This post opens a series on LPE & Social Movements.

When members of the Sunrise Movement confronted Senator Dianne Feinstein ten days ago, they demonstrated the renewed vitality of an old force in democratic politics: organized young people bringing bold new visions to complex social problems. In the video, we see the power of movement participants to transform how we think and dream. In times of peril and possibility, radical visions—where the scale of the vision matches the scale of the problems we face—can capture our imagination and change what we think is possible. In this way, social movements galvanize a different kind of force in politics, one of hope and collective action rather than cynicism and alienation.

When members of the Sunrise Movement confronted Senator Dianne Feinstein ten days ago, they demonstrated the renewed vitality of an old force in democratic politics: organized young people bringing bold new visions to complex social problems. In the video, we see the power of movement participants to transform how we think and dream. In times of peril and possibility, radical visions—where the scale of the vision matches the scale of the problems we face—can capture our imagination and change what we think is possible. In this way, social movements galvanize a different kind of force in politics, one of hope and collective action rather than cynicism and alienation.

Left social movements are both a fount of creative law-making and a means by which to hold politicians to account. From the lunch counter sit-ins of the Civil Rights Movement to the Black Panther Party’s and Young Lord Party’s Ten and Thirteen Point Programs, activists have a long history of altering our sense of what is possible, as Aziz Rana recently laid out on this blog. When we pay attention to collective forms of struggle, as Kate Andrias argues, we see how power-shifting and law-making happen from the ground up.

As Bob Hockett recently explained, the Green New Deal is the product of the Sunrise Movement’s recognition that economic injustice and environmental disaster are existential threats to our well-being. By linking issues that are typically seen in policy-making spaces as distinct, the Green New Deal reckons with the clash between human needs and capitalism’s rapacious hunger for land, labor, and resources. Rather than shrink in the face of an immense set of challenges, the Green New Deal rises. It places the transformation of our social, economic, and political order into the realm of possibility.

But it’s not just the Sunrise Movement. A generation of organizers and activists who have come of age post-Occupy are articulating visions for transforming the United States, including the relationship of the state to its constituents, and of human communities to each other and the planet. We should all—politicians, professionals, students, engaged community members—embrace the challenge posed by social movements rather than seek to deflect it, as Feinstein did in the meeting with her young constituents.

For too long, the agendas of politicians on the center-left have been dominated by top-down, expert-driven, single issue forms of lawmaking supported by sporadic popular mobilization. Think of the Center for American Progress or MoveOn.org as the prototypical institutions oriented toward liberal legislative action in the last two decades. This was the approach used by the Obama Administration to pass its two historic legislative achievements, the Affordable Care Act and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. That formula—supported in part by corporate donors to the Democratic Party— tamps down anger with the way things are and prevents people from calling out their enemies in the new American oligarchy. The D.C. “policy-industrial complex” co-opts popular sentiment, demands specific policy proposals, embraces and internalizes public austerity values, and advances their own non-universal half-measures that do not threaten donor interests on Wall Street or in the health insurance and pharmaceutical industries, for example.

But now, with progressives like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayana Pressley, and Rashida Talib in Congress, and the Justice Democrats pushing Congress to the left, we see what is possible when lawmakers seriously consider social movement visions. That is what happened with the Green New Deal: it began with social movement agitation, and moved from there to broader engagement and policy proposals. The Sunrise Movement exemplifies how the political visions of left social movements include blueprints for transformative legal change.

Another powerful example of a transformative legal vision born in social movement spaces comes from the Movement for Black Lives 2016 policy platform, A Vision for Black Lives. The Movement for Black Lives came out of the organizing of young Black people mobilized by George Zimmerman’s killing of Trayvon Martin, and the rebellions in Ferguson and Baltimore, provoked by Darren Wilson’s killing of Michael Brown, and the Baltimore Police Department’s killing of Freddie Gray. Rather than take a narrow frame on the violence of police, the Movement for Black Lives confronts the entrenchment of anti-black racism in the United States. The Vision expands the frame beyond police to a larger set of institutions, from the school-to-prison pipeline to immigrant detention to money bail and reparations. Moreover, it takes an abolitionist approach to reform. The Vision aims to shift power and resources into Black and other marginalized communities and shrink the space of governance now reserved for policing, surveillance, and mass incarceration. For example, a new women’s jail at an unused immigration detention center in Los Angeles County was recently stopped by movement activists and the current men’s jail will be replaced with a mental health facility. A growing number of campaigns across the country exemplify the Vision’s call to divest from police, jails, and prisons, and invest in education, jobs, health care, and more.

Another powerful example of a transformative legal vision born in social movement spaces comes from the Movement for Black Lives 2016 policy platform, A Vision for Black Lives. The Movement for Black Lives came out of the organizing of young Black people mobilized by George Zimmerman’s killing of Trayvon Martin, and the rebellions in Ferguson and Baltimore, provoked by Darren Wilson’s killing of Michael Brown, and the Baltimore Police Department’s killing of Freddie Gray. Rather than take a narrow frame on the violence of police, the Movement for Black Lives confronts the entrenchment of anti-black racism in the United States. The Vision expands the frame beyond police to a larger set of institutions, from the school-to-prison pipeline to immigrant detention to money bail and reparations. Moreover, it takes an abolitionist approach to reform. The Vision aims to shift power and resources into Black and other marginalized communities and shrink the space of governance now reserved for policing, surveillance, and mass incarceration. For example, a new women’s jail at an unused immigration detention center in Los Angeles County was recently stopped by movement activists and the current men’s jail will be replaced with a mental health facility. A growing number of campaigns across the country exemplify the Vision’s call to divest from police, jails, and prisons, and invest in education, jobs, health care, and more.

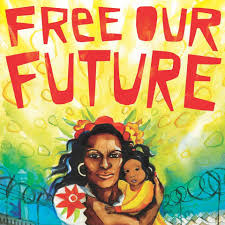

Immigrant justice activists who fought for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA) and against the expansion of a collaborative federal-local immigration enforcement program called Secure Communities provide another example. In frustration and anger with both political parties, youth activists entered the public debate on their own terms, through public expression, collectivity, and solidarity.  Mijente, a leading formation that emerged from this period, recently set out its policy platform entitled Free Our Future. Thinking well beyond the hashtag “AbolishICE” and the recent popular mobilization against family separation, Mijente takes an abolitionist approach to immigration reform, calling for the decriminalization of migration, the end of all forms of immigration detention, and the demilitarization of the border. Consistent with waves of twentieth century suffrage movements, these organizers and activists demonstrate that law-making is not limited to those with formal citizenship and that the polity can expand through confrontation and democratic engagement.

Mijente, a leading formation that emerged from this period, recently set out its policy platform entitled Free Our Future. Thinking well beyond the hashtag “AbolishICE” and the recent popular mobilization against family separation, Mijente takes an abolitionist approach to immigration reform, calling for the decriminalization of migration, the end of all forms of immigration detention, and the demilitarization of the border. Consistent with waves of twentieth century suffrage movements, these organizers and activists demonstrate that law-making is not limited to those with formal citizenship and that the polity can expand through confrontation and democratic engagement.

A third example is that of movement actors working within criminal courthouses to reimagine the meaning of public safety. Consider the work of community bail funds, such as the Chicago Community Bond Fund or the National Bail Out collective. Through the act of posting bail for multiple strangers over time, community bail funds show us a vision of communal support that turns to mechanisms other than caging in jails and prisons. When bail funds free people who then come back to court, as most of them do, they undermine idea that safety is linked to the payment of money bail. Community bail funds represent a radical rejoinder to the claim that incarceration is necessary to protect public safety. In these bottom-up efforts, money bail becomes not just an error-prone system, replaceable by algorithms, but rather a rejection of the criminal legal system’s raced, classed, and gendered violence in the name of public safety. The Chicago Community Bond Fund, for instance, describes itself as “making progress towards a world in which we don’t have to purchase our neighbors’ freedom.”

Policy analysts, lawyers, and professors and other professional experts are involved in supporting these movements. But the energy and direction comes from affected communities coming together to understand the deepest problems that plague us, and to imagine how we might address them in a meaningful and sustainable way. Social movements present an opportunity to reverse power relations between ordinary people and the experts by inviting lawyers work to work for the movement, not the other way around.

Moreover, social movement organizations are attempting to scale up, and in so doing, they are intimately connecting their transformative visions to base-building on the ground. A far cry from expert-driven policy proposals, these movements generate bold initiatives in response to lived reality as they organize larger and larger numbers of the public, increasing the space for collective governance. As reflected in responses to the Green New Deal, movement-generated proposals are often criticized as lacking political viability. But Medicare-for-all and new proposals to tax the very rich show us that the ground is shifting and that political dynamics can change quickly. When left politicians start to channel movement visions, the narrow, rightward-skewed political spectrum in which law-making has occurred in the last 40 years becomes open to genuinely radical ideas for the first time in many decades.

The United States has always operated in a democratic deficit, a country beholden to the powerful few. Renewed social movements on the left, under-resourced and relatively weak in conventional political terms, have the power to create democratic accountability through base-building, contestation, and visioning. As we saw in the encounter with Senator Feinstein, groups of passionate people–particularly young people–working in concert can challenge and transform our politics. We should engage and support them in solidarity.