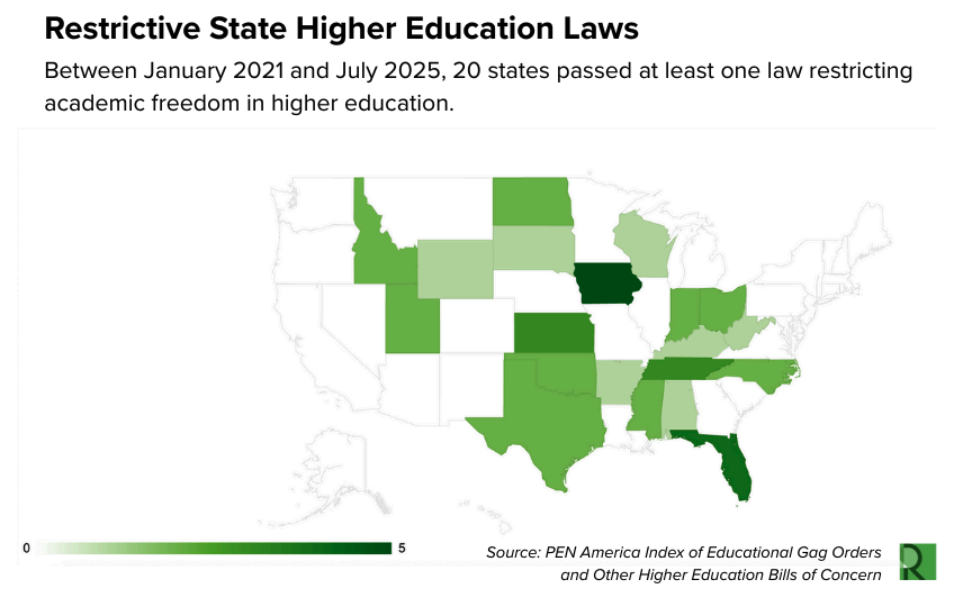

In recent years, higher education has been besieged by authoritarian political movements at both the federal and state level. The second Trump Administration’s efforts are surely familiar. It has been cutting research funding willy-nilly, screening grants with improvised algorithmically mediated ideological filters, and leveraging Title VI to fleece major universities of hundreds of millions of dollars and force them to submit to ongoing ideological supervision. For several years now, Republican-controlled state governments have been running their own experiments with ideological control: prohibiting diversity programs and the teaching of “divisive concepts,” weakening tenure, mandating “classical” education, and replacing administrators who resist. A bipartisan crackdown on students and faculty who speak too critically and openly about Israel’s crimes has been encouraged by state and federal elected officials, as well as by private university boards and militant Zionist organizations.

Both federal and state officials are taking guidance from conservative think tanks and movement organizations, which are flush with funds to oppose “wokeness” on campus, largely because right-wing donors were terrified of the Black Lives Matter movement and blamed university indoctrination. These conservative organizations have also been working to displace established accrediting agencies, remake university boards, and support on-campus militants to put pressure on faculty and administrators.

These are not, of course, the first conservative attacks on systems of higher education as independent spaces of inquiry and critical thought. But they are certainly the boldest, most sustained, and most successful attack since the McCarthy era. And, in many ways, they go beyond longstanding anti-communist and anti-leftist goals by aiming to dictate the content of the curriculum, in addition to screening out wrongthinking faculty or repressing protest.

In important respects, these attacks represent a departure from the neoliberal coalition’s celebration of institutional independence from the state, of the role of education in profitability, and of research’s role in profitable innovations. Whatever neoliberals may have thought about the ideology of faculty or the value of the humanities, they exalted the importance of “human capital” to total factor productivity and opposed ideologically driven state interference in education.

Still, there are also important continuities between the reforms of the neoliberal era and the more recent authoritarian turn. In what follows, I want to highlight a few that stood out to me during the research for a report I recently released with the Roosevelt Institute, which explores the neoliberalization of state governance of public university systems.

The neoliberal era of state higher education governance encouraged public colleges’ diversification of revenue streams, including by making them more dependent on funds provided by the federal government (via student debt and research grants) and wealthy donors. It also often shifted planning powers away from civil servants toward governors’ offices and (centrist or right-wing) think tanks.

As the report explains, these and other changes contributed to systems of public higher education in which well-endowed flagships, like Michigan, UT-Austin, or, my own employer, the University of Alabama, grow richer and serve mostly wealthy (often out-of-state) students, while regional universities and community colleges must make use of fewer resources to educate larger and poorer student bodies. Here, however, I focus on how these changes laid the foundation for both state- and federal-level authoritarian intervention. It is, as they say, one battle after another.

In the first three-quarters of the twentieth century, broad cross-class and cross-party support for state funding for public colleges made the enormous growth in college attendance possible. As a result, the fraction of 18- to 24-year-olds that went to college increased from 1% to 60%. Increasingly complex businesses needed educated workers, while newly mandatory high schools needed teachers. Local boosters saw growth opportunities, while progressive social movements saw opportunities for egalitarian social uplift. State governments pleased all of these constituencies by expanding their public colleges and managed growth by building relatively independent bureaucracies to develop multi-year plans (“state coordinating institutions”) and mechanisms for allocating fundings across institutions while leaving these institutions mostly to govern themselves.

The pro-higher-ed-growth coalition began to pull apart in the 1970s. “Tax revolts” against often regressive state funding schemes imposed new limits on state budgets. Backlash against racial integration and student protest made it easier to portray colleges as “out of touch.” And a new generation of policy intellectuals put forward arguments about the need to “reinvent government” to promote “efficiency” and “accountability.”

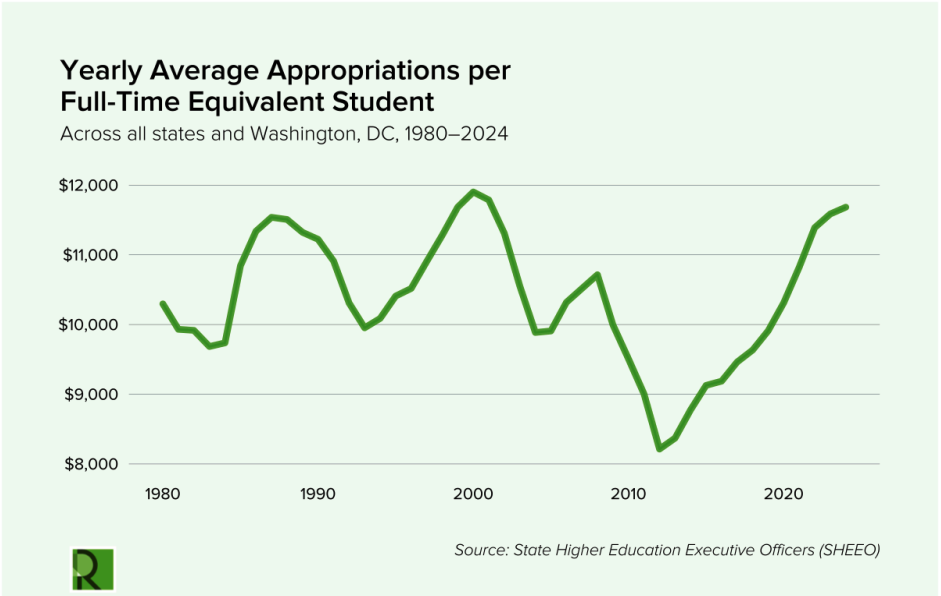

Contrary to what we often think (and what I once thought), the new politics of the neoliberal era did not lead to an overall decline in per-student funding for public colleges. In fact, even in inflation-adjusted terms, per-student funding in 2024 was actually higher than per-student funding in 1980. But funding did become much more volatile and came with more strings attached. With less budgetary flexibility (the result of prohibitions on raising taxes without supermajorities, balanced budget amendments, and the like), state governments began to use cuts to public colleges as a way to deal with shortfalls during downturns, restoring funding only once budgets were safely balanced again. And state governments began to make more funding contingent on colleges’ meeting various metrics of “performance” and/or to provide more funding through student grants rather than direct payment of operating expenses.

Instability in state funding encouraged colleges to diversify their revenue sources, most especially by raising tuition. In fact, when colleges discovered that easy access to student loans allowed them to raise tuition without facing reduced enrollment or immediate political backlash, it became easier for legislatures to balance state budgets on their backs. And, without such backlash, colleges saw no reason to lower tuition once funding was restored. Rather, they found other uses for the money (mostly hiring more administrators, paying top administrators and high-status faculty lavishly, and building new amenities). So tuition went up four times as fast as inflation between 1980 and 2023, raising student debt levels.

Increased reliance on debt-stabilized tuition had many consequences—some of which we have explored on this blog. But one consequence that has recently surged in salience is that it made public colleges (like their private counterparts) much more dependent on federal government spending. During the second Trump Administration, that dependence has been a major source of leverage for the authoritarian agenda. Ironically, the federal funding system was designed to avoid the possibility of exercising such leverage—and certainly for promoting ideological uniformity—precisely because conservatives had long been wary that the federal government might use this leverage to impose secular norms on religious schools, to compel racial integration on public institutions, and to replace open debate with politically correct censoriousness.

So it is not that the Trump Administration is showing that the shift from state to federal funding is itself a problem (state governments have used their own leverage in the past) nor that the system of federal student aid is especially vulnerable to authoritarian takeover. Rather, the Trump Administration has been looking for any leverage it can find that is even arguably built into existing law, and the growth of tuition-funding at public colleges provided some of that leverage.

A drive for “accountability” also led state governments to restructure their state coordinating institutions. Although changes looked very different across states, the overall trend, according to leading expert Aims McGuinness, “was that state coordinating entities continued to drift away from and lose relevance in the core state decision-making processes of the governor, the state budget office, and the legislative finance and appropriations committees.” Given its leadership role in speech policing, Florida is a notable example. It “dismantl[ed] its long-standing, powerful consolidated governing board” in favor of a multi-layered set of supervisory bodies, adding 100 additional political appointees to the system.

In light of the recent authoritarian turn, these efforts to promote “accountability” (efforts that were largely unsuccessful on their own terms) and to shift planning responsibilities to elected officials take on a different color. Governors’ offices became the central locus of priority-setting for state higher education systems, and both governors and legislators began to look to specialized think tanks (like Lumina or the Gates Foundation or ALEC) to expedite their planning processes. The initial focus of these offices was to make colleges more business-like, in the hope that doing so would make them less costly producers of human capital. But once right-wing political priorities turned toward indoctrination and stamping out political opposition, it was easier and quicker to implement this shift without independent bureaucrats standing in the way.

Finally, as explained in much more detail in the report, by pushing “market logic” into higher education, these reforms have made the rich richer and the poor poorer. More precisely, they have rewarded public colleges that act more like private colleges—competing across state boundaries for status and family wealth—while penalizing institutions that rely more heavily on subsidy to serve a broader portion of the population. When combined with the federal government’s increasing reliance on debt (over grants) to subsidize students, the net result was a system that shifted risk onto students, which reinforced inequalities between them.

It seems to me that this increasingly unequal system did a great deal of harm to higher education’s standing in our society, opening the door to right-wing attacks. People without college degrees have often found themselves left behind in the job market, and a growing number of people with degrees or who went to college without finishing have found themselves alienated and indebted. Meanwhile, elite public and private colleges gleam with wealth and prestige even as (ahem) many of the professors and students who attend them espouse left-wing ideas that many people do not encounter elsewhere. The same resentment that makes student debt cancellation popular makes it possible to mobilize people toward punishing colleges. And the focus of right-wing attacks has tended to be on precisely these well-endowed institutions.

These are just a few of the connections that can be drawn between neoliberal reforms in higher education and this post-neoliberal interregnum. Let us think of others. If we’re serious about contesting for what the reconstruction of higher education will look like after this moment, we will need to look more carefully at familiar institutions and revisit our analysis of them.