This post is part of our symposium on the Law and Political Economy of Meat.

The antitrust critique of U.S. agriculture that is dominant in progressive politics is based on a flawed analysis of the farm economy that insists farmers are in dire straits. In her new book, “Break ‘Em Up,” Zephyr Teachout uses the metaphor of “chickenization” to relate the plights of chicken farmers using feed supplied by Tyson to Uber drivers forced to accept rate cuts. In a fiery attack on Joe Biden’s agriculture team last summer, David Dayen argued that corporate middlemen like Cargill and Bayer exert excessive control over the industry and bend farmers to their will. “Some of the biggest Fortune 500 companies may be in agriculture and are making huge profits,” Teachout writes in her book, “but farmers are poor and insecure.”

The antitrust movement is not wrong to focus on the influence of agribusiness corporations. These multinationals have helped transform huge swathes of the globe into biological wastelands, depopulated the countryside, and created a class of hyper-exploited workers. But the standard antitrust analysis overlooks the extent to which farmers benefit from the current system. The vast majority of farmers in the United States are now wealthy, comfortable, and conservative. In this piece, we explain why it is farmworkers, not farmers, who will be at the forefront of any effort to democratize agriculture.

Any analysis of modern farming has to start with the understanding that wealthier farmers won their war against more modest farmers long ago. New Deal planners and Farm Bureau representatives set up the modern farm system to reward large-scale production. As the government increased payments to lift the economy from the Great Depression, large farmers got most of the aid. The number of farm operators fell by 70 percent from 1930 to 1997, as acreage and sales concentrated in fewer hands.

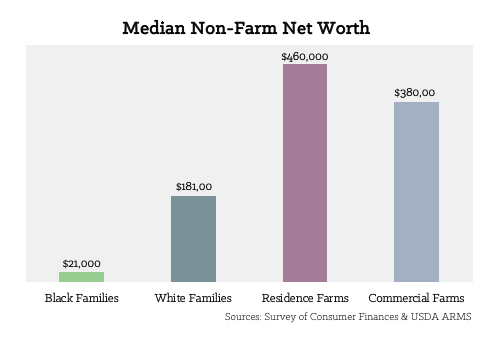

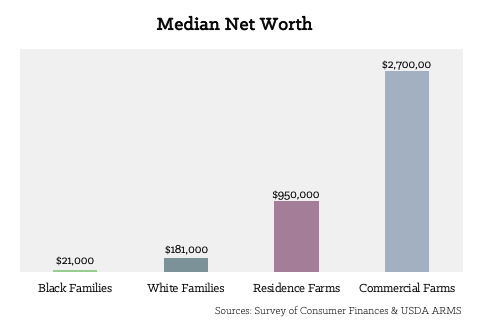

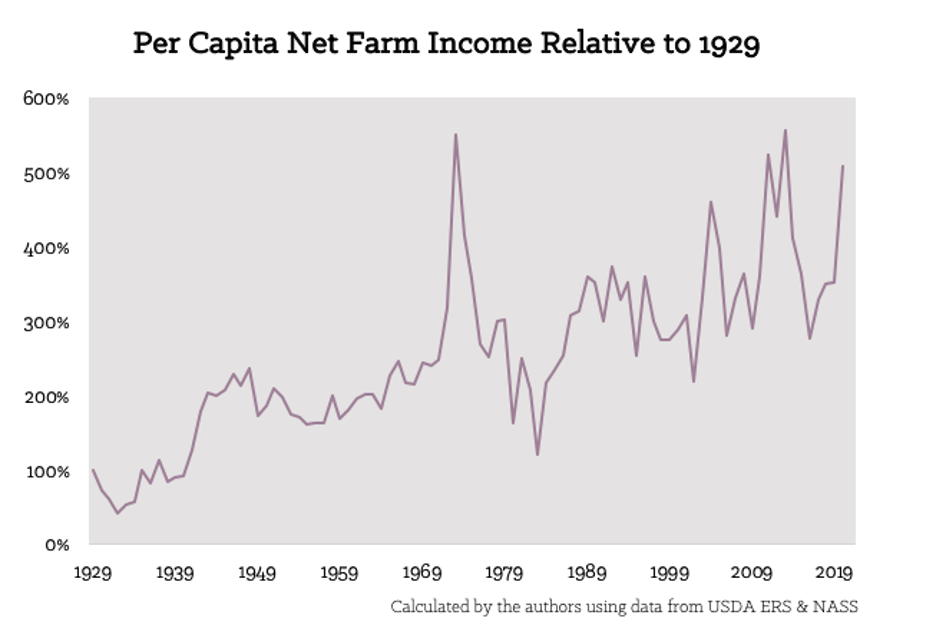

The farmers still around today are, by any measure, wealthy. The median net income for farm households is 21 percent higher than the overall median and goes even further because of lower cost-of-living in rural areas. The statistics for wealth disparities are more extreme. The median farm household has a non-farm net wealth 2.5 times the median household and a total net wealth 9 times as high (both of these figures account for debts). In fact, 97 percent of farm households have higher net wealth than the median American household. The general farm economy is also strong. Despite innumerable reports that use total farm income to argue farmers are in crisis, per capita farm income is near historical highs. Five of the ten best farm income years since the Great Depression have come in the last decade.

How, then, do mainstream antitrust writers produce so much data to suggest that farmers are poor? Most often, they misinterpret aggregate numbers that require a great deal more context. For example, antitrust arguments commonly focus on the fall in the “farmer’s share of the food dollar” from 37 cents in 1980 to 15 cents today. This is true, but total spending on food is up and the number of farms is down. The upshot: farm revenues are near record levels today.

Another common pitfall is the use of summary statistics that are skewed by the Department of Agriculture’s idiosyncratic definition of “farm.” David Dayen, for example, writes that “the USDA estimates that more than half of all farm households are losing money.” But USDA’s Census of Agriculture, the source of many such statistics, includes an enormous number of “farms” whose owners have no interest in farming for profit or even as a hobby. Though the census reports around 2 million agricultural operations, two-thirds of these, per the best available data, are retiree or “lifestyle” farms. Furthermore, the USDA figures include all operations that are simply “capable of producing $1,000 in sales each year.” In fact, almost a quarter of the “farms” in the 2017 census did not sell any farm products whatsoever.

Farm organizations portray low- or zero-sales farms as low-income families struggling to get back into agriculture. In reality, most of these farms are owned by wealthy rural and exurban residents with other financial means. The median household with a “residence” farm—a category that makes up almost all small-scale farms and the majority of all farms—lost $1,600 in farm income in 2019. But these same households, at the median, take in more than $100,000 in total income and hold around $450,000 in net non-farm wealth (about 4 times the median U.S. household). As journalist Maggie Koerth found in an investigative report, most small farmers in the agricultural census “aren’t the farms of the poor; they’re the yards of the upper-middle-class.”

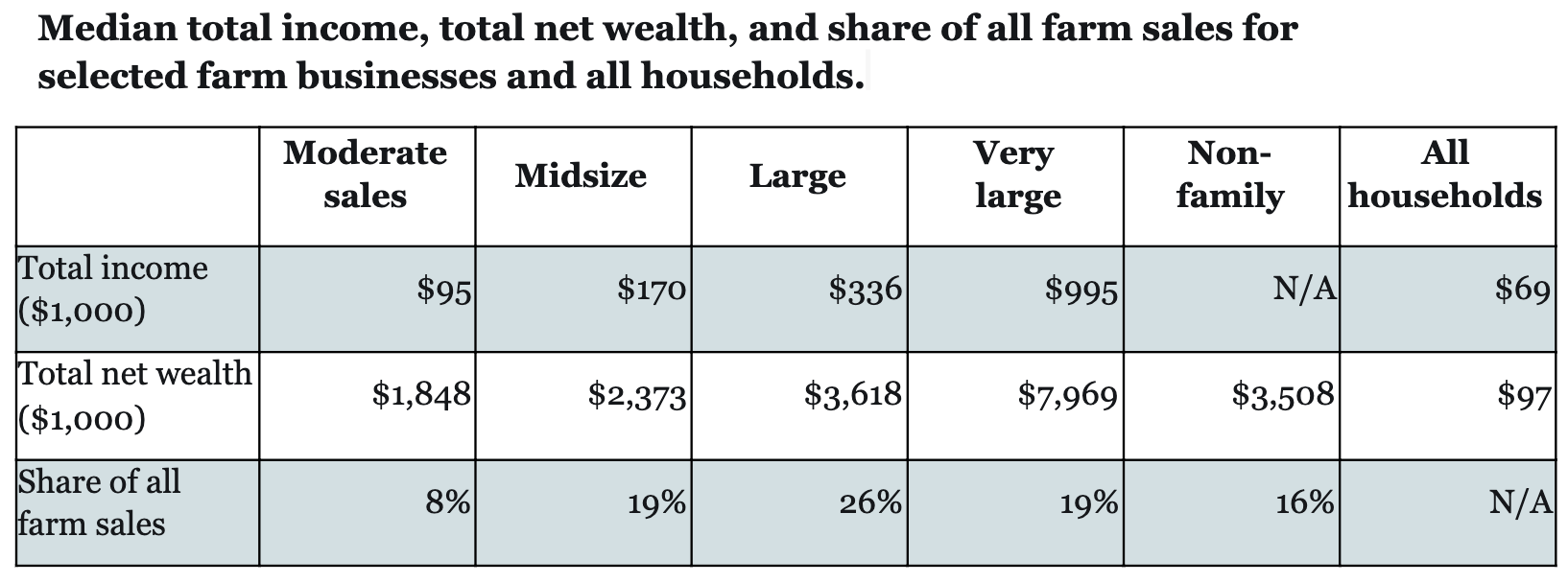

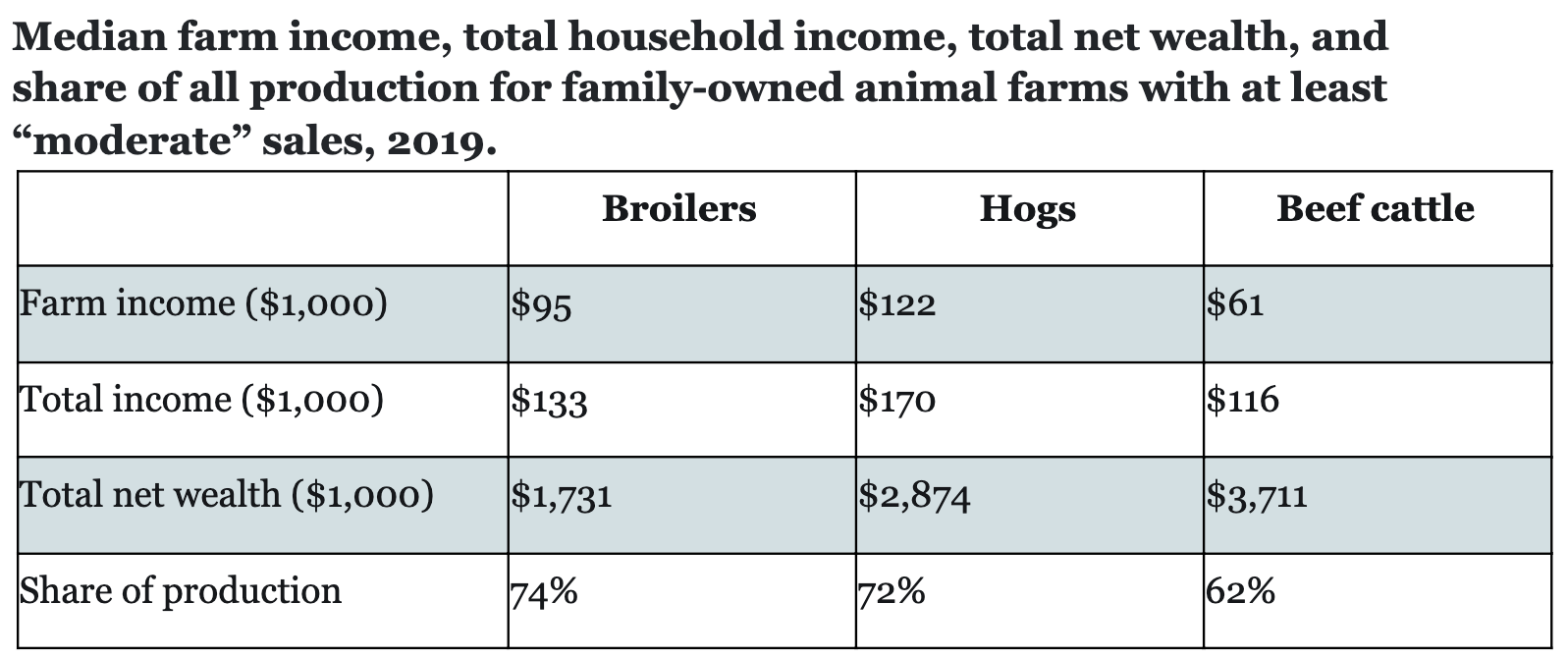

Farms that do engage in market production tend to make large amounts of money. Only about 340,000 farms—80 percent of them family-owned—accounted for 90 percent of sales in 2012. These are what USDA calls “farm businesses,” a category that excludes retirement and lifestyle farms; we also exclude family farms with less than $150,000 in sales. Even farm businesses with only “moderate sales” have a median farm income of $46,000, a median household income of $95,000, and a median net wealth of $1.8 million. “Midsize” farms make a median of $102,000 off farming and have a total net wealth of $2.4 million. These figures shoot through the roof for larger operations.

Many readers will be surprised to read that farmers have so much wealth, since antitrust journalists often point out that total farm debt is at an all-time high. They do not mention that farm assets have increased at even higher rates—in fact, assets exceed debt—nor do they adjust for inflation. Farms also often have substantial non-farm wealth they can draw on when their incomes dip. Financial success keeps farmers invested in the system: studies of campaign contributions have found that agriculture is among the most conservative industries , and a poll from last year found 80 percent of farmers approved of Donald Trump.

Animal farmers, who figure prominently in the conventional antitrust narrative, are no exception. David Dayen, in “Monopolized,” writes that “a 2013 Pew report noted that 71 percent of all chicken farmers earn incomes below the poverty line.” Zephyr Teachout uses the same figure in “Break ‘Em Up.” The source for this figure appears to be an unpublished 2001 report that found 71 percent of households whose only source of income is a chicken farm were in poverty. The comparable number for today is not readily available, but USDA data (released for this article) show that even the lowest-sales broiler farm businesses have a median household income of $69,000 and a net wealth of over $1 million. The figures are similar for cattle and hog farmers.

None of this is to say that there are not chicken farmers, dairy farmers, and some other farmers who struggle. But the data tells us that, to an overwhelming degree, farmers are wealthy. The story is quite different for farmworkers.

Farmworkers perform most of the work in American agriculture, yet they are relegated to a second-class status. A special tabulation we received from USDA shows that farmworkers work 60 percent of the hours on the farms that account for 90 percent of all agricultural production. Yet they earn only a fraction of the money. Farmers may only earn 15 cents of each food dollar, but farmworkers receive only 1.2 cents—and split those cents among more people, since there are far more farmworkers than farmers.

Data on farmworkers in animal production are patchy, but an expert who studies farm labor in California found they may earn about $30,000 per year. Crop workers, meanwhile, have a median annual income of $17,500-$20,000 and a third have family incomes below the poverty line. The average crop worker has an 8th grade education, 60 percent cannot speak English even “somewhat,” and as many as two-thirds are undocumented. They also often lack safe drinking water, work under body-destroying labor conditions, and are exposed to dangerous levels of pesticides at much higher levels than farmers. With no hope to purchase enough land to enter commercial farming, they labor, as researcher Philip Martin writes, in “an apartheid industry.”

The farm lobby and other conservative interests work hard to keep farmworkers under their control. Recently, they pushed President Trump to expand of the H-2A visa program, which some farmworker advocates compare to slavery. Large farms do their hiring through subcontractors that use the threat of deportation to keep wages down and impede unionization.

The mainstream antitrust movement is aware of these problems and will readily concede the need for greater labor protections. But their unmistakable focus is on farmers, which has led them to endorse a trickle-down theory of reform in which farmers, post trust-busting, will share the extra profits they capture with their workers. According to antitrust advocates Sandeep Vaheesan and Claire Kelloway, “Reducing the oppressive buyer power of massive retailers like Walmart, and dominant meat processors, like Tyson, would help return a larger share of the food dollar to producers, and, by extension, their workers.”

This sounds logical: if farmers had more money, they’d have more of it to share with their workers. But the data makes clear that there is little to no relationship between farm profits and farm wages. When farm profits spiked in the mid-2000s, wages stayed level. When profits hit new highs in the early 2010s, wages rose slightly, then climbed as profits fell again. Philip Martin, the scholar of farm labor, attributes the recent rise to a slowdown in immigration and state-level increases in the minimum wage, not increased generosity among hiring managers.

Research on meat processing and packing workers also cuts against the antitrust trickle-down theory. Scholars who have examined working conditions in meat processing and packing industries have found that the rapid dissolution of union power, not consolidation, is responsible for worsening pay and labor conditions. In fact, workers at large meatpacking plants enjoyed substantially higher wages than those at smaller companies prior to a collapse of unions in the 1980s and 1990s. Agricultural workers don’t need wealthier bosses, they need more rights—to unionize, to live free from harassment and mistreatment, to have decent food and housing, to collectively own the land they work.

The mainstream antitrust approach also does little to solve more fundamental problems. In 1524, the German peasant leader and preacher, Thomas Müntzer, lambasted the nobility for taking living creatures as their private property. He wrote, outraged, “that all creatures have been turned into property, the fish in the water, the birds in the air, the plants on the earth—all living things must also become free.” Karl Marx approvingly cited Müntzer 320 years later, when he argued that capitalism not only degrades how we relate to each other, but also how we relate to nature. As long as we treat living things as commodities, neither they, nor we, will be free.

A programmatic path to the liberation of all things is beyond the scope of this post— instead, we offer a critique of the antitrust narrative focused on farmers.

Antitrust enforcement can be a useful tool at times, but when its proponents use concentration to explain all the ills of agriculture, they distort reality. The break ’em up approach may distribute property rights in human and animal misery more evenly, but it does not address the exploitation at the heart of the system.

The antitrust movement has a profoundly flawed analysis of the farm economy. Its proponents argue that, in effect, tending to the needs of a small, highly conservative, and well-off constituency will redound to the benefit of their workers and society. But it is farmworkers, not farmers, who are already at the forefront of movements against environmental abuses and labor violations by their employers, that is to say, farmers. They also have the ability, through withholding and redirecting their labor, to shut down and reshape food production in the United States. Antitrust writers argue that breaking up agribusiness will help farmers and farmworkers alike. They dream of a cross-class alliance, but deny the intense conflict already with us, playing out every day in fields and farmhouses across the country.