Childcare subsidy policies increasingly promote formality as a proxy for enhancing quality and redistributes resources accordingly. As my forthcoming article argues, this formalization trend has under-acknowledged yet profoundly disastrous consequences for home-based providers, who are predominantly working-class women of color, and the disproportionately low-income working families they serve. This case study exposes the potential limitations of universal benefits to meet the particular needs of the most marginalized.

The U.S. childcare economy is internally diverse, including both formal childcare centers and various forms of home-based, often informal, care. Centers, usually larger and incorporated, tend to follow more rigid health and safety regulations, employ more formally-educated workers, and more readily incorporate standardized, expert-made protocols. Accordingly, center-based care yields higher quality scores and better educational outcomes for children, especially those above three. Home-based care, often a solo practitioner providing paid care in her own living room, tends to have lower costs, longer and more flexible hours, and more stable caregiver-child-parent bonds. Because providers often come from the same community as the child’s family, the sector tends to provide culture-compatible care and support low-income parents’ work and family life. This mode of care especially serves the needs of low-income working families from marginalized communities. Parents with nonstandard working hours, families in inner-city and rural areas, and immigrant families are more likely to rely on informal, home-based care. For all providers, their quality of care is highly responsive to the volume of resources available.

Even though government subsidies are highly restrained and contingent under a free-market family policy regime, they play a significant role in structuring the childcare economy since players operate on razor-thin margins. The Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) is the primary federal program that subsidizes the childcare through payments for care to children from low-income working families. Aside from a small “quality set-aside” for professionalizing childcare workers, CCDF pays childcare providers directly at government-stipulated rates for their service to eligible families. Providers who accept CCDF funds must comply with special regulatory requirements in addition to baseline state childcare regulations. In other words, to receive childcare subsidies, a low-income family must first satisfy the state’s income and work eligibility and then find an available childcare provider willing to participate in the subsidy program.

Started as a work promotion program in the late 1990s, CCDF initially nourished the home-based sector, which served and staffed many welfare-to-work mothers. However, since the late 2000s, state and federal policies have switched from maximizing low-income families’ access to subsidized childcare to prioritizing formality and quality of childcare. This switch was and locked in by a 2014 federal reauthorization act. Using formality as a proxy for quality, the CCDF programs today prefer more established market players who work better with state bureaucracies than those informal, family-like providers. Under this framework, CCDF subsidy programs 1) continuously reallocate resources from home-based and smaller providers to larger centers, 2) enhance regulatory requirements for subsidized providers, and 3) incorporate expert-made standardized quality measurements into subsidy calculations. The current regulatory and quality-measurement regimes were designed to promote a center-based ideal that does not recognize the benefits of home-based care. The interaction among these measures amount to a formalization trend in the subsidized childcare market that disadvantages home-based providers. Nevertheless, the quality-oriented reform so far has failed to meaningfully enhance subsidy rates—the most significant indicator of the quality of care.

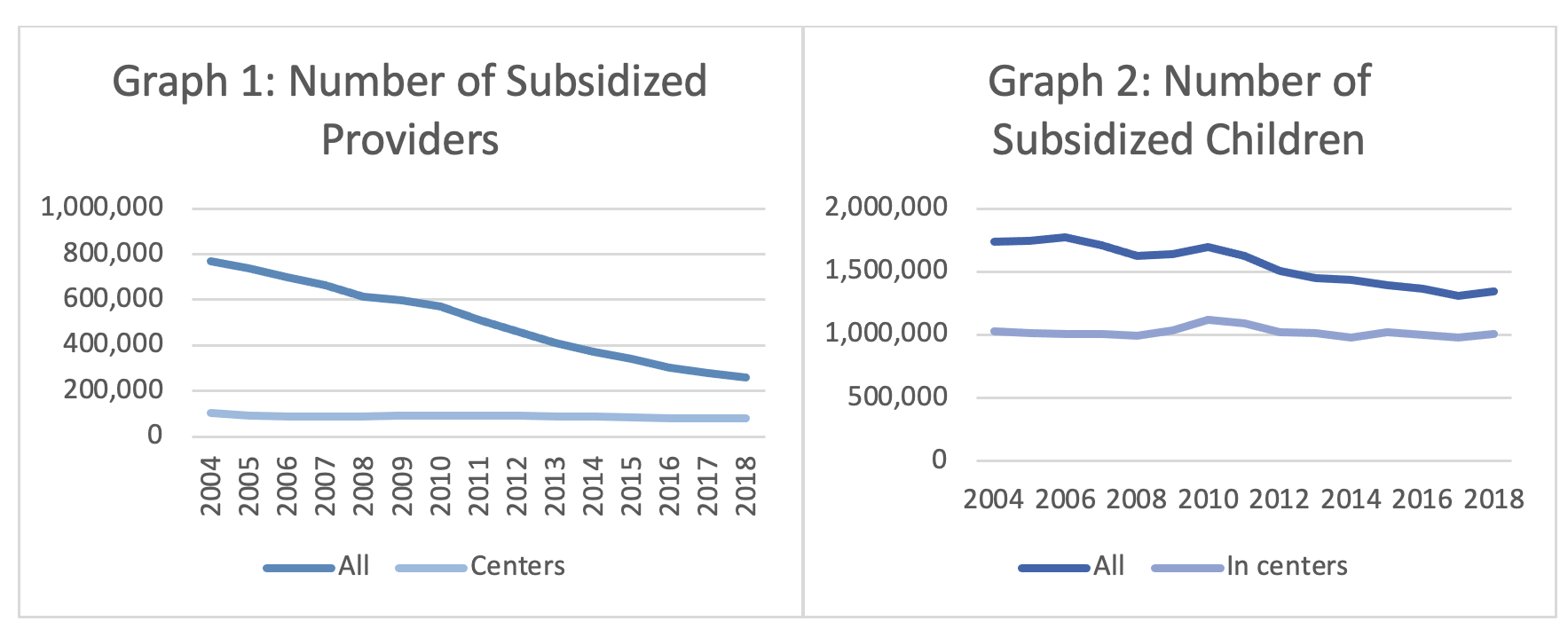

The immediate result is that the majority of small home-based providers, faced with increasing obstacles to dealing with the expanding bureaucratic requirements, have exited the subsidy system. Between 2006 and 2018, over 70% fewer home-based providers nationwide received CCDF subsidies. The exodus caused a significant decrease in the total number of subsidized providers. The number of subsidized children also dropped by 24 percent during this time. Those children continuing to receive subsidies are more likely to be placed in formal care than in the previous era.

This formalization reform redistributes material resources, value recognitions, and access to childcare across different parties in the childcare economy. Among providers, formalization benefits relatively large centers while threatening home-based providers’ survival. Centers with adequate manpower align with the quality protocols draw higher subsidy rates and other professionalization-related resources and, ultimately, perform better in both the subsidized and private markets. In contrast, falling out of the government subsidy systems, home-based providers struggle between two sub-optimal choices: demand higher payments from their clients and cut back quality or supply to save costs. Many are inevitably pushed out of business.

Channeling subsidized children to centers has adverse effects on home-based providers in the private market, too. Centers tend to draw children most compatible with their care—older children in need of shorter-hour and less labor-intensive care. This leaves home-based providers with a higher concentration of infants, toddlers, and children needing odd-hour and/or special care, increasing their operating costs per child. Given the resource constraints of low-income parents, these providers often struggle to reach a cost-balancing charge even when the demand for home-based infant and toddler care remains robust. Accumulating all these factors, the number of small home-based childcare almost halved between 2005 and 2017, dragging down the serving capacity of the entire childcare economy.

For the childcare workforce, formalization reform has weakened a source of prosperity while expediting professionalization. CCDF regulatory requirements make it more difficult for providers to operate self-owned businesses out of their own homes—a trade was often taken by older women of color—while enhancing the pay and career potentials for professional childcare workers, who are younger and better educated.

Among low-income families, formalization redistributes de facto subsidy eligibility from working poor families to impoverished families in crises, whose children are often placed with subsidized centers as part of the interventions from the Child Protection Services. Families who cannot or do not want to send children to a center (again, often due to schedule, geographic, language, and/or culture reasons) must forego subsidies, worsening their work/care struggles.

Even among families who continue to receive subsidies, switching from informal to formal care redistributes the benefits within the family. Children receive increased intellectual stimulation and socialization at centers but lose the stable bonds with their caretaker and other children and exposure to the community culture. Parents may appreciate children’s better performance at school down the line, but they face heightened immediate stress in sticking to centers’ non-negotiable hours and co-payment schedules. Also, the two modes of care strike two different parent-provider-child dynamics. Home-based providers are more likely to trust and support parents, even in episodes of parenting struggles. Center workers, by contrast, are trained to work more closely with Child Protection Service and may expose the families to more risks of state surveillance and racial and class biases in the CPS system.

To sum up, the current subsidy regime fails to support modes of care that most benefit low-income families and women, as both users and providers. Rather, CCDF promotes a market standard of quality that reflects experts’ evaluation of child well-being, which does not adequately reflect low-income parents’ needs for flexible childcare or the relational dimension of child well-being. This market model caters to the demands of professional parents’ and the offerings of professionalized childcare workers. Whereas all families with children benefit from some form of public support, families of different conditions demand different modes of childcare. A childcare subsidy regime—either in its austere, means-tested status quo or a more expansive, more universal version—must balance the competing goals of promoting broad access with meeting the diverse needs of different groups.

However, formalization reform’s devastating outcomes on home-based providers and low-income parents are by no means unavoidable. Nor is community-oriented, home-based childcare incompatible with quality enhancement. Grassroots labor organizations have proven the potential of a bottom-up alternative to increase childcare quality in the home-based sector through community labor organizing. Instead of channeling low-income children (and childcare workers) into centers, the grassroots organizing model channels training, technical assistance, and relationship-based support to home-based providers, enhancing their performance in educational quality without sacrificing the relational texture of their care process. The organizing process also reaches the marginalized providers and builds a peer-consulting collective among them, reducing the isolation associated with home-based work. Through these community-based providers, the resources also flow to the low-income families they serve. The grassroots organizing approach demands a more nurturing state regulatory regime responsive to the characteristics of home-based care and continuous support from government subsidies. In addition to strengthening the home-based sector, the state could also use subsidy policies to enhance schedule and payment flexibility, stabilize relational bonds, and introduce more community-embedded care in centers, building a childcare economy more responsive to low-income families’ needs. More profoundly, similar to healthcare, the “quality” of childcare can never be isolated from the overarching political agenda to empower and strengthen marginalized communities.