This post is part of a symposium on the political economy of technology. Read the entire series here.

***

In the prior two posts in this set I described how the leading mainstream economic explanation of rising inequality and its primary critique treat technology. The former takes technology as central, but offers too deterministic or naturalistic a conception of both technology and markets such that it functions, in effect, to legitimize the present pattern of rising inequality and to limit the institutional imagination of how to deal with it. The latter focuses so exclusively on the institutional determinants of bargaining power, that it largely ignores technology as a distraction. Here, what I’ll try to do is synthesize out of the work of many of us in the field an understanding of a political economy of technology that gives technology a meaningful role in the dynamic, but integrates it with institutions and ideology such that it becomes an appropriate site of struggle over the pattern of social relations, rather than either a distraction or a source of legitimation.

Technology (practical knowledge embedded in material culture; I’ll come back to this later) creates affordances and imposes constraints on what we can do practically, such that some ways of doing things are harder, and others easier. These affordances and constraints can affect patterns of production, participation, and reproduction in the main, while leaving substantial room for sustained divergence based on interaction with the institutional ecology of the society that develops and adopts the technology. Bartholomew Watson’s fascinating Barcode Empires underscores the extent to which introducing barcodes and optical readers gave large scale retailers sufficiently large advantages over smaller-scale grocers that retail chains grew dramatically across a wide range of diverse market societies. Nonetheless, the strategies and relations adopted by these new mega players and their workers and suppliers differed dramatically between the United States, where Walmart-style retailers squeezed both employees and suppliers; Denmark and Germany, where they shared the gains from economies of scale with workers and suppliers; and the UK and France, where workers shared in the gains but suppliers lost to vertical integration by retailers. This divergence was the result of the political coalitions that the emerging retailers had to form to deal not only with labor law, but also with local zoning and similarly pedestrian institutional constraints. Moving closer to the present, Dauth and collaborators have shown that despite the fact that Germany has seen higher robotics density in its automobile industry and other manufacturing than the U.S., it has not seen a decline in employment in these sectors. They attribute this divergence to the institutionally-mandated role of unions in German manufacturing.

Nonetheless, new hiring in German robotics-rich manufacturing has slowed, which means that the German institutions of are serving Polanyi’s double movement effect—delaying the shock for a generation to allow adaptation. More than merely slowing the pattern, however, the institutional difference may play a larger role in shaping the future trajectory of robotics. The German focus on “ cobots” or developing robots as complements rather than substitutes for human labor suggest a more foundational effect for the politics of technology. At any given moment, according to this version, technology has internal forces driving it, but there is a range of possible paths of development from any given point in the development trajectory. Institutions, politics, culture, will all drive development efforts toward leveraging one or another of these possible trajectories, and as investment in that direction deepens, path dependency makes paths not followed weaker, and harder to shift to after a while. In that case, strong German commitment to making automation complement a highly-protected labor force would lead to investments in complementarity-rich robots, while American commitment to high rent-extraction by managerial elites and shareholders, and Japanese aging and resistance to immigration, will direct those countries’ investments toward labor-displacing robots. One might imagine that Japanese leadership in robotics or American financial heft will win out; or that the vast global market of cheap labor whose productivity could be enhanced, and the difficulty of “the last mile of automation” would give the cobot-oriented path an advantage globally, not only in countries with powerful labor. Irrespective of predictions about who will win out in global markets for robotics, it is trivial to see that who wins will be a matter of great significance for the distribution of power and rents between capital and labor.

It would be a mistake, however, to imagine that only labor law, or only formal law in general, can interact with technology to shape patterns of social life, or that technology is purely the product of institutions, rather than coevolving with it. In 1966, Betty Friedan wrote in the founding statement of purpose of NOW that “Today’s technology has reduced most of the productive chores which women once performed in the home,” while it has also “virtually eliminated the quality of muscular strength as a criterion for filling most jobs.” Over time, scholarship has supported the proposition that diffusion of household appliances contributed to w ome n’s lab or force par t ic ipat ion , in particular married women, as Daniele Coen-Pirani and her collaborators showed. As Coen-Pirani et al showed, this diffusion occurred primarily in the 1960s and 1970s, at the same time that the Equal Pay Act, Title VII, and later Title IX struck down formal barriers to women’s workplace participation and education, while the pill, no-fault divorce laws, Griswold and ultimately Roe v. Wade transformed the realm of reproduction—the primary site of women’s subordination for, more or less, ever. But again, to imagine that the primary transformation of the 1960s and 1970s surrounding gender relations was a collection of home appliances and discrete legal rules, rather than a fundamental battle over ideas about women and men, sex, the family, the relationship between “person,” “mother,” and “wife”; all this would be to miss most of what mattered. Equally important was that, as Kathleen Thelen showed in Varieties of Liberalization, the interaction between how societies dealt with the collapse of the “Golden Age of Capitalism” and the rise of global competition, on the one hand, and the responses to the women’s movement (including the transformation of women’s participation in the workforce), on the other, played a central role in the divergences in patterns of liberalization between the Nordic social democracies, the mainline European social democracies, particularly Germany, and the United States.

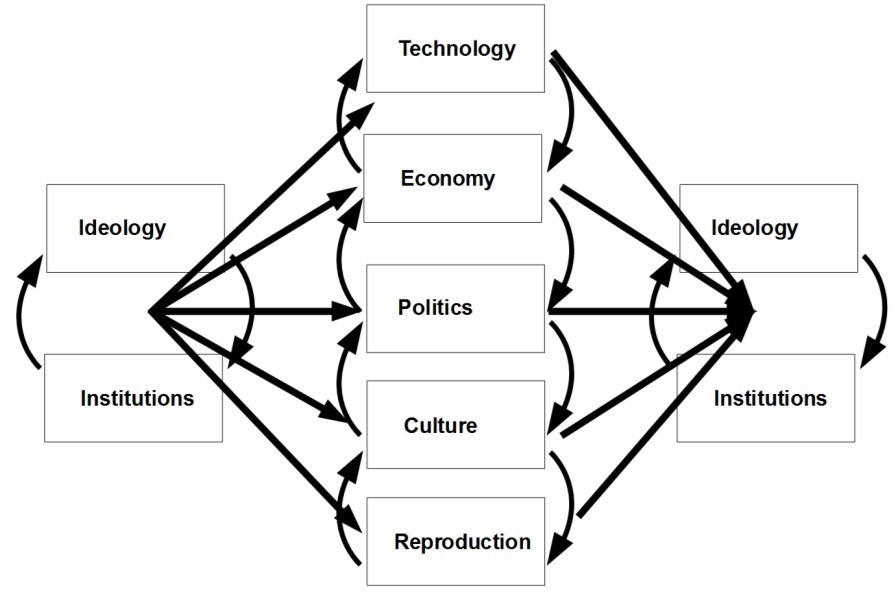

The model that comes out of these observations offers technology more of a distinct role in the organization of social relations, without making it either wholly exogenous or peripheral.

Institutions and ideology interact to shape how technology, the economy, polity, and the biological and cultural reproduction systems function. By “institutions” I mean to capture law and norms, as already widely used in legal academia, but also organizational routines (“managerial culture”), unthinking habits of practice in social relations and so forth. By “ideology” I mean to capture the elusive but persistent idea in the work of many, be it Goffman’s “frame”, Bordieu’s habitus, Gramsci’s hegemony, Lukes’s third dimension of power (with all the important differences among them), that how we understand the world, how we “know” what causes what, what goes with what, what is or is not valued, all these form a mental frame without which we cannot understand or value the world around us, and that is itself a site of struggle over the power to shape these understandings.

Nowhere has this fact been clearer in the recent past than the victory of the gay rights movement in the realm of ideas, and what counts as “love” as opposed to “obscenity,” well before it won in the realm of formal institutions. I tried to show how, for example, the rise of winner-take-all ideology preceded and contributed causally to the rise of the 1%, independently from the dramatic institutional changes that made that great extraction possible.

By “technology” I mean (a product of many email exchanges with Talha Syed, and still all errors are mine) congealed practical knowledge embedded in material culture. By focusing on “material culture,” I am trying to emphasize the distinction between technology and ideas or knowledge. For example, finance theory changed dramatically from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, but it was only when the personal computer and spreadsheet were introduced in the early 1980s that these already-worked-out ideas could turn into social practice in the economy. It was only then that collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) or leveraged buyouts could be calculated, and hence executed. And these, in turn, transformed the American economy in combination with all the institutional and ideological changes necessary to drive the rise of financialization. It is that materiality that gives technology its stickiness; its capacity to make some things actually easier or harder at a given time, in the short to mid-term that determines what and how we do now.

I say “congealed” to capture a mid-state between technological determinism and complete social determination of the content of technology. The idea is that technology is responsive to institutions and ideology, and co-evolves with markets, politics, and culture over the middle-to-long term, but offers real constraints and affordances in the short-to-middle term. It really is an outcome of prior choices, struggles, and decisions, and can be designed to be otherwise—and thus is plastic over time—but it does in fact make some things easier to do and others harder to do in the here and now, and therefore shapes patterns of behavior at a societal scale and imposes path dependent patterns that differentiate between different societies depending on the particular patterns of technology and its uses they adopt. And it is precisely because we believe that technology does have a real impact on behavior in the short term, but is subject to shaping and design in the mid to long term, that the politics of technology can be so fierce.

This interaction shapes the social relations that make up the economy, polity, kinship, and culture, as well as the social relations surrounding the use and development of technology.

These domains shape each other, borrowing, forcing change driving adaptations from one subsystem to the next, push back on the institutions and the ideology, until they more or less stabilize for a time, until the next shock or one or another of the systems opens up opportunities or needs for restructuring. That’s what in Wealth of Networks I thought the introduction of the Internet did; and that’s what I think the Great Recession and after it the Occupy movement have done to the regime of pluralist oligarchy that has governed the United States, the UK, and to varying degrees of lesser extent many other members of the club of wealthiest countries since the 1980s.

The Great Recession fundamentally destabilized the oligarchic, globalized, but pluralist and cosmopolitan political settlement that came to fruition in the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century. The most politically successful countermovement has rejected both globalization and pluralism—the economic nationalism of Trumpism, Brexit, Salvini, Le Pen, and the Austrian Freedom Party and AfD at the heart of democratic societies, and the rise of illiberal majoritarianism on the newly-democratized peripheries—Hungary, Poland, Turkey, and the Philippines most visibly.

The American left’s rediscovery of socialism (just as the SPD and the French socialists are struggling with irrelevance), whether in the white-haired nostalgic version of Bernie’s “I’ve come to look for America” or the vibrant youth of Ocasio-Cortez, seems, at the moment, to be driven by an urgent desire to dream bigger and to reassert the centrality of economic inequality to the left’s program and insisting that doing so can only be done by equally insisting on the core commitments to antisubordination: primarily based on race, gender, and sexual orientation. But it does not have a coherent theory—old or new—of what is wrong with capitalism or a programmatic framework to replace it.

Don’t get me wrong. I think embracing an ambition for systematic change is critical, and a welcome change from decades of supine acceptance of the neoliberals’ power to frame the bounds of the possible as far as economic relations are concerned. But the DSA’s strategy document is littered with old-fashioned ideas like nationalization of not only utilities and housing, but “strategic industries (banking, auto, etc.).” It calls for public investment in new technologies based on the public good, primarily energy renewability and sustainability, but assumes that these will deliver increasing efficiencies in labor productivity that will permit us to shorten the work week. How technology interacts with any of these radical transformations of economic organization is left unstated; and no one knows. If any of these are to approach plausibility, we need a serious effort to understand how the social relations that define the economy and the polity interact with the technological development. In the broader progressive awakening, current debates over UBI vs. a universal jobs guarantee are mostly fought out on the policy details of one or the other, rather than conceived and evaluated based on a broader conception of what went wrong and how one or another intervention will transform the system generally. Proponents of UBI have increasingly taken the shortcut of buying into the deterministic effect of robots on structural unemployment; while advocates of universal jobs guarantee largely ignore the limitations of state-based solutions subject to the known failure modes of bureaucracy and politics.

In the meantime, the most intensive efforts to promote and experiment with practical post-capitalist alternatives are coming from those on the left who are intensely focused on technology. Efforts that came out of the Free Culture movement were primary elements of Podemos, and have combined with other social activists to form the Barcelona en Comu party at the municipal level—perhaps the most comprehensive government-backed effort to create a social and solidarity economy that is distinctly different from capitalism as we know it. Other, less-political-system-oriented efforts include the increasing interest in platform cooperativism, open cooperativism, and more ethical business-entrepreneurial focused efforts like OuiShare. These efforts open initial avenues to developing a transition plan from discrete cooperativist models, even if done with municipal participation, to a national-scale political program. We are still quite far from developing a coherent alternative to the ascendant economic nationalism, on the one hand, or the resilient techno-libertarianism of Silicon Valley, on the other. Developing a coherent, systemic understanding of what brought us to the present crisis, and building from that understanding a coherent programmatic response is what I take to be the most important task of the effort to revive political economy as a field. Combining the ambition of a national, systemic-scale transformation, rather than ameliorative politics, that the re-embrace of “socialism” seems to mark as the new goal of the American left, with the experimental, commons-oriented and cooperative practices that have emerged out of the networked environment seems to me one of the most promising avenues to pursue. Harnessing that intensive experimentation and practical utopianism of online communities, and avoiding the twin errors of treating technology as an exogenous force or as strictly dominated by institutional factors is the biggest payoff of the effort to integrate technology and law into the field of political economy. Only if we understand how institutions and ideology shape and interact with the economy, polity, and technology can we develop such a coherent program; and only such a coherent program can be broad and systematic enough to change the course of the economy that neoliberals have built for us in the past forty years.