“Political economy” has an antique ring. More than a century ago, the field of “political economy” began to give way to what was called “economics.” By the mid-twentieth century, political economy was forgotten; economics ruled the roost. But what is old is new again. Political economy is coming back. Economics sidelines the distribution of wealth and power; political economy puts it at the center. Economics claims to be value-free; political economy asks: “What is the good economy?”

Because it blends the normative with the analytical and the economic with the political, political economy always has lent itself to constitutional discussion. And when you go back to the eighteenth , nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, you find that judges, lawmakers, reformers, advocates, constitution-makers and policy-makers of all stripes looked at and argued about the Constitution through a political economy lens and the political economy through a constitutional lens.

They started from the premise that the Constitution was inevitably entwined with – and not neutral with respect to – the economic order. Thus, many matters that we see as policy debates about the maintenance or reform of institutions affecting the distribution of wealth and economic power they saw as the stuff of constitutional law and politics.

We remember well one such perspective: late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Lochnerism. But Lochnerism had a largely forgotten interlocutor and rival that Joey Fishkin and I have called the anti-oligarchy Constitution and the democracy of opportunity tradition. Springing from some of the same ideological seedbeds, this rival tradition held that the constitutional order requires a political economy in which wealth and social and economic power are widely dispersed, not concentrated – one with restraints against oligarchy, and one where everyone has real access to decent livelihoods, material security and a degree of voice and authority in economic as well as political life.

Drawing on these precepts, generations of reformers contended that the Constitution required a variety of structural reforms: anti-monopoly measures; overhaul of the banking system to disperse capital and credit; a mass Democratic party to aggregate the power of the laboring many against the monied few; mass industrial unions and a broad right to strike and boycott to boost the economic and political clout of the industrial working class; an end to corporate campaign contributions to rein in corporations’ constant conversion of economic power into political domination.

After the New Deal, this tradition of constitutional political economy was largely forgotten. Partly, that was a result of old-fashioned repression. In the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, a narrow anti-communist/Cold War “consensus politics” eclipsed the confident liberalism of New Deal America, and those who stuck with robust, left-leaning views about constitutional political economy were purged from mainstream politics.

Partly, too, the New Deal did bring a great access of power to organized labor and unprecedented material security for a broad swath of white male industrial workers, who became a new mass “middle class.” In the narrowed political mainstream, it was thought that the nation’s class problems had been largely solved. The constitutional-equality work that remained was bringing women and racial minorities into the fold of first-class citizenship.

The Constitution, according to this Cold War brand of legal liberalism, is about civil rights and liberties and racial and gender justice; it has nothing to say about “economic rights” nor about distributional issues along class lines. No surprise: During the same decades as this post-New-Deal liberalism was under construction, “economics” eclipsed “political economy.”

Constitutional political economy did not die out entirely, of course. The right wing of the Republican Party and the libertarian side of the academy kept right on talking about it. They published journals about it. They launched the “Right to Work” movement, and they enacted laws to resurrect liberty of contract.

Meanwhile, liberals and progressives continued to champion redistribution – and never more boldly than today. We want to rekindle campaign finance regulation; we want an overhaul of banking and credit; and we want to revive antitrust and broad social insurance. For the first time in more than half a century, Democrats in Congress and in the presidential primaries are championing fundamental labor law reform.

But as far as the Constitution is concerned, when the right says “The Constitution forbids these measures! They violate fundamental principles. States’ rights! Individual liberty!”: the left says “The Constitution does not forbid these measures! It allows them! They are good policy! And don’t talk about economic liberty as a constitutional principle. The New Deal buried that kind of argument.”

I don’t think this is the best response for the left to make. And, in a moment, I’ll get back to why. But first, speaking as a historian, I can tell you this about the New Dealers, and before them the Progressives and the Populists, and before them, the Reconstruction Republicans: they did not say to their rivals what we say to ours. They did not say, “You are wrong. The Constitution allows the redistributive measures we are championing.” Rather, they said the Constitution requires these measures.

Thus, Reconstruction Republicans said the Constitution not only permits but requires us to bar slavery from the Western territories and reserve them for black and white homesteaders; Populists said the Constitution not only allows but requires antitrust. And New Dealers said the Constitution requires a broad right to strike and organize and bargain collectively.

What did they mean? They were using “requires” in a double sense. They were making interpretive arguments saying constitutional text and principle requires these things. And they were making structural political-economic arguments, saying our republican form of government and our guarantees of equal citizenship are dependent upon a broad distribution of material freedom – a broad middle class or, later on, a socially independent working class with a collective voice in industry and politics. You could not run a republic with a citizenry of wage slaves and overlords.

For them, these two kinds of arguments – interpretive and structural political-economic – were deeply entwined. Today, we no longer say the Constitution “requires” reforms in this structural sense. We say that the structural political-economic arguments are policy arguments. Or, among constitutional theorists, we may say they are “small c” but not “capital C” constitutional arguments – a distinction that the historical tradition I’ve been sketching would not have drawn, or, at the very least, would have insisted was far more of a continuum than a binary.

I’ve flagged some of the reasons for this sea change. Another is the rise of judicial supremacy. More often than not, throughout the nineteenth century, lawmakers on all sides of political-economic debates believed that they were the nation’s primary interpretive actors or “expositors” of the Constitution, as well as its primary policy makers. In this universe, “the Constitution” was a text and tradition one interpreted; but it was also a system of government, whose powers and purposes one implemented and pursued over time, through political and legislative action. And so, lawmakers devoted countless hours arguing about Congress’s affirmative duties under the Constitution. In our judicialized constitutional culture and imaginations, these old arguments about government’s duties under the Constitution barely make sense.

But remember, progressives only came to love judicial supremacy during the Warren Court era. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, all these generations of reformers were fighting judicial supremacy. And in those decades-long battles with the courts’ constitutional condemnations, they drew on the idea that it was Congress’s constitutional duty to make laws and state institutions that constructed and maintained the political economy over time, according to the precepts

- that the Constitution required government to prevent oligarchy and economic overlords, and

- it required government to repair and maintain the conditions of possibility for a broad middle class or, in later iterations, an empowered working class.

On this account, the courts’ duty was to defer the political branches’ work and help to implement it. In a few contexts, the courts did just that. But in many, the courts were opposed and fought the lawmakers’ work. Hence the decades-long clash over judicial supremacy.

And so we come to today, and why progressives should revisit this tradition of left-leaning constitutional political economy. Why not just demand economic reform? Why say the Constitution requires that government remake labor law, rekindle anti-trust, and institute co-determination and some dramatic overhaul of banking? What’s wrong with: the Constitution simply allows lawmakers to do so?

One reason is simplicity itself. Getting large structural reforms enacted will require more than electing Democrats. It will require a massive boost in working people’s political clout to counter the power of corporate wealth in the halls of Congress, no matter whether Democrats are in charge. And that boost may well hinge on rebuilding a mass movement and mass organizations of working people, different in structure and composition but comparable in clout to the industrial unions of the 1930s-60s. Getting that done will require big strikes, such as we are just beginning to see on the horizon. And most often, such strikes are illegal.

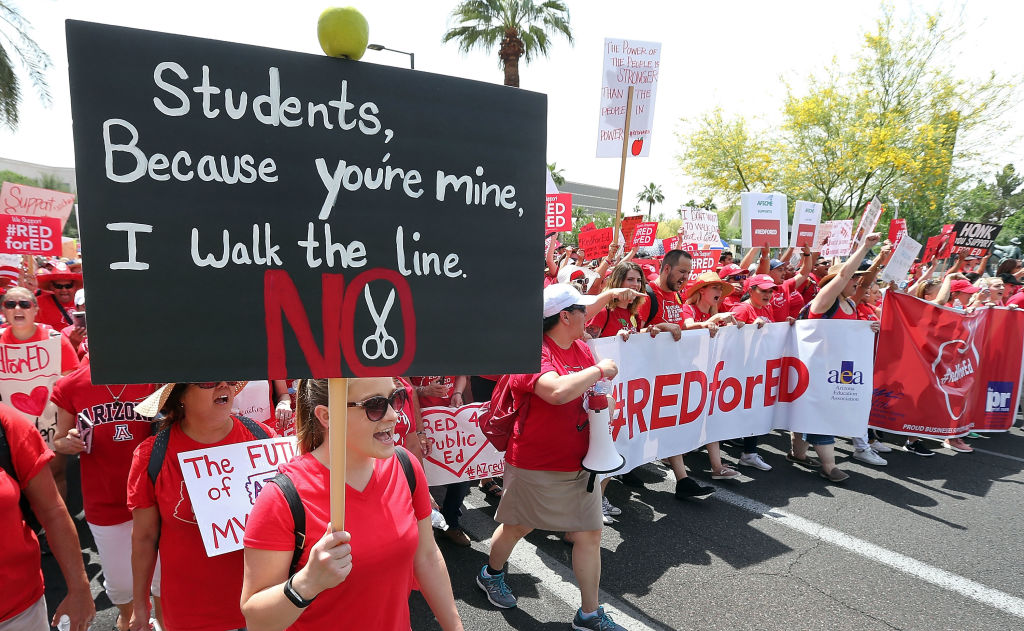

Repealing the national ban on secondary actions, for example, will require mass defiance of the ban. The same goes for repealing or neutralizing the state bans on strikes by government employees. When it comes to mass lawbreaking and civil disobedience, there is nothing like a claim on our higher law. The labor movement has a rich history of mass disobedience of anti-strike and anti-boycott decrees, brimming with constitutional claim-making against “government by injunction” and the doctrines it rested on. Kate Andrias’s piece in this series of blog posts describes how the recent state-wide teachers strike in West Virginia saw strike leaders and activists drawing on that legacy.

But there are other, broader-gauged reasons for reviving a left-leaning constitutional political economy. Imagine sometime in the next decade or so, a progressive Democrat in the White House and a Democratic Congress progressive enough to enact the kind of reforms that candidates like Warren and Sanders are mooting today. Imagine how those reforms would fare in the Roberts Court. The Court already is far enough along in fashioning a new neoliberal brand of Lochnerism that it is easy to imagine the various constitutional grounds on which the Court might strike down or gut many of these reforms.

There would arise a clash over judicial supremacy, once more. If they were going to push back hard against the Court with whatever kinds of Court-curbing measures they might fancy, progressives would need more than well-wrought bills in the pipeline. They would need to mobilize popular support. They would need to respond substantively to the libertarian, anti-redistributive constitutional discourse flowing out of the Court and the Republican Party. They would need substantive constitutional arguments on the side of redistribution.

True, they could say redistribution is simply just and fair. But if you are going to champion Court-packing, jurisdiction-stripping or other hardball measures to push aside the Court’s roadblocks to reform, you may be on far stronger ground if you can explain why the very redistributive reforms that the Court is nullifying are ones that the Constitution demands. Likewise, you may be on stronger ground if the dissenting voices on the Court are resting their dissents on just such arguments: that the Constitution doesn’t only allow, but requires the distributional measures that a reactionary majority on the Court condemns. Invoking dissenting justices’ views of the constitutional order was a key weapon in past struggles against judicial supremacy. So, it may be in the near future; and it would be good if the dissenting voices on the Court had loud and clear substantive arguments at hand.

These are constitutional arguments addressed to the specific task of facing down a neo-Lochnerian Court. More broadly, isn’t it both smarter and truer for progressives to say, attacking gross economic inequality is not only about distributive fairness but also about political freedom and democracy. Because it is about the political stakes of economic inequality, the tradition of constitutional political economy I’ve sketched makes that point sharply. The progressive turn to a judicialized Constitution helped drain away the kind of progressive constitutionalism that puts economic power – and its inextricable links to political power – front and center.

This older tradition treated the collective agency and broad participation of ordinary people in shaping and governing our political economy as a constitutional necessity. It did not hold that the Constitution dictated the specifics of basic structural political-economic reforms. There was much to debate in the policy-making arena. But the debate was inflected through and through with constitutional argument.

So, as you read the other posts in this series, consider this. Political economy is making a comeback on the left. Why not constitutional political economy? Perhaps it is time to begin to reknit what we have grown used to calling policy versus constitutional arguments, or “small-c” versus “capital-C” constitutionalism. Perhaps, we should begin framing our arguments for structural reforms like the ones these posts put forward, partly with the outlook that the future of our constitutional democracy depends on such measures. After all, don’t we believe that it does?