with an oligopolistic market structure in which all platforms use RPM, the result is, if anything, more anti-competitive than the typical platform MFN.

Rideshare platforms would be particularly vulnerable were price competition to break out, because they practice price discrimination among their customers, which relies on customers who are charged a high price having nowhere else to go. (A particularly egregious example of this is highlighted in the recent DOJ case against Uber for violating the Americans with Disabilities Act by charging customers higher fees if it takes them longer to get in the car.) Rideshare customers charged a high price would be sensitive to lower-priced offers on an alternative, higher-paying platform favored by drivers, but they don’t have that option because drivers are restrained from setting prices at all.

Vertical Non-price Restraints in the Gig Economy

Beyond the inability to set prices so as to steer customers to lower-cost platforms, incumbent gig platforms use a variety of tools to enforce the loyalty of their drivers in ways that impair platform competition. Before going further, it’s worth briefly describing how gig work functions in practice: ‘activated’ workers receive gigs offered by the platform, which they notionally have the discretion to accept or reject. They do not get paid for the time they are activated-but-undispatched. Nor do they get paid for the time between accepting an offered gig and beginning the task itself. Thus, the compensated time, when they are actually performing the service, has to offset the uncompensated time during which the workers await fares, or else gig workers operate at a loss. The purpose of taxi price and entry regulation is to ensure this is the case, but of course there’s no external authority regulating fares or entry in the gig economy in most jurisdictions.

The absence of such an assurance means that workers have to be very discerning about which customers they accept or reject. If they reject too many, they don’t accrue enough compensated time to offset their operating costs. But if they accept the wrong customers, then they operate at a loss in any case. Who are the wrong customers? The ones whose destination, current location, or willingness and ability to pay means that there will be a large block of uncompensated ‘deadhead’ time and/or distance at the other end of the trip, or who will be charged too low a price (at the platform’s discretion) to make the trip worthwhile for the driver.

This is where platform deception comes into play. Workers are typically told neither the fare nor the destination of an offered gig in advance. They are only told vague information about the location of the start of the trip (such as the distance from the driver’s current location), which they must accept or reject on that basis alone, with only a few seconds to decide. If they cancel an accepted gig after learning information that indicates it will be unprofitable to undertake, they risk de-activation from the platform entirely. Meanwhile, the platform knows both the origin and the destination of each trip, and of course the platform itself sets the fare based on what it already knows the customer is willing and able to pay. The platform knows that some gigs are less profitable than others, but it promises to serve all its customers and to do so with a minimal wait time. Thus, the platform seeks to induce workers to accept unprofitable gigs, through a variety of means as described below, all of which cross the bounds of illegality.

Non-linear Pay

Gig platforms typically reward workers for accepting a high percentage or a large number of offered gigs. Both of the dominant rideshare platforms, Uber and Lyft, use versions of the following system: they divide the week into two segments, Monday-Thursday and Friday-Sunday. Before the start of a given segment, they offer several lump sum payment options to drivers in exchange for accepting a given number of offered gigs. Accepting an offered lump-sum payment for one or the other platform for a given week segment amounts to a reward for single-homing on that platform for the duration of the segment, since it’s not possible to achieve bonuses for both platforms at the same time.

In theory, drivers still have the ability to reject some offered gigs from the platform whose bonus they’ve agreed to without foregoing the bonus, but in practice, doing so means that the platform has all the power to prevent drivers from hitting the bonus thereafter, since it has the discretion to offer or not offer further gigs before the end of the segment. The platforms use these bonuses to line up their workforce in advance, based on their forecasts of demand, without bidding against one another in the moment for drivers’ time, which would have the effect of reducing take rates, to the benefit of drivers. Finally, the terms of these lump-sum payments worsen as drivers gain experience on the platform. Apparently, the companies believe that the payments are needed only to ‘hook’ the drivers and induce them to make costly investments in the work, leading to lock-in and reduced labor supply elasticity over time.

These lump-sum payments are not the only forms of so-called “non-linear pay” that gig platforms employ. They also offer rewards for accepting a given number of gigs in close succession, in effect a short-term noncompete agreement. They also designate bonus areas where drivers can earn a premium on the base fare. According to “Rideshare Guy,” a blog run for the benefit of drivers and at least partly funded by Uber, without achieving such bonuses, “being a profitable driver is almost impossible.” For that reason, the overall system operates as a non-linear pay structure designed to create dependence on the part of workers (in economic terms, to reduce their residual labor supply elasticity vis-a-vis any one platform), which in turn enables the platform to worsen labor standards and destroy any notion of ‘flexible work,’ since the worker has no real ability to leave. It’s worth pointing out that these non-linear pay schemes are crucially different from canonical piecework, in that the latter is linear pay on the basis of output rather than time. Piecework is (correctly) thought to be anti-worker because it shifts the risk of output fluctuations or market conditions like price fluctuations from employers to workers. Non-linear pay is anti-worker because, in addition to doing those things, it operates to tie workers to a single employer.

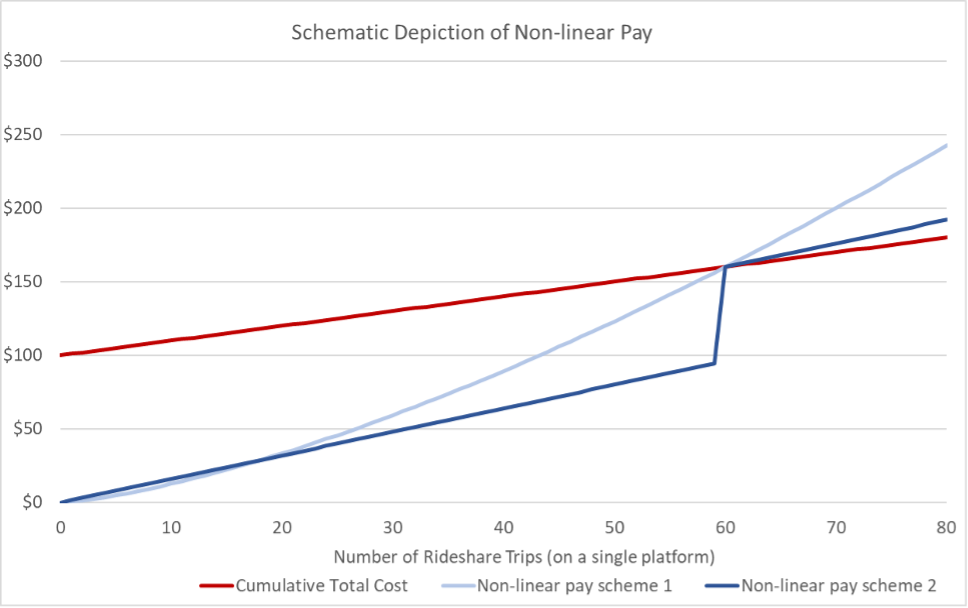

This figure visualizes non-linear pay in the rideshare industry. The horizontal axis plots the number of trips a driver undertakes (in a week or week segment, for example). The red series shows the total cumulative cost of undertaking that many trips. In this case, the cost consists of a fixed cost of $100 (an auto loan payment + insurance, for example), plus a variable cost of $1 per trip (gasoline and depreciation). The two blue lines plot two different schemes for non-linear pay, both of which are such that the driver would just break even if he or she drove 60 rides for that platform. Scheme 1 has increasing per-trip pay as the driver undertakes more trips, and scheme 2 has a lump-sum bonus for driving 60 trips. Scheme 2 is more similar to what rideshare platforms actually do, but regardless of which scheme the platform uses, such a pay structure means that drivers are impelled to single-home on one platform, rather than entertain bids for their labor in real time, in which case their per-trip pay would be higher. The non-linear pay scheme operates as a de facto non-compete clause.

If we take the platforms’ claim that gig workers are independent contractors at face value, these reward structures amount to the exercise of control across the legal boundary of the firm. The platforms’ ability to perform their basic function, connecting customers to workers and serving their customers promptly, depends on being able to exercise this control. Their profitability depends on doing so without assuming the responsibilities guaranteed under labor law. But there have been several antitrust cases targeting such loyalty rebates where they have the effect of impeding competition, which has arguably been the case among gig platforms as well: entrants that have tried to offer more worker-friendly terms in the hope of attracting workers to their platform and thus being able to offer customers faster wait times have failed for a variety of reasons, among them that workers can’t afford to risk abandoning the incumbent platform entirely, and doing business at all means doing business on their terms, i.e. with single-homing restraints in place. (Uber, it should be noted, engaged in both predatory pricing and tortious interference directly against its would-be rival Sidecar exactly to cut the threat of multi-homing off at the source, for which it recently paid out a settlement after losing a motion to dismiss Sidecar’s monopolization case.)

Minimum Acceptance Rates in Exchange for Data

Another so-called “non-price” vertical restraint is minimum acceptance rates in exchange for data-sharing. In some jurisdictions, drivers who want to see data about fare and destination in advance of deciding which trips to accept or reject are required to maintain a minimum acceptance rate—which, of course, defeats the entire purpose of seeing it in the first place. The reason the data is valuable to workers is to enable them to make informed decisions about which gigs will be profitable, so that they can accept those and reject the others, which is supposedly at the core of the concept of independent work. But the minimum acceptance rate means drivers must nonetheless accept offered gigs even when they’re unprofitable. In the parlance of economics, the data increases drivers’ labor supply elasticity; the minimum acceptance rate reduces it.

This gets to the heart of the lie that independent work is “flexible.” Workers may be able to decide for which hours they activate, but once they do so, virtually every economically-significant aspect of the job is controlled and decided for them, and frequently against their interest. Moreover, platform control functions to prevent platform competition from arising, and along with it, the possibility that competing platforms might increase consumer surplus by charging lower fares and attracting drivers with higher pay to serve their customers promptly. By means of vertical restraints on drivers and the tight duopoly in rideshare and tightening oligopoly in food delivery, all three sets of counterparties—workers, customers, and restaurants—lose out.

Antitrust as Remedy

The practices discussed in the preceding sections—resale price maintenance, non-linear pay, and minimum acceptance rates—would be legal if the workers in question were employees, because employees can be obligated to undertake certain work by their employer and not to work for anyone else during the duration of their employment. But in that case, gig employers would be obligated to maintain labor standards.

Which brings me to remedies. Antitrust remedies typically take the form of damages and/or injunctions. Workers have been damaged by all of the conduct described above, resulting in much lower pay and higher take rates for the platforms than would have prevailed in their absence. An antitrust case could also enjoin the restraints at issue. A world where gig workers enjoy full data-sharing, linear (and transparent) pay, and discretion to set their own prices for consumers is a world where the returns to gig work are much higher. It’s possible—likely, in fact, given what gig platforms have said in response to more aggressive labor regulation in other jurisdictions—that in the event of such an injunction, platforms would instead opt to reclassify their workers as employees. And even if they did not, gig workers should still have the right to undertake collective action outside the remit of the National Labor Relations Act, as Sanjukta Paul, Sandeep Vaheesan, Shae McCrystal, and others have written.

In 2014, three senior officials of the Federal Trade Commission sent a letter to a Chicago city alderman opposing any effort on the part of municipal governments to regulate the rideshare industry, on the grounds that the industry was injecting competition into local taxi markets, to the benefit of customers. The authors of that letter particularly praised the use of surge pricing to equate supply and demand in real time, lowering wait times. The rideshare and food delivery platforms got what they wanted, including from those three officials: very little local regulation, and so far, no antitrust scrutiny from state or federal enforcers. Meanwhile, in 2017, both sitting commissioners of the FTC as well as Trump’s Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust filed a brief in an antitrust case on behalf of Uber claiming that collective bargaining by rideshare drivers violates the Sherman Act. The platforms’ public relations campaign worked as intended.

The primary problem with the officials’ argument is that the platforms abandoned the surge pricing those officials claimed made rideshare an improvement on traditional taxis when it turned out to be unprofitable. Customers might still see surges, but drivers don’t get the money, which means the surges can’t stimulate supply. The platforms set those prices to maximize the difference between what their customers pay and what drivers need to be paid to get them to work for the platform. The latter is a low number due to the use of anti-competitive price and non-price restraints that reduce workers’ residual labor supply elasticity and impair platform competition. The supposed experts who opined that the rideshare business model is pro-competitive apparently didn’t think very deeply about that business model before they decided to lobby on the rideshare platforms’ behalf.

Discussion about the relationship between antitrust and labor law, as well as between workers and entrepreneurs, that is confined to a counter-productive either/or serves no one’s interests except large, dominant employers, who have profited from the inability of any area of law or policy to meaningfully constrain their power. It’s time to put that zero-sum false tradeoff behind us, in favor of a larger vision that recognizes the unity of interest among the disempowered in every corner of the economy and seeks to forge a coalition that might actually have a hope of winning power in this country by securing for its people what they want: a decent standard of living without demeaning service to a brutal plutocracy.