Like everybody else, we’re trying to process what happened in the US election last Tuesday and where it leaves us. Sorting it all out will take time, and you can expect some thinking-out-loud in these pages over the next few months. In the meantime, here is what we’re reading to try to make sense of it all.

First, voters clearly didn’t like their options, and Kamala’s closing argument — campaigning with Cheneys and urging people to save a democracy that many already feel has died — fell flat. There is a lot to excavate about the failures of the Harris campaign, the Biden Presidency, and the Democratic Party itself. Gabe Winant’s recent post-mortem is one place to start.

What to make of the new “multi-racial working-class dealignment”? Two things on our list here: the Dig’s interview with Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and Daniel Martinez HoSang’s pre-election article, which urges us to “take seriously the many reasons why minoritized people and groups are increasingly drawn to right-wing projects aimed at them.”

Though early exit polls and surveys should be taken with a grain of salt, a few things seem already clear. Trump drew enormous support from people earning under $100,000 a year and dissatisfied with the economy. According to this NBC News exit poll (and others seem to concur), around half of Trump voters cited “the economy” as the most important issue to them (compared to around 10% of Harris voters). Forty-five percent of voters thought they were financially worse off than they were four years ago — the highest number since the 2008 financial crisis. And it’s notable that voters in many red states passed measures, including paid sick leave and increases in the minimum wage, while also voting for Trump. Those folks, we can assume, are in for a lot of disappointment.

What should we make of the broad dissatisfaction with the economy? Is Dean Baker right to blame the media? Jake Grumbach offers one note of caution: “attitudes about race and immigration best separate Trump vs HRC, Biden, & Harris voters, including voters of color. Economic attitudes & real wage changes don’t.” Others, such as Adam Tooze, Claudia Sahm, and Nathan Tankus, have suggested that the explanation is instead that many salient prices — such as food and fuel — have continued to rise and/or remain high. Housing costs too have continued to be prohibitive for many, even if they have not continued to increase at the same pace (see also Tara Raghuveer). All of these authors — as well as Bernie Sanders — suggest that we need a party that can put forth an economic agenda that can speak to the profound sense of insecurity and risk that is driving so many to rage with the powers that be today.

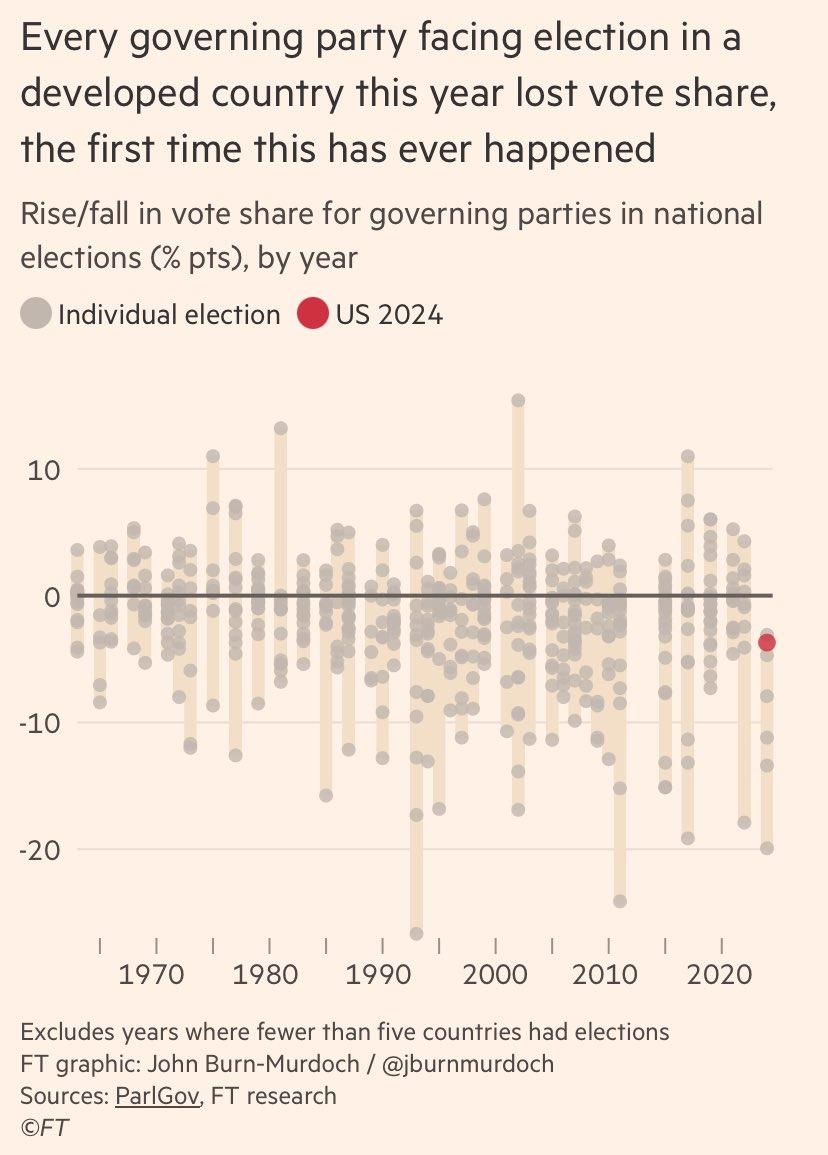

Indeed, while perhaps the dominant narrative to take hold this past week is that the election was a referendum on inflation and high prices – the FT produced this useful chart showing that every governing party in developed countries lost vote share this year – this should not be conflated with a repudiation of the Biden Administration’s aggressive fiscal response to COVID-19.

No country did as much stimulus as the United States, and, as Bharat Ramamurti pointed out, the Democrats did relatively well compared to other countries. “Rather than dismissing the entire approach because it coincided with a global inflation surge that wiped away incumbent parties everywhere,” he argues, the Democrats must “start prioritizing speed and tangibility in our agenda.” After all, the housing, care, and child tax credit elements of Build Back Better that centrist democrats betrayed would have provided concrete cost-of-living benefits to run on.

Kate Aronoff goes farther, arguing that the focus on expanding manufacturing jobs while failing to expand the care economy amounted to a failure of Bidenomics. Jimmy Williams, after his conversations with union members, observed that while union support for Harris was higher than it was for Biden, the failure of Democrats to tell a story about how they are going to make conditions better made it hard to convince many union members to vote for them. (Also check out this older piece by one of us — Amy — and Jacob Hacker, highlighting the transitory and modest impact of much of what Biden was able to provide.)

Relatedly, JW Mason (among others) has pointed out that the Democrats allowed many COVID-era income supports to expire in 2022, leaving millions of households worse off, increasing food insecurity, and increasing inequality. A substantial portion of these supports were initially adopted during the first Trump Administration (largely due to Democrats in Congress, to be clear), so for many Americans, the experience was one of Biden-era policy changes making them worse off. One of us (Luke) has pointed out that something similar is true about student debt: payments were paused under Trump and restarted under Biden. The promised cancellation never arrived – most people didn’t follow closely enough to know, nor did Biden do much to convey, that this was the Supreme Court’s fault – and the cancellation that was delivered was not nearly as widespread.

And so – what does the future hold? We’ll be exploring some of the possibilities in coming months, and we encourage you to send us your ideas. We especially want pitches that help us think about how lawyers and organizers can better exploit the contradictions in Trumpism and build toward a more effective and more progressive alternative than the current Democratic party.