Just days after President Trump signed the Republicans’ budget reconciliation bill into law, Equifax’s CEO Mark Begor celebrated its passage on the company’s earnings call. The windfall he expected from the law was “just massive,” but he was not celebrating the bill’s lavish corporate tax breaks. He was applauding new rules that will make it harder for millions of eligible Americans to receive their healthcare and food benefits – and eager for the opportunity to profit from them:

…increasing the frequency of CMS redeterminations from annually to semiannually, adding community engagement or work requirements for certain Medicaid recipients, and in SNAP, tying federal funding to error rates and enforcing work requirements. These changes are all positives for our EWS (Equifax Workforce Solution) core government business.

The CBO conservatively estimates that these rules will strip Medicaid coverage from over 7 million people. For millions of working Americans this maze of new rules will mean losing their life-saving health insurance and financial ruin. For Mark Begor, Equifax, and other government contractors, this maze of new rules means profit.

“Only Equifax”

Today, Equifax extracts over $800 million worth of contracts from the federal government and state governments each year. Much of that total is for access to its Workforce Solutions product, the Work Number, which provides data on workers’ income and employment. The Work Number’s basic business model is to purchase exclusive rights to worker data from employers and payroll providers (often without a worker’s knowledge) and then sell that data to banks, creditors, and governments for a profit.

Since the United States, unlike many of our peer nations, has opted to means-test core government programs like healthcare, the government has become a huge buyer of this income data. In order to prove that a person is eligible for Medicaid, an Affordable Care Act Marketplace subsidy, or any number of safety net programs, state governments and federal agencies pay Equifax for data to verify that person’s income.

Siloed federal and state agencies will often pay Equifax half a dozen times for the same piece of income data about the same individual. For example, if a recently laid off worker applies for Medicaid, SNAP, and home heating assistance (HEAP) at the same time, a state’s Medicaid agency, human services agency and a local social services department may each pay Equifax (often a different price) for the same worker’s income data.

Unsurprisingly, Equifax has worked to establish market dominance for this spectacularly lucrative business. Through aggressive acquisition of competitors and exclusive deals with payroll companies, Equifax has hoovered up the rights to data for 99 million American workers. Having arguably monopolized electronic verification of income, Mark Begor bragged earlier this year “we don’t feel an impact from the one or two participants that have much smaller businesses.” This feeling of dominance is nicely captured by the company’s marketing slogan “Only Equifax”.

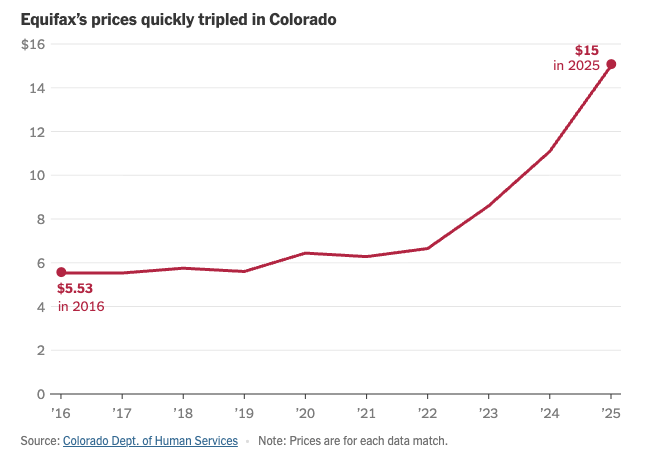

With governments entirely reliant on Equifax to administer life-saving benefits to millions of low-income Americans, steep price hikes quickly followed. The New York Times uncovered that in many places, the toll paid to Equifax for the Work Number doubled, then tripled, and more than quadrupled in only a few years. Local, state, and federal agencies have helplessly watched their public funds raided, boxed in by the dual forces of means-testing requirements and unconstrained market power.

The President’s bill, which passed in July 2025, supercharges this dynamic. The law doubled the number of times state Medicaid agencies need to verify many individuals’ income each year, meaning doubling the number of tolls paid to Equifax. The law adds new requirements that a worker must verify at least 80 hours of work each month – employment data held almost exclusively by Equifax. If you had tried to find the most efficient way to transfer taxpayer dollars from healthcare to a databroker, you could not have done much better. And Equifax is sure to put those public dollars to good use, like by funding $3 billion in stock buy backs.

Complexity as a Business Model

Verifying a workers’ income for government health insurance, and Equifax’s capture of that function, is just one illustrative component of the Rube Goldberg machine that comprises America’s rigorously means-tested safety net and its vulnerability to corporate capture. Complex eligibility rules and administrative hurdles to determine who deserves coverage and who does not are fractured across government agencies and jurisdictions. Many research studies, magazine spreads, and books have documented how this complexity keeps millions of eligible people from accessing billions of dollars in benefits they are entitled to – the unemployed are locked out of their unemployment insurance, the uninsured are never enrolled in their health coverage, and the hungry are denied food assistance.

Vice President Harris’ announcement of “a student loan debt forgiveness program for Pell Grant recipients who start a business that operates for three years in disadvantaged communities” is perhaps the best recent caricature of how increasingly complex eligibility rules have failed to deliver for millions of Americans. And this labyrinth of eligibility rules doesn’t just fail the intended beneficiaries – the administrative complexity they create presents an enormous opportunity for profit by government contractors.

After the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency was ended by Congress in 2023, I led a government team at the United States Digital Service to help fix state Medicaid systems that had fallen into crisis. As we rushed to put out fires in Red and Blue states alike we encountered the same problem – entrenched government contractors like Deloitte had charged millions to build error–prone systems that state governments had no capacity to fix. Billing by the hour, growing the complexity and incomprehensibility of these systems proved profitable. Changes that my team could make in minutes were quoted as requiring hundreds of billable hours. When we discovered that nearly 500,000 children had lost their health coverage improperly because of software errors, many system contractors were painfully slow to reinstate coverage for those children and fix the errors.

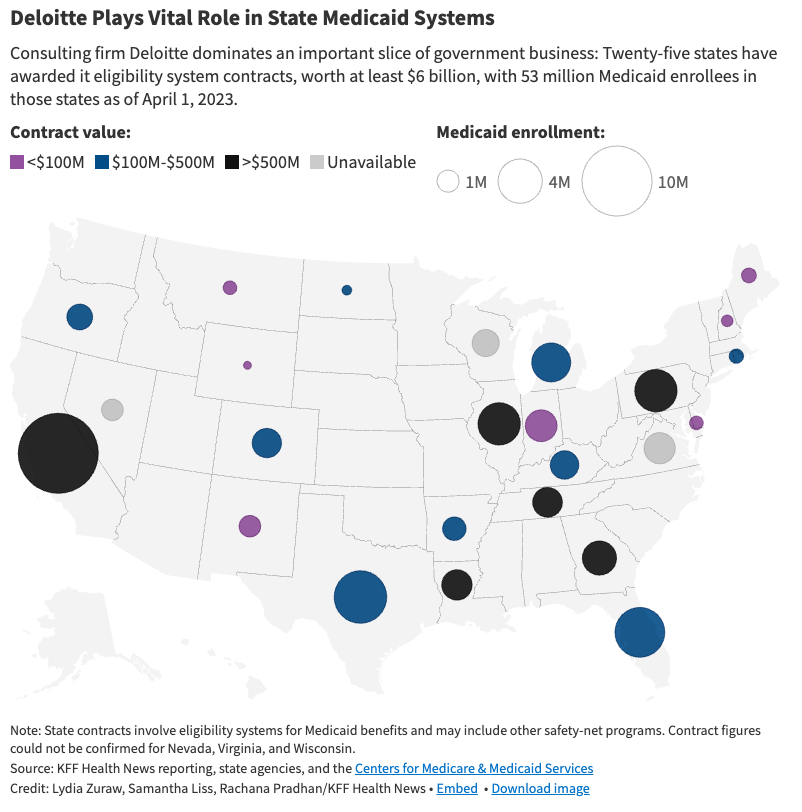

Just as Equifax pursued domination of income verification, Deloitte has done the same for this Medicaid eligibility software. A KFF investigation found that:

Twenty-five states have awarded Deloitte contracts for eligibility systems, giving the company a stronghold in a lucrative segment of the government benefits business. The agreements, in which the company commits to design, develop, implement, or operate state-owned systems, are worth at least $6 billion.

The federal government foots up to 90 percent of the bill for these contracts, spending as much as $10 billion each year – more than the National Park Service, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and U.S. Secret Service annual budgets combined.

Again, new work requirements for Medicaid highlight the profits to be made from adding complexity to the safety net. Since Georgia implemented work requirements in 2020, they have spent twice as much on Deloitte consultants and administrative costs as on healthcare for people. As the other 55 states and territories are now forced to join Georgia and implement new work requirements, millions will lose their healthcare and Deloitte will cash in.

Enforce, build, and simplify

Equifax and Deloitte’s capture of the complexity of America’s safety net is egregious, but far from unique. Yet a more rational system is possible, one that does not sacrifice public dollars to private data brokers and poorly performing contractors. As urged by Luke Herrine, it’s time to begin planning and building the alternative path in the weeds.

The first step is to better coordinate the government’s significant buying power and enforcement tools to break monopolies that prey on the public sector. The minimum the federal government can do is back-up state and local governments when negotiating with powerful companies. There is no reason Kansas’s Department of Children and Families should be paying Equifax $19.39 to access the same data about the same person that CMS pays $5 for. The same goes for Medicaid eligibility software where state governments are the only buyers and the federal government is paying the vast majority of the cost. The federal government should use its existing authorities to negotiate, publish, and enforce lower enterprise-wide prices that all agencies and states can benefit from. Further, the anti-competitive behaviors displayed by these companies – especially those that harm the government itself – are ripe for antitrust scrutiny at the state and federal level.

The second is to build public infrastructure to operate public programs instead of outsourcing core state functions to entrenched and poorly performing contractors. In both the case of Equifax and Deloitte’s domination of the safety net, building public options is urgently needed and fortunately within reach. Each of these public options can be designed to remove administrative burdens on people, preempt the kinds of government data abuses we’ve seen perpetrated by DOGE, and align with the core principles of K. Sabeel Rahman’s anti-domination framework.

Today, states can build public income verification services in-house by modifying and using income data that they already collect, instead of relying on a faulty private data broker. This public option could be designed with a privacy-first architecture that minimizes the data stored and shared to foreclose potential punitive uses. CMS can build an open source version of Medicaid eligibility software and allow states to use it and build on top of it for free, instead of endlessly paying the same bad contractors full price in every state and territory. This open source software would empower state policymakers with more visibility into the administration of their programs, allow improvements to be shared freely and quickly across states, and help dislodge entrenched contractors. Following the successful model of IRS Direct File, building these two public options will require an investment to develop in-house government capacity, but will save taxpayers billions and dramatically improve the delivery of services.

The third step is to simplify eligibility criteria for public programs in the first place, curbing the neoliberal obsession with complex and federated means-testing that creates the opportunity for corporate capture. The administrative benefits and political durability of simplifying eligibility criteria are well documented. The recent example of universal free school meals is one model of success – eliminating administrative burden on people, minimizing contractor involvement, and maximizing benefits delivered. It’s no accident that Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s popular policy proposals – fast and free buses, free childcare, and freezing the rent – are simple and universal. In the federal context, moving to a single payer healthcare program like Medicare for All would render much of the broken, expensive, and captured means-testing machinery that I worked to fix after the pandemic unnecessary. In part due to the relative simplicity of eligibility and benefits, Medicare’s administrative costs (1-2%) are about half of Medicaid’s (3-4%) and an order of magnitude less than private insurance (15-30%). Simplification offers much less room for capture by for-profit government contractors.

We are currently heading further into crisis on each of these fronts; the federal government is abandoning enforcement efforts against dominant contractors, shutting down and privatizing successful public options, and adding complex eligibility rules for contractors to profit from. We must advance the opposite agenda at both the state and federal level by holding anti-competitive contractors accountable, building public options in-house, and simplifying eligibility rules to better serve people, not corporate profits.