Early investigations into the rise of neoliberalism tended to emphasize the right-wing, libertarian variant, enshrined philosophically in the Mont Pelerin Society, legally in law-and-economics, and politically by conservatives like Reagan and Thatcher. Recently, however, historians and sociologists have turned their attention to the neoliberal turn within center-left parties. For example, beginning in the 1970s, Democrats moved away from their traditional emphasis on New Deal policies towards a more market-friendly, business-friendly agenda. Relative to the Republican move in the same direction, this shift was tempered by a willingness to use tax-and-transfer policies, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, to “compensate the losers” resulting from the embrace of free-trade and deregulation. Nevertheless, the Democratic party’s turn toward redistributive policies marked a stark departure from their earlier commitment to “predistribution” policies focused on the labor market, such as minimum wage laws, pro-union policies, protectionist trade policies, and public employment.

This evolution on economic policy, some historians have suggested, helps explain the changing relationship between education and partisan identity—what Thomas Piketty has termed the “Brahmification of the left.” In our new paper, “Compensate the Losers,” we build on this work by examining in a more quantitative fashion whether this pivot on economic policy can help explain the Democratic Party’s loss of “less-educated” voters.

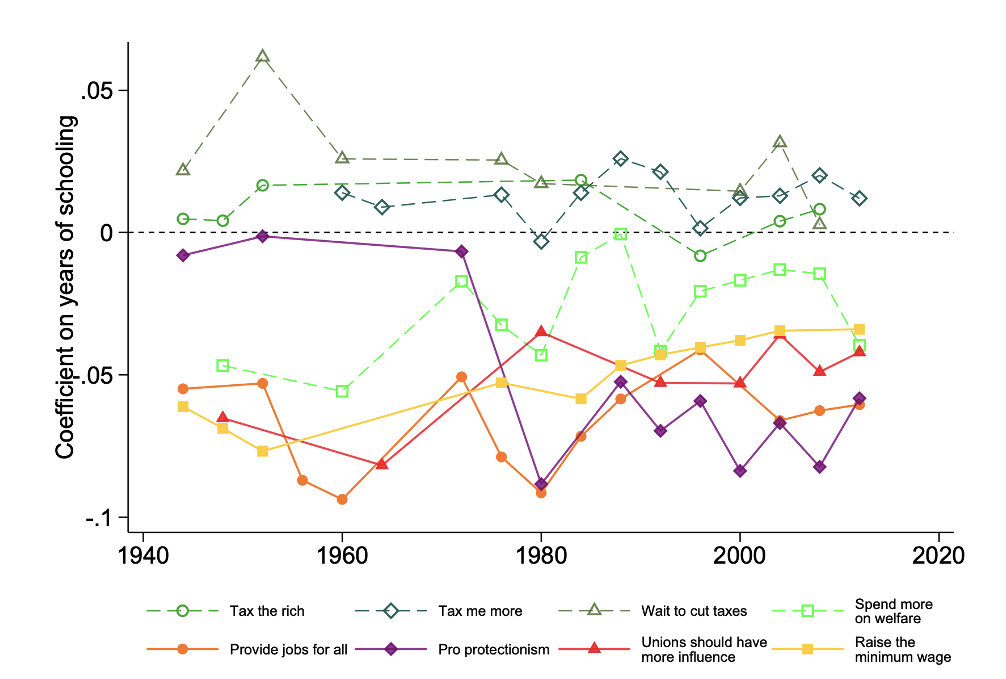

Specifically, when it comes to distributional policies, we find that less-educated individuals prefer “predistribution” policies. The divide by education on these policies—with the less educated much more strongly in favor than the more educated—is large and for the most part unchanged during the past 80 years. By contrast, support for redistribution policies exhibits no similar education gap, and, in fact, we often find greater support for such policies among more educated voters.

Figure 1: Preferences for pre- and re-distribution by education

Note: This graph shows the coefficients of a linear regression of policy preferences on respondent’s years of schooling. In 1945, an additional year of education was associated with a decline in the probability to be in favor of “providing jobs for all” by 5% of a standard deviation; this relationship has stayed mostly constant until today. In contrast, an additional year of schooling has been associated with an increase in the probability to support “taxing the rich” by about 1% of a standard deviation.

While Democrats of the New Deal Era promoted many predistributionist policies — the 1935 Wagner Act legalized and promoted organized labor, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act introduced a federal minimum wage, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other Democrats created the Works Progress Administration and other federal employment programs to maintain full employment — we document that the Democrats moved away from these ideas beginning in the 1970s. Before the 1970s, predistribution-related topics accounted for nearly 20% of House votes in years the Democrats controlled the Speakership, at which point it steadily declined to only 10% by the early 1990s. In comparison, the redistribution share has held steady. Using natural language processing techniques, we find a similar 1970s-era decline in pre- versus re-distributionist language in Democratic Party platforms.

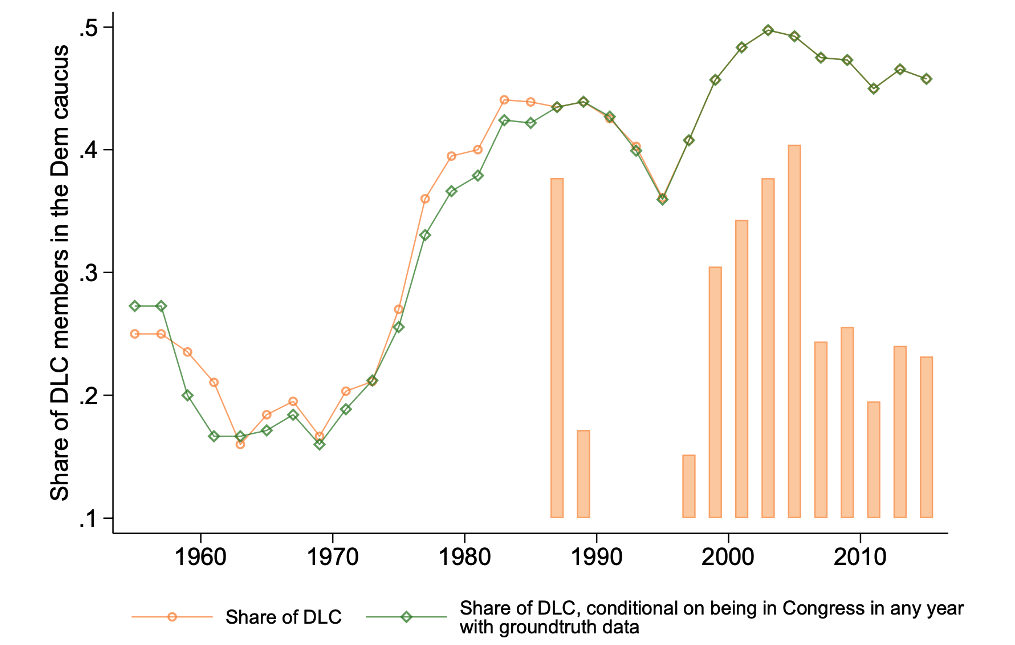

This shift away from predistribution policies in the 1970s coincided with the rise of a faction within the Democratic Party that called themselves the “New Democrats” and who would eventually form a more official organization called the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), as depicted in Figure 2. We analyze vote patterns to show that this faction was generally more conservative than other Democrats but especially so on predistribution topics.

Figure 2: Evolution of Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) membership in Congress

Note: This graph shows the evolution of the proportion of the House Democratic caucus belonging to the Democratic Leadership Council.

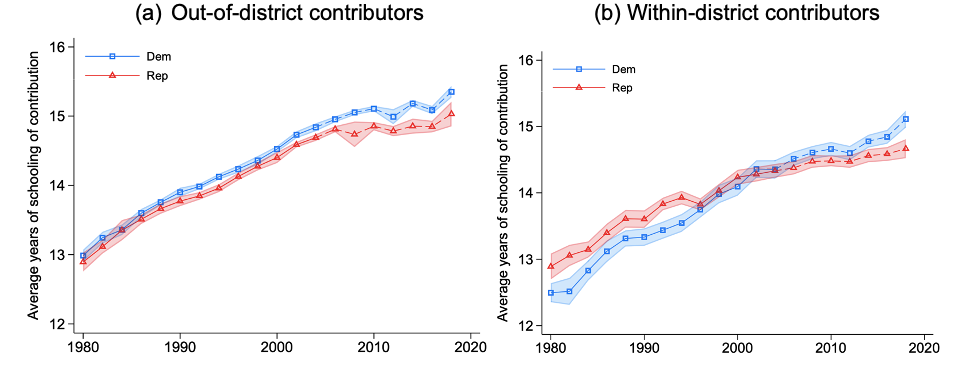

Our analysis suggests that the emergence of the New Democrats can be partially attributed to the growing influence of educated donors in Democratic primary races, in contrast to their role in Republican primaries. This shift is partly due to reforms of the Federal Election Commission (as well as party reforms) in the 1970s, which reduced the political influence of labor unions. Specifically, our findings highlight an increase in donations from educated individuals residing outside the electoral districts during Democratic primaries. This trend indicates that individuals who were ineligible to vote in these races nonetheless exerted significant influence on the selection of Democratic candidates for general elections. Consequently, it is logical to infer that these candidates are more likely to resonate with educated voters in the broader electorate.

Figure 3: Average level of schooling of primary election contributors for House elections

Note: These graphs show the average education level of Primary contributors. The left-hand side graph shows the average education of out-of-district contributors while the right-hand side shows the within contributors.

While detailed records of donations have only been accessible since 1979, the evolving dynamics of the political parties become apparent through an analysis of the backgrounds of Congress members. In the years following World War II, members of the Republican Party were more often graduates of Ivy League institutions. This trend has since reversed, with Democrats now more likely to have attended Ivy League Universities, a shift that became noticeable in the 1970s. Concurrently, during this period, the linguistic complexity of Congressional speeches by Democrats increased, indicating a level of discourse that presumes a higher educational attainment among its audience, compared to that of their Republican counterparts.

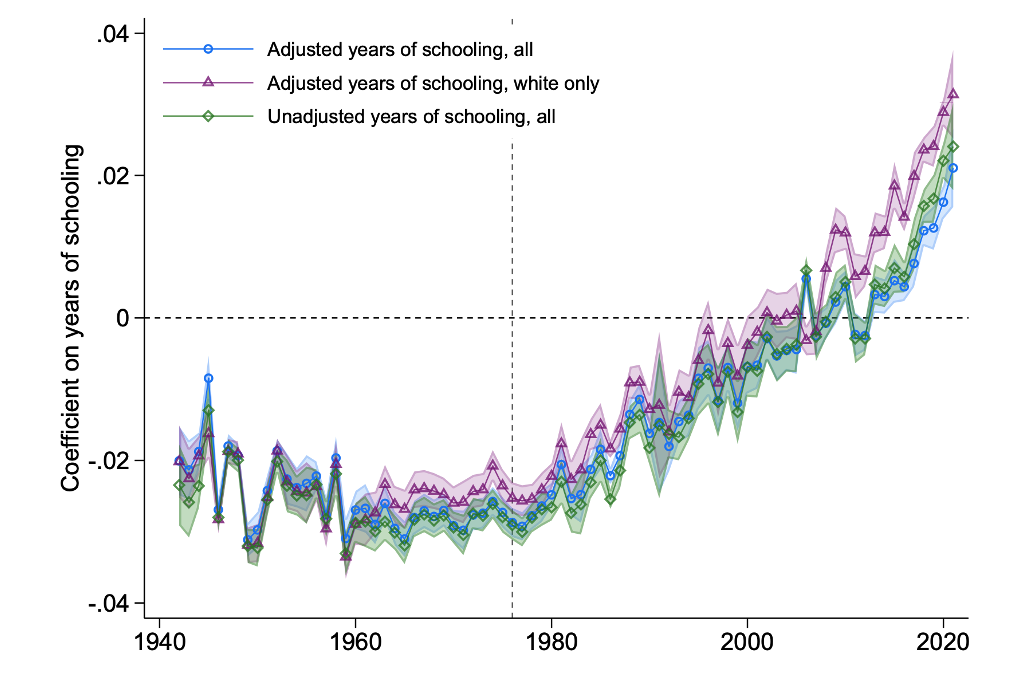

Finally, we study how voters have reacted to this change in the Democratic party. By harmonizing more than 800 surveys, we show that the educational gradient in party identification has been quite stable until an inflection point in 1976 (Figure 4). Since then, the educational gradient in Democratic partisanship has been on a constant rise. Prior to 1976, every additional year of education predicted a three percentage point decrease in the likelihood of identifying as a Democrat. The exact opposite is true today—every additional year of education predicts almost a three percentage point increase in the likelihood of identifying as a Democrat.

Figure 4: Democratic Party Affiliation as a function of education

Note: This graph shows the coefficient of a linear regression of Democratic identification on years of schooling. Until 1976, an additional year of schooling was associated with about a 2.5 percentage points decline in the probability to identify as Democrat. It started to increase in 1976 and today, each additional year of schooling is associated with an increase in the probability to identify as Democrat by about 2.5 percentage points.

We then provide evidence that less-educated voters, the traditional base of the Democratic Party, differentially opposed the New Democrat faction. Through the examination of hypothetical candidate matchups, we show that voters with less education were more likely to say they would vote for Republican presidential candidates when they were facing New Democrat candidates, such as Jimmy Carter, Gary Hart, or Bill Clinton, as opposed to Old Democrat candidates like Ted Kennedy, Jesse Jackson, or Walter Mondale. We also analyze voting patterns in House elections, showing that neighborhoods with lower educational attainment were less likely to support Democratic candidates if they were affiliated with the Democratic Leadership Council.

Obviously, the shift within the Democratic Party’s base during this period cannot be only attributed to changes in their economic policy positions; numerous other factors have played a role in this realignment, which we discuss in detail in our paper. Specifically, we challenge the notion that social issues have been the sole driver for this shift since the 1970s. One key piece of evidence we present is that the Democrats’ progressively liberal views on Civil Rights starting from the 1940s have resulted in the loss of more-educated white Southern voters, not those with less education.

Second, our survey data shows that better-educated Democratic voters tend to be more liberal on social issues. But the DLC Democrats were more socially conservative. That more-educated voters found them differentially attractive suggests it was their conservative economic positions (especially on pre-distribution) that drove realignment, and that educated voters supported the DLC in spite of their social positions.

In summary, we argue that the Democratic Party’s economic policy shifts have played a significant role in the partisan realignment that has occurred in the United States over the past few decades. Indeed, we find that roughly half of the party’s realignment toward better-educated voters can be attributed to voters’ perceptions of the party’ economic policies. One important upshot of this work—and perhaps one reason it is been underappreciated to date—is that voters draw important distinctions between policies that might appear similar in terms of their effects on economic inequality. While law and economics scholars, such as Kaplow and Shavell, have argued that law and policy should be conducted with the aim of maximizing aggregate efficiency, with egalitarian concerns relegated to the tax and transfer system, parties that take this message to heart should not be surprised if they lose less-educated, working-class voters.