This post is part of a symposium on Ezra Rosser’s A Nation Within: Navajo Land and Economic Development. Read the rest of the posts here.

***

In the sci-fi short, The Sixth World, filmmaker Nanobah Becker poses the unthinkable: Diné people on a space mission to colonize Mars. During the flight, the crew encounters a crisis. The cabin becomes oxygen-depleted due to a failure of genetically-modified corn engineered to fuel the spaceship. Fortunately, astronaut Tazbah Redhouse (Jeneda Benally), who reconnects with the teachings of her elders during an in-flight dream, is able to save the mission by drawing upon a hidden stash of Diné heritage corn.

The mission, called “Project Emergence,” invokes Diné stories of their emergence from the lower/prior worlds into the present, establishing a temporal and narrative arc from time immemorial to the future. Yet, in Becker’s telling, colonizing Mars is not a linear journey into a post-apocalyptic future, as we might expect from the genre of sci-fi, but is instead part of a genre of indigenous futurism and “decolonizing encounters.” Using recursive images of Monument Valley – once lined with cornfields, then lined with spaceships – Becker’s Project Emergence is in fact, a return to homeland: it is less a colonial mission and more a manifestation of the future (a “Sixth World,” following Diné metaphysics) within the present and the past. The journey taken by Redhouse and her colleagues confirms Diné epistemologies and foundational laws not as relics of a disappearing past, but as critical lifeboats where “rescue” from anthropocenic damage hinges upon the affirmation of Diné self-determination, in landscapes shaped not only by climate change, but also by colonialism, capitalism, and industrialization.

Ezra Rosser’s A Nation Within follows a different temporality. Moving from “past to present to future,” Rosser offers a rich socio-historical, legal chronology of a Nation that emerges in relation to perhaps the most central, kindred actor for Diné futurism: the land itself. As Rosser writes, “Land provides the basis for the independent sovereignty of the Navajo Nation and creates the space necessary for Diné families to live distinct lifeways.” This is perhaps why the departure of the Project Emergence mission, in Becker’s film, is so affectively jarring, as she forces us to contemplate a nearly unthinkable speculation: what would it mean for Diné people to collectively leave their homelands between the four sacred mountains?

Becker’s cinematic response is much like Rosser’s textual reply: it would be the end of the known body politic; and as such, the only place to go is back home. It is not Mars, but Monument Valley, after all. To remain in place – against the violence of livestock reduction, uranium extraction, an intractable coal economy, a federal “freeze” on development, and today, the intensifying drought and water rights battles that are strangling the Colorado River, as Rosser describes – is a political act.

Most admirable in Rosser’s book is the commitment to a diversity of perspectives, along with his commitment to writing against the “Noble Savage” tropes in environmentalism that flatten the sovereignty and humanitiy of Diné people. As Rosser is right to point out: Diné land is sacred because it is the actual land of emergence; it is a material, not mystical connection. In Landscapes of Power: Politics of Energy in the Navajo Nation, I wrote against similar settler tropes, drawing on what Lila Abu-Lughod calls “ethnographies of the particular” to pry open stale and damaging stereotypes with stories of how people live and embody contradictions, open-ended possibilities, and complex dimensions of being human. Rosser’s commitment to what we might call “lived experience” makes a significant contribution to legal scholarship, in particular, which all too often operates from a birds-eye view of policy and federal Indian law, rather than, as Valerie Lambert reminds us, the need for “on-the-ground experiences” of Indigenous lifeways.

For two decades, I have thought alongside Diné environmental justice activists and scholars (in geography, anthropology, American Studies, and history) to try to make sense of the unique positionality of something we might call “Diné environmentalism.” Rosser takes on a force that I also have written about, what he calls the “environmental paternalism” of outside groups that fail to fully understand the complex dynamics of history, legality, and self-determination for Diné people and, therefore, miss what is really at stake in environmental defense and sovereignty. As I think about in Landscapes, Rosser elaborates: that homeland is sacred does not intrinsically mean that tribal lands should not be used by the people, for different ends. The locus of anti-colonial analysis thus does not always fall in hegemonic versions of environmental protection; and what it looks like to get at justice holds, always, nationhood at the center.

In other words, equitable and just responses to ecological degradation do not always align with conservation and preservation initiatives that view “nature” as devoid of human history and indigenous sovereignty. My research in the Navajo Nation and in Austronesian/Indigenous Taiwan confirms that the concept of terra nullius is alive and well in federal environmental regulatory processes of settler states (from US failures to incorporate Indigenous worldviews to hunting restrictions on Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan). The current planetary crisis is, at the same time, a crisis of recognition of the political difference of polities that predate settler states. Environmental justice that centers nationhood and tribal sovereignty makes the terra legible as homelandscapes, even as ecological ruin and loss might appear to define those places; pursuing ‘energy justice’ as an exertion of nationhood within and against the settler state in this sense, as the Navajo Nation has done from at least former Chairman Peter MacDonald onward, does not guarantee a specific, “green” technology so much as it engenders a political theory of “collective continuance” as rightful response to planetary crisis.

We are left with a lingering question, however, regarding the title of Rosser’s book: A Nation Within references, without stating, a higher-order sovereign. Within what, exactly? Audra Simpson argues that Native Nations exist within a “nested sovereignty” of the settler state; Jean Dennison argues that such nesting within the jurisdiction of a county (such as Osage County, Oklahoma) might be challenged and overcome, with an alternative, more inclusive accounting of citizenship based in territory rather than blood; Kevin Bruyneel offers the idea of tribal sovereignty as a “third space,” neither inside nor outside settler polities. There are, indeed, ways to think against the grain of “the within,” and this is where I look forward to further dialogue not only with Rosser on this precise question, but with Diné philosophers and political theorists, as well as artists and filmmakers, like Nanobah Becker, who are imagining alternative (and gendered) geopolitics of self-determination, where emergence is primary and foundational, pre-figuring the settler state, rather than “within,” which assumes a pre-existing (settler) sovereign. To move from the within to emergence is not a fantasy trip to Mars, but a return home to re-establish self-determination in material, historical terms.

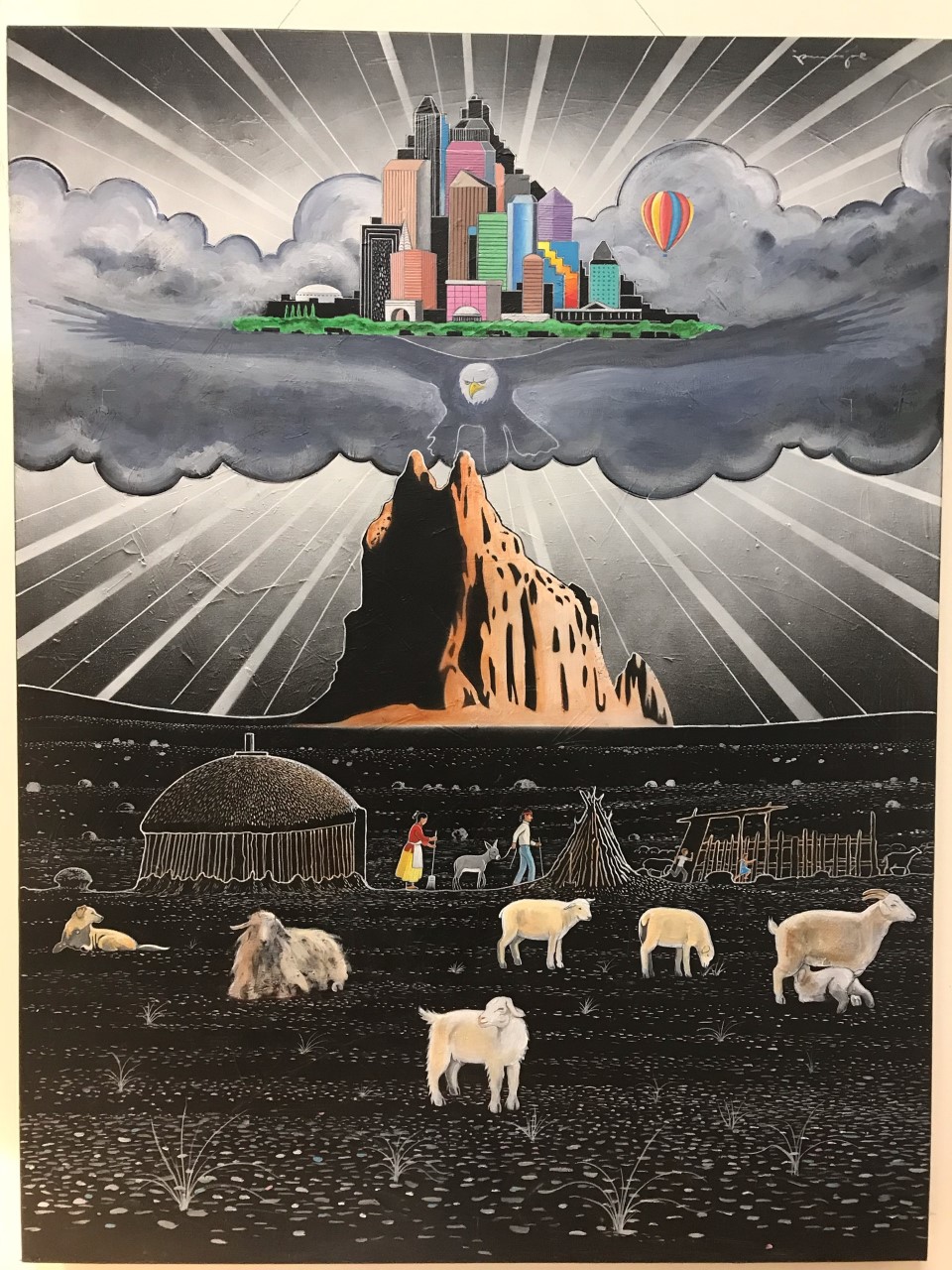

Cover art by Jared Yazzie of OXDX Clothing.