In creating franchising, brands like McDonald’s, Jiffy Lube, and Dunkin’ Donuts developed a legal structure that hoards rents at corporate headquarters, by maximizing the flows of income to the brand while blocking participants in production from making claims on them. In my recent JLPE article, I describe in detail how franchisors deploy trademark and antitrust law to leverage market power in product markets into power over independent franchisees and frontline workers. In particular, franchising allows brands to control working conditions for workers they do not directly employ—allowing them to outsource an employer’s legal duties and responsibilities to legally separate franchisees—while excluding both franchisees and workers from larger shares of product market or other rents.

At the center of the franchise model are legal mechanisms known as vertical restraints, contractual restrictions on the competitive decisions of separate firms or individuals. Common vertical restraints include maximum prices, which forbid franchisees from raising prices above a certain level, and non-compete clauses, which prevent franchisees from finding alternative employment or starting a new business once the contract ends. Such restraints allow firms to use the legal boundaries of the firm as instruments of exclusion: while direct employees of firms have a kind of corporate citizenship that gives them some power to make claims on the resources and revenues of the firm, workers at legally distinct firms encounter the boundaries of the firm as barriers of exclusion.

However, vertical restraints do more than simply exclude. Restraints in franchise contracts also serve to disempower both franchisees and workers by reducing their bargaining positions and limiting their options, inducing them to increase flows of income to the franchisor. In particular, as I explain below, current trademark and antitrust law allows franchisor firms to obtain the low wages and intense, deskilled work processes they desire, without incurring the risks and duties of an employer.

Franchising’s Three Levels of Power

Franchising is a business structure in which one firm, which owns a trademarked brand, licenses another, legally distinct firm to operate local establishments under its brand name, rather than own and operate those units itself. Rather than use ownership to control activity and enforce uniformity, franchisor firms rely on vertical restraints. Franchising is a prominent example of a “fissured workplace,” in which workers are not directly employed by the “lead” firm that actually controls their working conditions, but rather are hired through networks of contractors or franchisees. As I show in earlier work, powerful franchising firms deliberately created fissured workplaces through a concerted effort of lobbying and litigation to win broad antitrust tolerance for vertical restraints, gaining vertical integration-like control over business units without the corresponding duties and responsibilities to workers.

In order to understand franchisor power, it helps to understand short-side power, a kind of power over quantities of a scarce good. When there are queues of people lining up for a job, a loan, or a franchise license, the neoclassical notion of market-clearing harmony obviously does not suffice. One side of the market is able to pick and choose with whom it will transact, while the other side contains individuals who fail to transact even while they are willing to offer the same terms as those that do.

In general, those on the “short side” of a non-clearing market—the side where the number of desired transactions is least—have power over those queueing up on the “long side,” because the former can offer the latter a rent: a payment above their next-best alternative or “outside option.” (While the term rent has a pejorative meaning elsewhere, here all it means is a premium over one’s next-best alternative, with no connotations of ethical desert.) This kind of rent is called an enforcement rent, because the threat of withdrawing it gives the party on the short side power over the party on the long side. To see how this works, consider a labor market. It is much more costly for a long-side worker to lose a job than for a short-side boss to lose a worker. By offering a “rent”—a wage slightly above the workers outside option should they be fired—employers give themselves power over workers.

Bosses don’t want this power for its own sake, they want it for its ability to get workers to do things they otherwise wouldn’t do. We call bosses and other parties on the short side “principals” because the enforcement rent gives them the power to get the party on the long side (the “agent”) to carry out activities on their behalf. Employers, as the principals in labor markets, use the threat of firing to motivate employees, their agents, to work diligently in furtherance of the employer’s interests. Meanwhile, the presence of individuals who are “quantity-constrained”—for example, the reserve army of unemployed workers who would like a job at the going wage rate but are unable to obtain one—disciplines the bargaining demands of the workers who are currently employed.

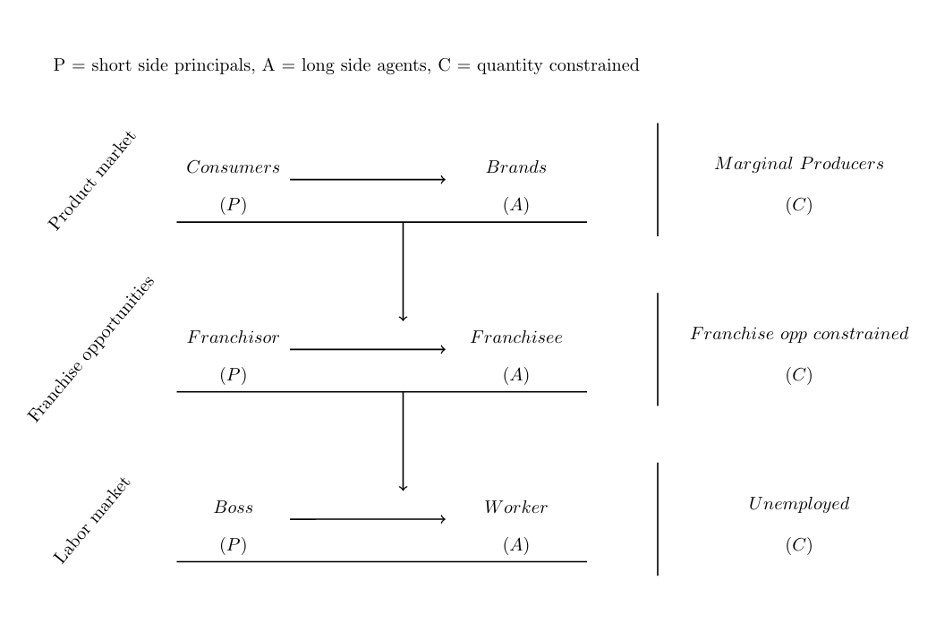

Franchising has three levels of such non-clearing, power-laden markets: product markets, the market for franchise opportunities, and the labor market. Figure 1 depicts these three levels and their interlinkages (adapted from a model of linked credit and labor markets found here). Starting at the top, franchising, in which a firm licenses its valuable brand to others, is largely a creation of trademark law. State-granted trademarks, combined with consumer preferences for branded products, allow brand owners like Dunkin’ Donuts to garner rents in the product market. (While customers on the short side of the product market collectively have a degree short-side power over brands, they face enormous collective action problems preventing them from strategically using it).

One level down from the product market is the middle level, the market for franchise opportunities. The brand in the top level, Dunkin’ Donuts, is the franchisor in the middle level. Some of the quantity-constrained marginal entrepreneurs in the first level, unable to develop a valuable trademark and effectively compete with branded chains, may give up and resign themselves to joining a branded chain as franchisees. This story of frustrated entrepreneurship is in fact a common refrain from franchisees. As a Dunkin’ Donuts franchisee named Richard Riggs explained his decision to sign a contract he knew was unfair to a Congressional committee, “I had the choice of going with a franchisor or opening up Riggs Donut Shop on the corner and competing with the franchisor.” The difficulty of competing without a brand name is well-documented: McDonald’s famously put the original McDonald’s brothers restaurant out of business after it acquired the brand name from them. Trademarked brands can thus offer these would-be entrepreneurs access to a share of their product market rents as an enforcement rent if the latter agree to subordinate themselves to the brand rather than stay independent.

Finally, in the bottom level, franchisees from the middle level are the bosses in labor markets, where they hire production workers. The existence of involuntary unemployment means franchisees are able to offer rents, however small, to make it costly for workers to lose their jobs, inducing workers to exert high effort levels. In this way, power flows downward from the product market: brand-franchisors have power over franchisee-bosses, who in turn have power over workers.

Principals and Agents

The economics literature interprets franchising in terms of what are known as “principal-agent models.” In such models, franchising is portrayed an efficient solution to a conflict of interest between brand owners and local managers. Managers have incentives to slack off or pursue other self-interested activities in conflict with the goals of the brand owner. Franchise contracts supposedly resolve these conflicts by relying on “independent” franchisees instead of salaried managers. Instead of receiving a flat salary, franchisees keep store-level profits after paying a royalty. Franchisees directly profit from their own effort. Since the managers now have “residual claimancy” or “skin in the game,” their incentives are aligned with those of brand owners, increasing franchisee effort levels and generating higher incomes for both parties. Vertical restraints and enforcement rents, meanwhile, internalize any remaining externalities arising from franchisees’ ability to “free ride” on the brand name.

However, unlike the interlocking three-level principal-agent relationships discussed above, mainstream economic models tend to consider the middle level only, and treat franchisees as if they are the direct producers of the store’s output. But they are not. They supervise the workers that produce this output. So we have a second principal-agent problem to consider. In the boss-worker principal-agent relationships, workers do not directly benefit from their effort and do not have skin in the game. They are paid a fixed hourly wage, and rather than being incentivized by residual claimancy, they are are monitored by bosses under threat of termination to make sure they don’t slack off. Since they are not residual claimants, workers’ ability to garner higher wages depends on their power to command enforcement rents. The next section shows how commonly used vertical restraints take away workers’ ability to do this.

Vertical Restraints

Enforcement rents are effective in inducing effort because franchisees and workers set their effort levels as a function of the size of the enforcement rent—that is, based on the gap between the income they can expect from entering a given contract and their next-best alternative (or “outside option”), should their contract be terminated. Vertical restraints allow franchisors to extract extra effort from both franchisees and workers for any given level of enforcement rent. Some vertical restraints lower the value of franchisees’ outside options, increasing the power of the threat of termination. These restraints include:

- Non-compete clauses, which prevent franchisees from finding alternative employment or starting a new business once the contract ends.

- Forum selection clauses, which force franchisees to travel to the home jurisdiction of the franchisor in any litigation, dramatically raising the cost of challenging the franchisor in court.

- Right of first refusal to any sale of the franchisee’s business, lowering the potential resale value of the franchise assets.

- Individual and spousal guarantee, which gives the franchisor recourse to the franchisee’s personal assets should the franchisee violate the agreement.

- Direct withdrawal from franchisee bank accounts, which limits the franchisee’s ability to accumulate a stronger outside option.

In addition, digital surveillance, such as real-time access to franchisee cash register point-of-sale systems, increases the force of the threat of termination, by making it more likely that a shirking franchisee will be caught and terminated. A more closely monitored franchisee will exert more effort for a given level of enforcement rent.

While the restraints mentioned above reduce the franchisee’s bargaining position, another set of vertical restraints focuses on taking away franchisee discretion, by removing variables from their profit-maximizing choice set:

- No-poaching agreements, which prevent franchisees from hiring each other’s employees.

- Price-fixing, in which the franchisor imposes maximum or minimum prices.

- Mandatory hours of operation, which often force franchisees to operate unprofitable overnight shifts.

- Supplier restrictions, which often place large proportions of a franchisee’s operating costs outside of their own control.

- Finely detailed product and service standards, such as prescribing the precise manner in which employees greet customers.

These discretion-reducing restraints induce franchisees to focus their attention on the remaining variables they can control: labor costs and labor discipline. What these two types of restraints accomplish together is the creation of surveillance and discipline-intensive workplaces. In other words, vertical restraints induce franchisees to work really hard—at the task of keeping labor costs down and working their own employees really hard. As one McDonald’s franchisee reported, the company responded to a complaint about the impact of maximum prices on her profits by telling her to “just pay your employees less.” It is franchisor vertical restraints that create effort-intensive, low-wage workplaces, but franchisors are not legally responsible for the outcome: franchisees are.

Workplace surveillance technologies like computers in cash registers and GPS trackers in trucks reduce wages and increase effort by lowering the value of the enforcement rent bosses have to pay workers. Vertical restraints like those in franchising have the same effect, by incentivizing franchisees to intensively monitor and surveil a low-wage workforce. In an example of refractive surveillance, franchisors use vertical restraints to indirectly surveil and discipline labor through the franchisees they are legally allowed to surveil and discipline, while avoiding liability as joint employers of those workers.

Franchisor power ultimately derives from trademark and antitrust law. Trademarks and vertical restraints facilitate brands leveraging market power in consumer markets into low-wage, high-effort labor workplaces, while allowing those brands to avoid an employer’s corresponding duties and responsibilities to workers. By substituting vertical contracts for direct ownership and employment, franchisees use the legal boundaries of the firm as instruments of exclusion, keeping participants in the production process from accessing a share of product market rents. The end result is siphoning wealth upwards to shareholders in dominant brands. However, none of this is natural: different laws could make it harder to exercise the power securing streams of wealth upwards, and easier for workers to reverse the flow.