In 2024, student-driven protests erupted globally. But perhaps the most significant occurred in Bangladesh, where mass protests ultimately led to the ousting of then-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. To help understand what transpired this summer and what the future might hold, the LPE Blog’s Chloe Miller spoke with Chaumtoli Huq about the history of political and economic discontent that fueled the protests, the challenges facing Bangladesh’s interim government, and the lessons that other social movements might draw from the uprising.

** ** **

This past summer, a student-led protest movement ousted Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina. What sparked this movement, and what were its main goals?

The student-led protest movement that culminated in the ousting of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in 2024 has its roots in deep structural issues within Bangladesh’s political and economic systems. While the initial catalyst was the reinstatement of a civil service job quota for descendants of the 1971 Liberation War veterans, the protests were underpinned by broader dissatisfaction with a regime seen as increasingly authoritarian, corrupt, and economically exclusionary.

The protest movement began in June 2024, after the Supreme Court of Bangladesh reinstated a quota that reserved 30% of civil services jobs for descendants of those who fought in the Liberation War. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government previously annulled the quota through a 2018 executive order, which was issued in response to a then-ongoing quota reform movement that mobilized youth nationwide. The Supreme Court’s reversal and reinstatement of the order seemed to deal the final blow to the long-standing demands students had mobilized around for years.

The central critique of the quota was that it functioned as a form of political patronage and was increasingly used to consolidate the power of Sheikh Hasina’s regime, which had grown more autocratic over the past fifteen years. Underpinning the movement was also an overall frustration with the lack of economic opportunity in Bangladesh. University students, often from working-class backgrounds, could not find stable post-graduate employment. While Bangladesh has experienced economic growth since its independence, opportunities remained limited for the middle- and working-class populations.

After the court struck down the executive order, students quickly took to the streets, with peaceful protests breaking out across university campuses. Shortly after the mobilizations began, Sheikh Hasina made controversial comments about the students, calling them razakars, or traitors. Sheikh Hasina’s reaction is emblematic of her reign – over the past fifteen years, there has been horrific state backlash to nearly any dissent expressed against the government. This includes the imprisonment of Mir Ahmad bin Quasem Arman, who was detained in a secret prison in Aynaghor, as well as human rights lawyer Adilur Rahman, journalist Rozina Islam, and photographer Shahidul Alam, among many others.

Once the Prime Minister made her controversial remarks, there was an immediate escalation from the protestors and a rapid deterioration of the government’s tolerance for the mobilizations. Students’ frustration with the economy, coupled with the government’s long-standing suppression of civil society, ignited the students to step up their movement. They began to shift the conversation beyond just quota reform and mobilized a broader coalition united around a struggle for democracy and against fascism. Soon, we saw government-imposed curfews and internet bans. And, most horrifically, we saw the Bangladeshi army being empowered by Sheikh Hasina to shoot on site for violations as small as breaking curfew. As the violence continued to escalate, the organizers narrowed their initial nine demands down to just one: that Sheikh Hasina resign.

When looking at the movement holistically, a few things become clear. First, there was pre-existing economic frustration. This was then combined with longstanding political repression. Finally, there was the seemingly choreographed legal push-pull between the Supreme Court and the government around the issue of if the quota could be modified through legislative response, which reaffirmed the long-held view that the judiciary was beholden to Sheikh Hasina and not independent. The quota reform being struck down was the match that lit all of these pre-existing conditions up.

How can we reconcile the economic discontent driving this movement with Bangladesh’s widely lauded status as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies? Is this a case of economic development being pursued at the expense of social assistance, of economic gains being unequally distributed, or something else?

We have to understand Bangladesh as a formally colonized country that went through its own recent independence movement in 1971. The British divided South Asia into India and Pakistan, with Bangladesh formerly being East Pakistan. The reasons underlying the 1971 independence movement were not just political – the population of East Pakistan wanted political representation and better access to the government it lacked at the time – but also economic. Bangladesh’s resources were being extracted by West Pakistan, and there was a struggle for autonomy and control over these resources.

When it gained independence in 1971, Bangladesh inherited an economic system reliant on the export of raw materials and labor-intensive industries. Bangladesh entered into the global economy at a time of peak neoliberalism, when most post-colonial countries were required to deal with the Bretton Woods institutions, including the IMF and the World Bank, to increase foreign investment. Investment was often contingent on developing countries agreeing to adjust their own governance structures, which has been referred to as neocolonial. This was presented as the only real path to further economic development under the global capitalist system.

However, following the Bretton Woods development model presented a tension: many of the leaders of the independence movement wanted to see Bangladesh as a socialist country, largely as a result of the hardship faced due to the extraction of British colonialism and Pakistan. The 1972 Bangladesh Constitution reflects this sentiment, with economic rights relating to equitable rural development and work as a fundamental right enshrined within it. But, to survive in the global economy, there was pressure to seek aid and not pursue uncharted paths that went against the dominant global capitalist world order, especially when powerful global actors like the United States were allied with Pakistan and unsupportive Bangladesh’s independence movement.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Bangladesh prioritized export-led growth and foreign investment at the expense of domestic economic sovereignty and social welfare programs. As a result, while sectors like garments grew, little attention was given to diversifying the economy or addressing the needs of the rural and urban poor. Bangladesh opened itself up to foreign investment by using cheap labor to attract companies. The two main ways the Bangladeshi economy has thrived are through the extraction of cheap labor for the export-oriented global garment industry and through migrant labor remittances. Certainly, Bangladesh’s economy has grown, which has benefitted the wealthy, but it has been at the expense of the most vulnerable populations in the country.

And this is really what the student movement was responding to – it wasn’t just about civil service jobs, but about a broader challenge to the impact of global capitalism and how it limits opportunities in Bangladesh, with the government maneuvering within this capitalist system to maintain its power. It is a larger critique of neoliberal globalization, which often leads to “jobless growth,” where economies grow but do not create enough quality jobs, especially for educated youth. Sheikh Hasina’s government long courted international investment while suppressing internal dissent and the voice of civil society, aiming to position Bangladesh as a middle-income country while leaving poor and working-class communities behind.

One distinctive feature of the uprisings, as I understand it, is that they melded a working-class labor movement focused on the allocation of civil service positions with a broader fight against fascism and an authoritarian regime. Can you speak to how these two interrelated struggles fed into each other to lead to the movement we saw?

One thing about the movement that was very unique was that the movement did not start and end with the capital city of Dhaka. Students from outside the capital mobilized and helped organize the entire country, creating a mass-supported movement. On August 4th, the students called for a march to Dhaka and invited everyone to join them. They specifically called for workers to unite with them – which was a crucial transformation in the movement. The movement’s intersectional approach, addressing issues of gender and indigenous rights alongside economic and political grievances, demonstrates its broad appeal and potential for systemic change. By uniting different social classes—students, workers, and eventually rank-and-file soldiers—the movement built a broad-based coalition against the Hasina regime.

While the quota reform movement was very much initially student-driven, by August, and for some of the factors discussed above, there was much wider support. People were united by economic discontent and a larger fight against a fascist government, especially after seeing the escalating egregious and violent state repression against the protestors. The August 4th march galvanized people who were otherwise not political, like housewives and parents, who took to the streets to ask, “Why are you shooting at our children?”

I think that moment is similar to the marches we saw in the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1960s. At the point of the march to Dhaka, you also began to see rank-and-file members of the army, many of whom are also children of poor families, begin to object to the orders to shoot on site. Pictures came out of this moment where the army is standing, not doing anything, alongside the protestors – no longer willing to follow Sheikh Hasina’s orders.

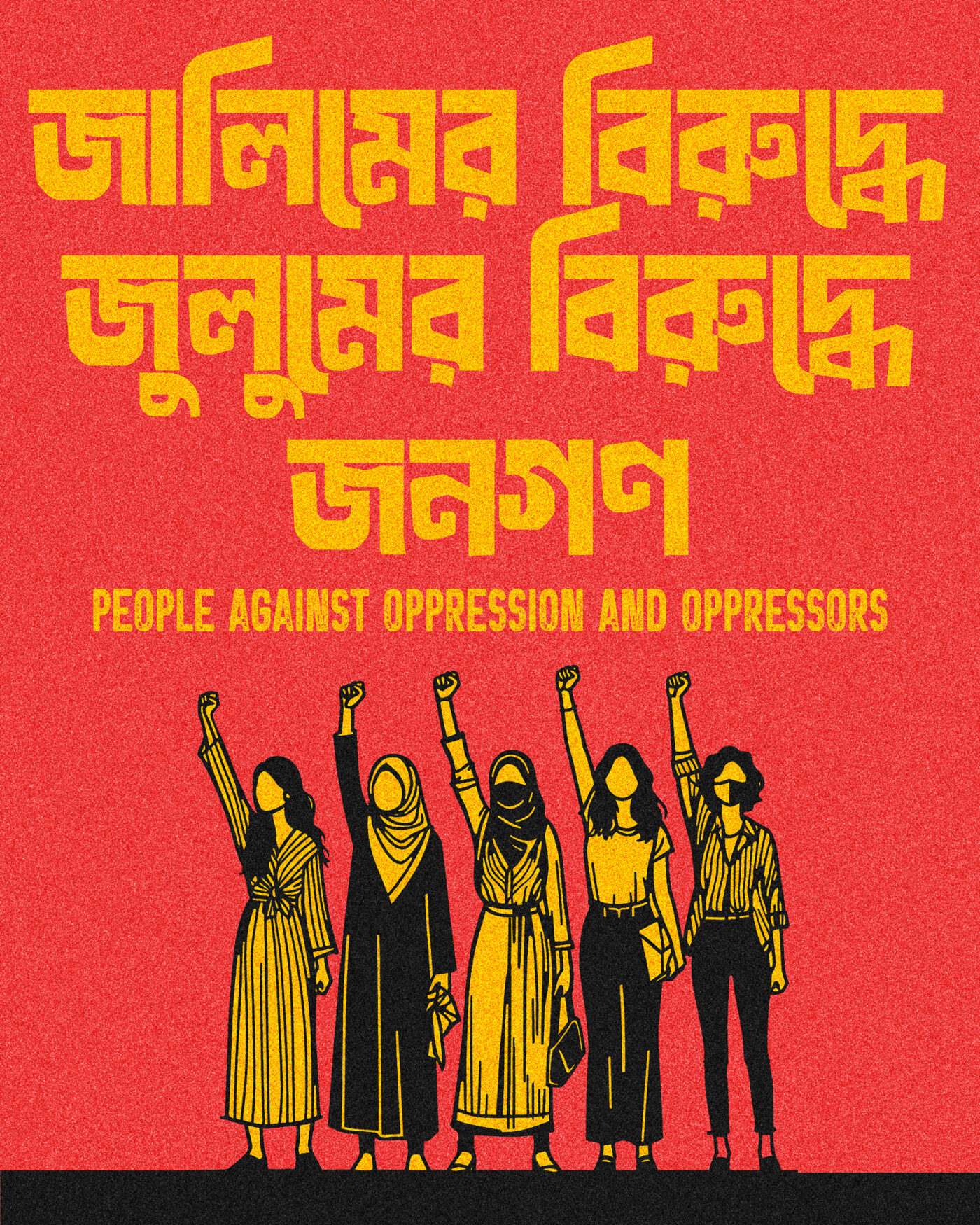

Image by Debashish Chakrabarty.

Reproduced with permission of the artist.

What role did misinformation play during the uprisings?

In the weeks after the uprising, there was a lot of misinformation spreading around news outlets that Hindus were being mass-killed in Bangladesh. Other outlets acknowledged that there had been instances of violence against Hindu individuals, but not based on religion – many of the individuals caught up in the violence were aligned with Hasina’s administration. In contrast, we saw orthodox Muslims visibly guarding temples, promoting the idea that we are all Bangladeshis, regardless of religion. The interim government has been quick to denounce communal violence, and many Hindu students in the movement have become vocal against misinformation campaigns targeted at sowing religious divides.

We also saw a calculated effort by Indian intelligence, along with national security pundits, to destabilize Bangladesh. For the last fifteen years, India has propped up Sheikh Hasina, and as a result, she entered into numerous trade agreements that were favorable to India. There has already been massive discontent in Bangladesh against India’s influence in Bangladesh. Moreover, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently had an election and faced a loss of parliamentary power. In part, I think some of the misinformation and destabilization of Bangladesh is aimed at better consolidating BJP power. As such, Bangladesh is placed in the center of regional politics – with countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, and others already attempting to move away from the influence of the Modi government and India’s hegemony in the region.

Misinformation is also rampant in Western characterizations of the student movement. For instance, Jeffrey Sachs, an American economist and the former director of the Earth Institute at Columbia, wrote a horrendous op-ed saying that the regime change could not have happened without United States involvement. Such a characterization is deeply insulting and reflective of neo-colonial attitudes, as it suggests that people in the Global South can’t really do anything on their own – govern themselves or be the architects of their own uprising.

What is the state of the government in Bangladesh today?

We’re more than a month post the establishment of the interim government, and there have been efforts to rebuild – it has been described as Bangladesh 2.0 and our second independence. After Sheikh Hasina fled, an interim government was formed nearly immediately. Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel Laureate and the founder of Grameen Bank, was appointed as the interim Chief Adviser. Notably, he formed an advisory group to help govern the transitional government, and two student movement leaders are included in the advisory group. This is virtually unprecedented.

When the government fell, the police abdicated their role. There was a worry that there would be lawlessness, violence, and complete disarray. Of course, there was some violence – you cannot have that level of power transition without some degree of chaos. But, thousands across the country also came together at this moment. Students started running traffic control. Others spearheaded beautification projects across the country.

And now, much is up in the air. We’ve forced the current government to resign through mass-based mobilization—now what? What does the economy look like? What does the law look like? Even Bangladeshi universities have to appoint new chancellors because the previous ones colluded with the government. The interim government is also gradually appointing new executives to government agencies because every institution has been tainted by political loyalists from the previous regime. The task before the transition government is enormous.

But I am hopeful. If you think about the youth that led the movement, they are in their early to mid-twenties. They have only experienced the regime of Sheikh Hasina, much of which had been autocratic and opportunity-limiting. Yet, they still feel such a responsibility to build the country that they want. In all my years of studying and organizing in transnational movement spaces, I’ve never seen such a massive scale of civic engagement. There is such a sense of optimism that we can finally build the country we want.

What major challenges do you think Bangladesh will face in rebuilding?

Of course, anytime there is a massive uprising and social transformation, there are challenges. A few questions are top of mind. Given that all aspects of government have been corrupted under Hasina’s regime, each governing institution needs to be reconstituted with new leaders – how do we acquire the skilled leadership needed to lead the new Bangladesh? Many in Bangladesh are still struggling for economic opportunity. How does Bangladesh chart an alternative economic path under global capitalism? The judiciary has been biased and used to suppress dissent. How can an independent judiciary be established? Finally, society has lived in a culture of fear, where civil society organizations and activists were targeted. How can a culture of freedom and democracy be established after years of an autocratic regime? All aspects of society have been impacted by Hasina’s regime, and the challenges are to rebuild Bangladesh.

The task ahead of Bangladesh will be difficult. How do you take the democratic aspirations from the movement and translate them into institutions and chart a path for alternative economic development? This leads to some interesting questions about constitutionalism after a revolution. Most constitutional governments are based on popular sovereignty—the constitution reflects and memorializes the will of the people. By extension, when a revolution or uprising occurs, it requires a new constitution because the relationship between the people and the state has been fundamentally altered. You can’t rely on the old constitution under which Sheikh Hasina was allegedly elected in January, but you need some sort of governing principles to guide the new elections. I believe the current interim government may be leaning on a top-down constitutional process, versus one that I and others have advocated for, a more grassroots constitutionalism to gain input from the people as to what they would like to see in their constitution. This is a People’s Movement. We should have a People’s Constitution.

And to be pragmatic, maybe we won’t get everything we want. Maybe Bangladesh will move from autocracy to some form of friendlier neoliberal democracy. Consider countries that follow a more left political and economic approach. Is it possible, within the totalizing force of global capitalism, to pursue alternative forms of economic development and political organization? I think there are incremental steps that can be taken. These are important questions that Bangladesh is going to have to answer. I am firmly committed to a Bangladesh that is socially, politically, and economically beneficial for all Bangladeshis.

There are signs that are hopeful, but there are also signs that worry me. The current interim government has returned to the IMF for loans, which raises the question: are we going back to the old system? It seeks the approval of the United States in ways that I think should be more neutral. In the 1970s, when Bangladesh became independent, many of those in authority argued for a system of self-reliance. But that changed very quickly. Is it still possible to maintain that self-reliance? Additionally, as mentioned earlier, we see geopolitical pressure mounting from India. Giving Bangladesh support at this moment will be key to demonstrating that a new world is possible.

Ultimately, the fact that mass mobilization forced an autocratic leader to resign is momentous. Historically, when has that happened? People point to the Bolshevik or French Revolutions, and Bangladesh, in my opinion, is the strongest modern-day example of a people’s revolution. This is a huge moment, and moving forward, even if the institutions they are building aren’t perfect, the students will never go back to business as usual. If we don’t like the institutions that emerge, we can continue to evolve them because democracy is a dynamic, evolving process. It’s not something you achieve and then just sit back. We have to be constantly engaged in the work of democracy building.

The uprising comes at a time in which protests have broken out across the world for other causes, most prominently against the ongoing siege on Gaza. Are there lessons these movements can take away from the uprising in Bangladesh?

The world can learn so much from what’s happening in Bangladesh right now. The students’ level of political sophistication is impressive. Each step they have taken has been intentional and strategic, grounded in history.

One of the most impressive things about the student movement is how nationally organized they were; they had nine national coordinators across the country who were all mobilizing around the same set of demands. They were fully aware of earlier movements and why they failed. And they learned from these movements, like the 2018 quota reform, and changed their strategy and practices. For example, the students knew they couldn’t succeed without the involvement of workers. They built ties with unions, particularly the garment worker unions, as the movement evolved. This unity is what made the movement successful, as it appealed to a wide section of society.

The students also understood the ways movements can be divided. They knew that Sheikh Hasina and her regime would try to create class divisions – casting the students as lazy and wanting prestigious civil service jobs. But, the students anticipated this and intentionally organized across different groups to ensure the movement was not reflective of only urban elites. The students’ ability to overcome external forces’ attempts at division shows how important it is for movements to ground themselves in political education. All movements need to understand history and the current political and economic moment to craft an effective mobilization strategy.

Global capitalism is always evolving and expanding, and it’s important to recognize that capitalism today is different from what it was in 1971. In my scholarship, I discuss how neocolonial globalization is localized through nation-state policies. We see this in the case of Bangladesh, where Sheikh Hasina’s economic policy doubled down on efforts to attract foreign investors by creating economic zones, which ultimately increased the economic precarity of the poor and workers. We need to understand how capitalism operates with our laws and policies in different contexts, whether in Bangladesh or the United States. If we are not able to articulate these differences as part of our political-economic analysis, we will miss out on the lessons that are critical for movements to succeed.

Do you see similarities between the student movement for Gaza and the student movement in Bangladesh?

When Sheikh Hasina fled her official residence, it was overtaken by protestors. Two flags were drawn at her house once it was vacated. One was, of course, the flag of Bangladesh, and the other, the flag of Palestine. The struggle in Bangladesh has a different backdrop than the movement for Gaza – the former is centered on an internal struggle for democracy and greater economic opportunity, while the latter on fighting occupation and colonialism. But both movements at their core are fighting for self-determination and the ability of the people to decide their own political and economic future.

There are other synergies between these two movements. First, there is inherent power in the youth and their ability to organize. The Bangladesh uprising has been called the Gen Z Revolution. There is so much negative critique around young people – that they don’t do much and are apathetic, among other things – but I think the student movements in Bangladesh and the United States are unyielding in their conviction.

Both movements also have clear demands and the ability to evolve them. In Bangladesh, the students quickly moved from nine demands to one as state violence escalated to unfathomable levels. With the student movement for Palestine, we first saw calls for a ceasefire and divestment, and we now see the conversation shifting to an arms embargo as a ceasefire no longer is enough.

This evolution had an impact in Bangladesh, and it will have an impact here in the United States. There is a U.S. election coming up. A large swath of voters, including Muslims, anti-Zionist Jewish individuals, and the youth – are saying that they cannot vote for a candidate who funds a genocide. To date, the Democratic Party has been unwilling to take a position and seems willing to risk losing a major portion of the electorate that cannot tolerate America’s continued involvement in genocide. But instead of taking these views into account, the party’s response has been “How can you protest me? Do you want Trump to win?” We saw a similar sort of arrogance in Sheikh Hasina’s administration’s response to the protestors. And these same protestors subsequently completely rejected the two-party binary that existed in Bangladesh and are now reconstituting new parties of their own.

This moment reminds me of a piece by W.E.B Dubois, I Won’t Vote. We are undoubtedly in an important political moment in the United States, and the U.S. movement should learn from Bangladesh. When people say the issue of Palestine is disconnected from democracy – I think that is entirely wrong. Of course, the movement is first and foremost about Palestinian liberation. But also, it represents a referendum on U.S. democracy – what do you want your government to look like? Do you want our taxpayer dollars to fund a genocide? Or are we committed to ensuring these resources go towards health insurance, guaranteed income, housing, and more? Just like the students in Bangladesh, we in the United States are being asked: what kind of democracy do we want?

And one thing for all movements to remember – you are making a long-term commitment to liberation. There sometimes is a sense that you want things to happen immediately. To really be a part of movement work, you have to be deeply committed to understanding that change takes time. I could not have fully imagined how the student movement in Bangladesh would evolve even as I was in Bangladesh in July of 2024. I would have never imagined that within my lifetime Palestine would be a national issue in the United States. And now, it is an issue that I think could decide the U.S. Presidency.

Electoral politics are not the end-all, be-all of any movement. One of the student organizers in Bangladesh said something that stuck with me – she said with any revolution, there will always be a counterrevolution and backlash. We know this from history, and we need to prepare for it. We need to sustain, escalate, and not give up. And we need to understand the global political and economic ecosystem that we are a part of. If we can commit to building this understanding, to learning from our failures, and to sustaining – another world might be possible.