When I entered law school in 1999, I was primarily interested in two things: HIV/AIDS, and critical approaches to human rights. I was also young and queer, and Bowers v. Hardwick was the law of the land. Sodomy was illegal in many states, and so, it seemed, was I. So, I was also deeply interested in the law of sexuality.

I ended up teaching and writing about intellectual property (IP) law. My 1L self would not have believed it. (I even have the picture to prove it).

As a prelude to a series of future posts about my work in this field, I wanted to describe how I came to IP law – or rather, how it came to me. If you aren’t sure what IP means or why it is important to social justice today, this post is for you. The same is true if you are wondering how someone interested in law and political economy develops a research agenda, and why someone might choose patent law as a key part of it.

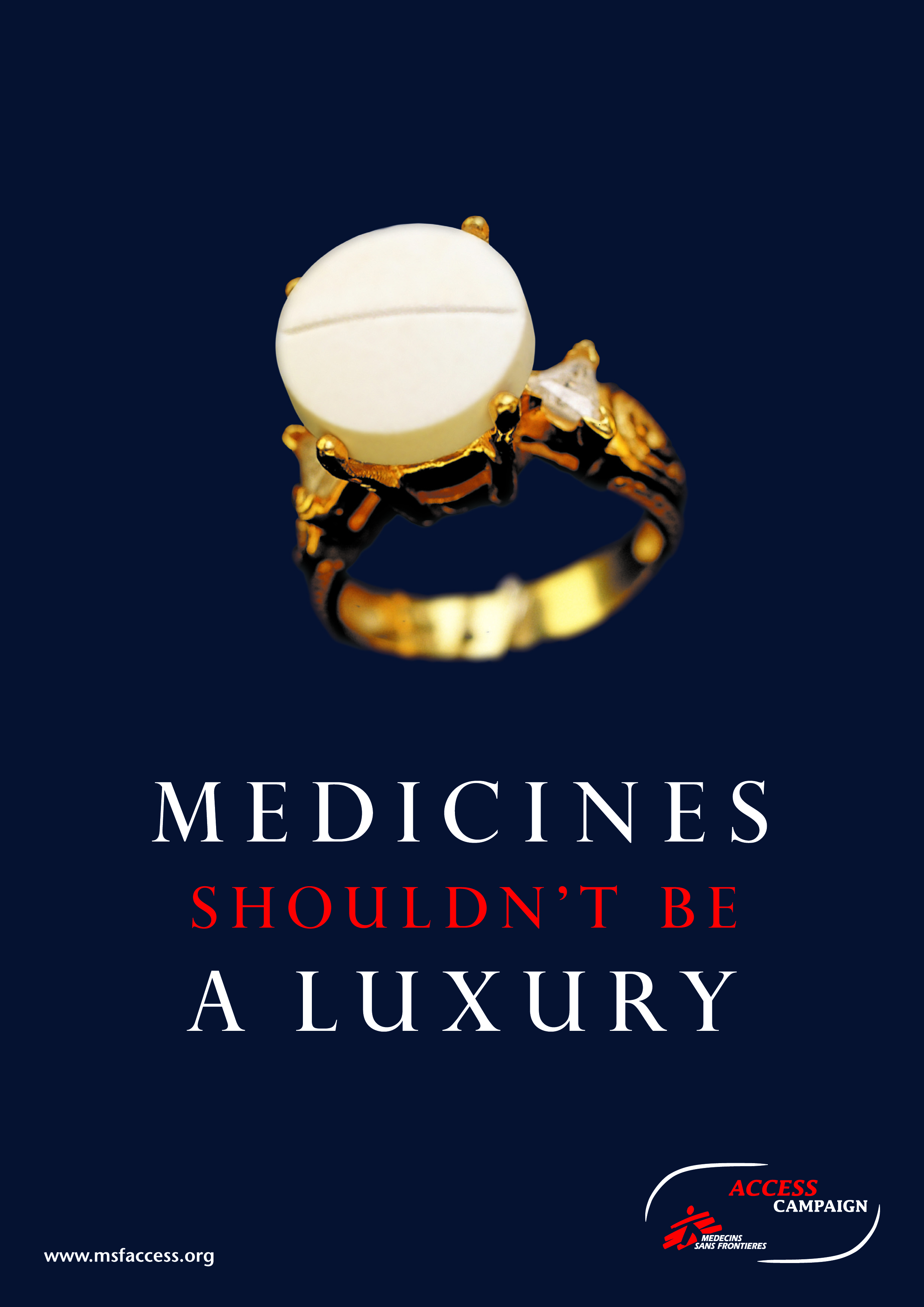

Back in 1999, the global HIV/AIDS pandemic was burning like a gasoline-driven fire. Twenty-seven million people around the world were living with HIV/AIDS, and three million more were newly infected each year. The highest prevalence was in sub-Saharan Africa, where in some places – like newly liberated South Africa – one in every five adults was HIV-positive. For me, HIV also felt deeply personal. The gay community in London, where I lived for a few years before law school, was profoundly shaped by the virus. But it also had been reshaped by new anti-retroviral drugs. In 1996, those drugs were introduced in wealthy countries, and AIDS-related deaths started to fall precipitously. But in the rest of the world, almost no one had access to these medicines. They were far too expensive – $10,000 per person per year, in a time and place when annual health expenditures could be as low as around $10 per person per year.

I had learned all this in my first real job – a half-time administrative position working for an HIV/AIDS organization in London. When I learned about the new drugs, I thought that they were expensive because they were sophisticated, and hard to make.

But then AIDS activists in London and New York and South Africa taught me about patents.

HIV drugs were expensive, it turns out, not because they were costly to make, but because companies could set their prices at whatever they liked. And that, in turn, was because governments had granted these companies monopolies. (Patents are government-granted exclusive rights that allow an inventor to prevent anyone else from making, using, importing, or selling their invention for twenty years. For more on the nature and evolution of patent law, copyright law, and trademark law, see Terry Fisher’s wonderful history of the ownership of ideas in the US.)

Copies of HIV medicines could be made far more cheaply – today at less than $100 per person per year – if countries developed legal strategies that could overcome the patent barriers. And this is exactly what the AIDS and access to medicines advocates that I was learning from were doing: finding avenues to use generic drugs that were legal, within the confines of domestic and international law. (The WTO plays a big role in this story, both past and present.) Along the way, the access to medicines movement profoundly changed the shape of the epidemic. While much remains to be done, today there are 19.5 million people around the world receiving anti-retroviral therapy. That number was 685,000 in 2000.

It was this realization – that medicines could be cheap enough to provide life-saving care to millions of people, but only if you understood something about patent law – that drew me to work on IP. It was a few more years before I would think of the issues as broader in nature.

Intellectual property isn’t interesting just because it affects the price of medicines. It is interesting because there are structural reasons that IP came to AIDS activists – and that it at the same time came to food and farming activists, to free culture activists, to artists, to disability rights activists, and to advocates for education.

IP law, it turns out, has been expanding dramatically in recent years. This reflects underlying economic dynamics, but also ideational and political forces.

As we have shifted from the industrial age to what Manuel Castells has influentially named the “informational age,” information processing has become more important to our economy. Where companies can claim monopoly rights to information, they can become extraordinarily profitable – this is the story of the drug industry, but also Hollywood, Monsanto, and the highly concentrated publishing industry. IP-based industries lobbied hard over the past few decades for expanded IP rights, and often obtained them. The TRIPS Agreement is the most powerful example. But the story is not a deterministic one, where economic changes led mechanically to expansions in law. There were lots of possible responses, and it is not obvious that the one we’ve chosen was the best one for industry, much less for the rest of us. Ideas mattered enormously to the expansion of IP as well. (Fisher is excellent on this. I’ve written about this too, in an article that describes the role of conceptual frames in both the expansion of IP and the recent counter-mobilization.)

This is important. Mechanistic accounts that treat law as the natural outgrowth of market forces tend to suggest that there’s little that can be done to intervene. But law does not naturally follow from economic forces. Law is instead a place where we argue about how we should order our economy. And it was this realization that made me want not just to advocate for changes to IP law, but also to study how arguments in its favor had been constructed, and could be altered.

In sum, it’s worth attending to IP law today for at least three reasons. First, it is emerging as a key influence on both our economy and our society. It sets the terms of access to (and development of) all kinds of things that matter to our politics, our society, and our individual life chances. It also defines – indeed, creates – one of the most important sources of capital in contemporary life. Patents, copyrights, and trademarks are the deeds to the property of the informational age.

Second, IP also plays an important role in the shape of inequality around the world today. And because information is so profoundly sharable, it may also be an important place to go to redress inequality. (More on this later, but you can find some of my incipient thoughts here.)

Third, the field is a terrific example of the overall problem that law and political economy scholars try to address. IP has for many years been dominated by efficiency talk – indeed, it is economics itself that allows us to talk about something called “IP.” A few decades ago, we would have instead talked about copyright, patent, and trademark law as distinct fields. They still are – entirely – but they’re often conjoined in courses on “IP.” They are all considered species of “exclusive rights in information,” created in response to public goods problems and the need for market-led innovation. IP is a great place, then, to get inside of concepts like efficiency, and to reveal their fundamentally political nature. It’s a great place to trace the contribution of ideas – for example, the neoliberal picture of the state – to the reification of immaterial property. (Like real property, but even more obviously so, this kind of property is clearly not a “thing,” although it is often treated as one.) To rebuild this area of law, we need accounts that can break down and find the seams in the dominant account of the field. But we also need to develop an account of the values beyond efficiency that should underpin this field. And we need to identify how changes in this area of law can help make our world more fair, equal, and democratic. Much of the academic work I do is in this vein. I look forward to sharing more about it in the coming weeks.